Several times in the past few weeks, I have posted here about the notion of kinship. I posted my comments on the “kindom” of God made at the DOC General Assembly, a review of Paul’s relationship with his own kindred Israel, and earlier, a discussion of one of the “kingdom parables.” The idea of kinship permeates the biblical text, and it’s a huge part of the Christian vocabulary of faith. For example, early Christians sometimes roused suspicion from neighbors when they called each other “brother” and “sister” and greeted each other with a kiss, leading to accusations of improper family relationships. Those people were not literally siblings, but instead engaging in what sociologists sometimes call “fictive kinship,” creating chosen family bonds with each other…and in any event, the kisses of greeting seem to have been perfectly chaste.

But kinship (and its vocabularies) are not neutral or inert things. They come with a host of associations for different people, not all of which are positive. For instance, in the paragraph above, I at first used a word that’s specifically for improper family relationships, but then took it out for fear of surprising a reader with that word when they weren’t expecting it. Kinship is not always life-giving. Family relationships can be a tremendous source of pain and suffering, as we all know from experience or from the experiences of others, and even in the best of times, being a part of a family can be a complicated thing. The biblical text does not ignore that fact; if anything, the bible leans into the difficulty of being part of a kinship system.

The lectionary has been following the part of Genesis that is devoted to the family history of Abraham and Sarah and their descendants—sometimes called the “patriarchal history” in the past, and now sometimes just called “the family history” or “the history of Israel,” to distinguish it from the early parts of Genesis which focus more on general world events (like Babel and Cain and Abel). Genesis, in turn, follows this family, from Abraham to Isaac to Jacob. This week, we pick up the story of one of Jacob’s sons, Joseph, and we dive right into some intense family drama. By now Jacob is known as Israel, and the text says that “Israel loved Joseph more than any other of his children, because he was the son of his old age.” That’s already a recipe for conflict, and the text reports that indeed, Joseph had gotten on the wrong side of some of his brothers.

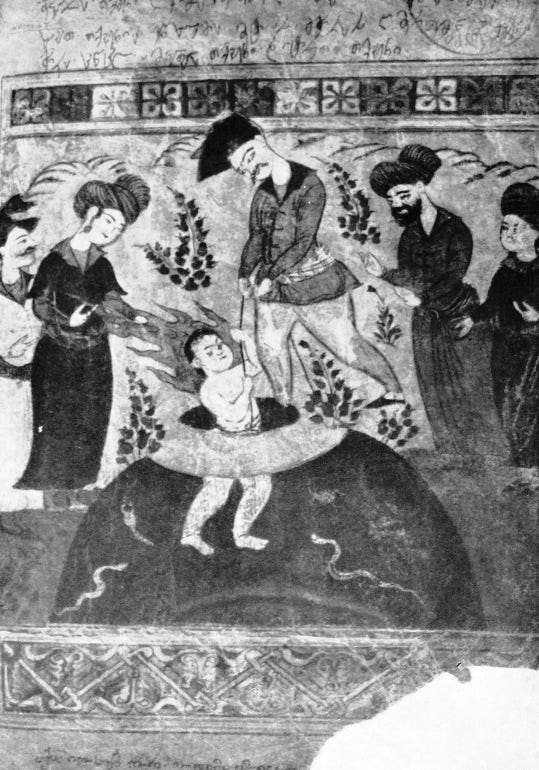

Conflict happens in every family, but this family really went all-in. Joseph’s brothers first “conspired to kill him,” which is a pretty dramatic thing to do. But then they thought better of it; having trapped him in a pit, they sold him to some Ishmaelites who were on their way to Egypt. This is a symbolically rich moment; the Ishmaelites were by origin story the distant cousins of Joseph and his brothers, the descendants of Abraham’s son Ishmael. The brothers essentially sold Joseph out of one side of the family, and into the hands of a rival branch. (In reality, these kinds of branches in families tend to be more interconnected than not, and in any case the origin stories found in the bible don’t necessarily give us genealogical data—they are simply telling a good story that explains something about the world). Joseph, therefore, makes his way into Egypt not as a free person but as an enslaved person, the first of many Israelites to be enslaved in that place.

It’s a powerful thing that the biblical tradition talks about kinship this way. Think about some of the formative texts or media that influenced your ideas about family. Maybe it was a children’s book, with descriptions of a mother bear, a father bear, and a baby bear. Maybe it was a fantasy novel that hinged on a mysteriously or tragically absent parent. Or it might have been a sitcom with two parents and two kids. We get a lot of messages subconsciously about what a family is or ought to be, and we end up comparing those messages to our own reality, and developing feelings of self-worth based on that comparison. The bible has played that role for millennia; it has given us models for what a family might look like, and rarely do those models look perfect. This is why you should be very suspicious of anyone claiming anything about “biblical family values;” that is such a vast and useless category that anyone using the term is almost guaranteed to not know what they are talking about.

Far from presenting ideal models of family life, the bible gives us example after example of how it can go wrong. Already by this point in Genesis (chapter 37), we have seen one sibling murder another, a husband pretend that his wife is his sister so that she is taken into the pharaoh’s harem, a brother trick another out of his inheritance, an uncle trick his nephew into marrying two of his daughters instead of one (plus two other enslaved women as well), and now brothers selling another brother into slavery. It’s hard to square any of that with “biblical family values,” but it’s even harder to hold much of it up as an example of how to live. Instead, I think we are supposed to understand these passages not as moral exemplars, but as stories to be held up alongside our own experiences as a way to understand the way kinship works in the real world. Brothers hate each other, parents do the wrong thing, people suffer abuse, and sometimes things get sacrificed in the name of tradition. The bible isn’t sanctioning any of that, but it is giving it to us as a set of stories to help guide us through our own experiences with kinship and belonging.

The story of Joseph does not end in tragedy, but most stories like it do. That’s what’s at stake in this story, and the reason it makes for compelling narrative: Joseph is in real danger, brought on by his own family. That’s a familiar story to a lot of people, and I find it remarkable that it’s part of a sacred text. That presence in the text—that representation, if you will—has not put a stop to the kinds of suffering that can come from families. But perhaps it has given us a tool to talk about it.

Eric, excellent post. I particularly like your description of the text as a mirror, however, I think.it is also a window, too, but sometimes we do not see clearly (as in a glass darkly).

Also, I second your suggestion for "Warmth of Other Suns". It was an eye opener for me too.