Since I started this Substack about a year ago, one of the things that a lot of people have said to me is that they enjoy reading my lectionary reflections, but they don’t really belong to a tradition that uses the lectionary or have a habit of following it. I definitely understand that; before I went to seminary over twenty years ago, I had never heard the lectionary, and I had attended a lot of churches that didn’t use it. I have come to really enjoy the lectionary as a kind of disciplinary guardrail; it presents texts to me that I would not ordinarily consider or even notice. It also makes me think a lot about the canon-within-a-canon aspects of the bible; the lectionary makes choices from within the bible and leaves other things on the cutting room floor, but so does every other process of selecting texts from the larger biblical corpus. Even if you’re just “following the Spirit,” or preaching thematically, or working through the bible start to finish, you’re still engaging in a process of choice, which is itself an act of interpretation. The lectionary takes some of that choice out of your hands, but it presents other choices to you, about which text(s) to read, and about how to interpret them.

In the lectionary for August 6th, I wonder how that process of choosing will play out. There are some absolutely iconic texts in this week’s readings. The version of the feeding of the 5000 from Matthew is the gospel reading, and there is undoubtedly a lot to say about that passage. The Genesis account of Jacob’s wrestling with the man/angel/deity is in there, and that’s a haunting and beautiful story. Even the reading from Isaiah is pretty compelling. Faced with the whole of the biblical text to choose from, it’s easy to imagine folks picking one of those three texts to read and interpret, and faced with a single set of lectionary readings that includes all three, they will present tough either-or challenges to a lot of folks.

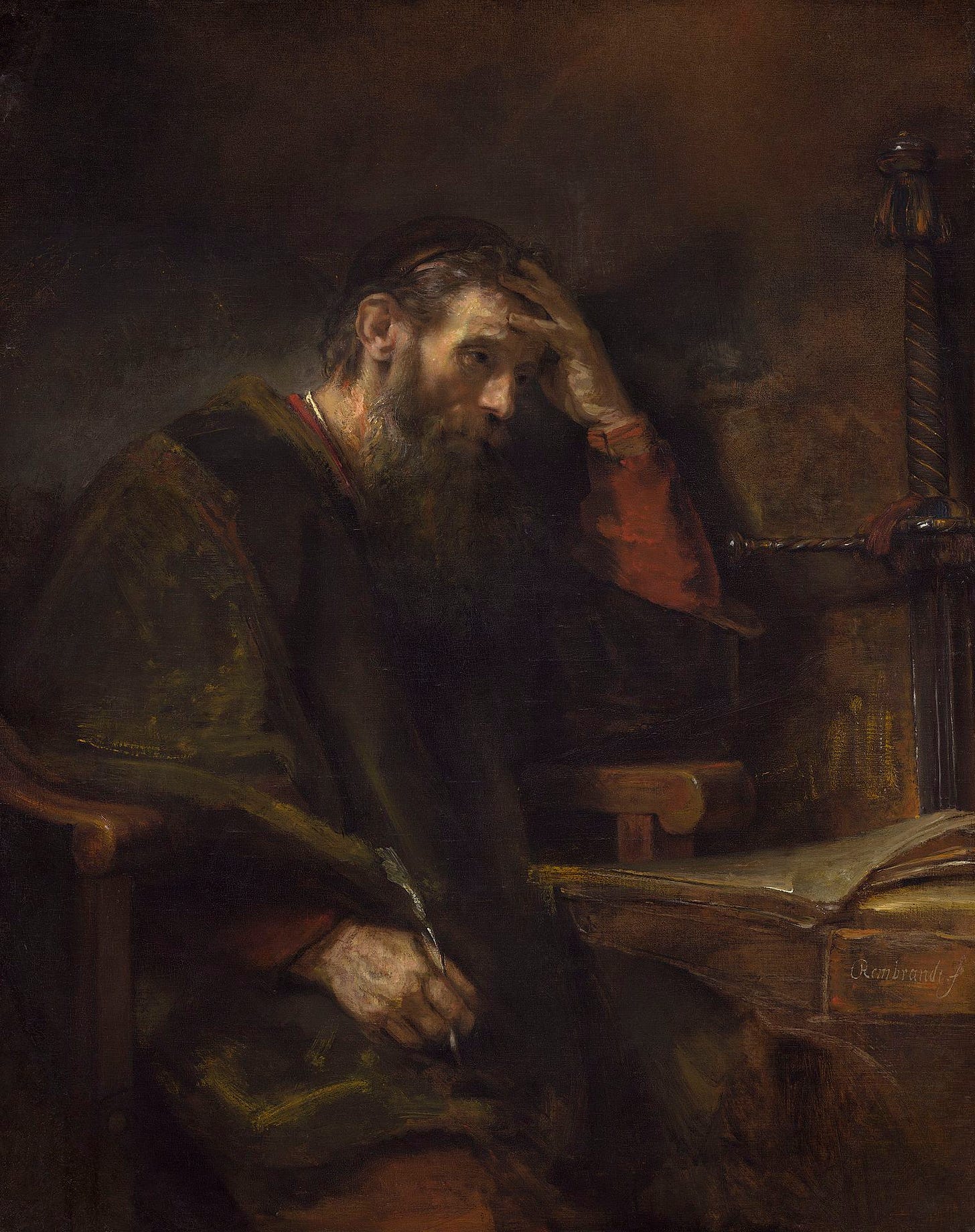

But the one that caught my eye is Romans 9:1-5. The epistle reading often feels like the odd one out in the lectionary—at least to me. Maybe this is because epistles tend to be didactic and flat, rather than the kinds of rich and rounded stories that you see in the gospels and in the Torah. They are excerpts from letters, after all—not the kinds of literature that often produce great tales. But—and here’s what I’m driving at—the epistles are also one of the great powerhouses of Christian theology, especially Protestant theology, and especially especially the Calvinist variety. So much has been squeezed out of Paul’s letters over the years that a lot of what counts as Christianity, in many streams of the tradition, comes from there. (I wrote a whole book about it, which you can buy here with special discount code GA2023 that will get you 20% off through August 4th). So, while I personally don’t think I would choose this Romans passage to preach about from this week’s lectionary, and I certainly wouldn’t pluck it out of the whole bible if I weren’t following the lectionary, I’m very aware that for many people Romans is the heart of hearts of the biblical text. In many churches, it’s common to preach from Paul as often as from the gospels, spinning the epistles’ challenges and commands into exhortations to salvation and ethical living. So a book like Romans has immense power in certain parts of Christianity, and a passage like this one—Romans 9:1-5–is an outsized presence in the canon and in the canons-within-the-canon that we all know and use.

If you buy that book that’s linked in the last paragraph, you’ll see me following an argument set forth by scholars of Paul that the purpose of his letter to the Romans was not, as many have assumed, salvation. These days it’s common for Christians to think that Paul was writing Romans as a kind of theological tract, a “gospel according to Paul,” to lay out how salvation works. There’s even a “Romans Road” to salvation, created by taking quotes from the letter out of context and out of order, that is designed to help lead people to accept Jesus as a savior. But most scholars of Paul these days don’t think that’s what Romans was meant to do at all. Many (and I’m among them) think that Romans was a kind of missionary letter, but not in the sense that modern evangelicals think it was. Romans, instead, was a letter written by Paul as an extension and arm of his own missionary work, meant to garner support for the next phase of his mission, which was to Spain. (Take a look at chapter 15 of Romans, which outlines the ways Paul thinks he is finished working in the east, and ready to move to the west and to Spain). To do this work, Paul needs moral support and financial resources, and he writes Romans to ask the churches there for both of those things. He needs their help, as a way station west, to fuel him up and send him onward to where he thinks God is calling him.

But Paul has a problem, which is that he doesn’t know the Roman Jesus-followers. The rest of his letters are written to churches he knew—ones that he had founded and visited. But the churches in Rome were founded by someone else (we don’t know who) and operated outside of Paul’s network. He needed to introduce himself to them, and more than that, he needs to disabuse them of some of the things they have heard about him. To further complicate things, it seems that the churches in Rome were fairly diverse, as might be expected from such a large and cosmopolitan city—a million or more people strong around Paul’s time, absolutely enormous for that day, and populated by people from all over Europe, Africa, and west Asia. Specifically, there are a lot of indications in Romans that Paul knew of a particularly sticky issue in Roman Christianity, which was that both Jews and gentiles were side-by-side in the churches there. A lot of his letter to the Romans dwells on this problem—how Jews and gentiles should get along, what conflicts might divide them, and how gentiles can legitimately be a part of a Jewish tradition like Christianity. It’s likely that Paul was addressing these things in the letter because he knew they were a difficult problem in Rome, but also because he himself had a reputation as someone who played fast and loose with his own Jewish identity. Romans sometimes reads like someone tiptoeing through a theological and ethical minefield, trying to avoid the explosives, which is pretty close to what he was doing, especially in chapters 9-11. He needed their support, after all, so he needed them to trust him or at least to believe in his mission. And he didn’t need to blow anything up along the way.

9:1-5 comes at the beginning of the most tortured stretch of this argument, and this passage kicks off a longer discussion that circles around this question of Jews and gentiles. As I have written elsewhere, following the great Paul scholar Kristen Stendahl, sometimes the way to understand what Paul is trying to see where he thinks he has ended up at the end of an argument. Paul has a way of being obtuse, repeating himself and hinting at things rather than saying them outright. But usually he ends up somewhere, and you can trace backward from there to see where he thinks he has been. In the case of Romans 9, this passage leads directly into an affirmation of Abraham’s calling and promise, and to the durability of the people of Israel. So that has to be an interpretive key for this beginning part of chapter 9.

I say all of that because a lot of folks have read this passage and other ones from Romans and elsewhere in Paul’s letters, over the years, as a rejection of Israel and Paul’s rejection of his own Judaism and Jewish identity. This is, I think, exactly wrong. Here, Paul is not rejecting Israel but affirming it. He’s saying, in essence, “yes, I am stuck between my Jewish identity and my conviction that God has reached out to gentiles, but even so, I cannot abandon my people.” “I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my own people, my kindred according to the flesh,” he writes in 9:3. But then he goes on to affirm Israel in the strongest terms. “They are Israelites, and to them belong the adoption, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship, and the promises; to them belong the patriarchs, and from them, according to the flesh, comes the Messiah, who is over all, God blessed forever.” It’s hard to imagine a more forceful endorsement of the role of Jews and Judaism in God’s plans than this; this is Paul trying very hard to put to rest any suggestion that gentiles would be replacing Jews as God’s people.

It’s important to be clear about this, because the subsequent history of Christianity gets this very wrong. Christianity has, in fact, claimed to be the true Israel, a replacement for Abraham and Moses and Jews and Judaism. It has gone on to denigrate and persecute Judaism for centuries, beginning in the first century and continuing to the present day. Christianity, in many times and places, has built its self-understanding around the replacement of Jews. And they have often done it with bad readings of Paul, reading him exactly wrong to say that Jews were no longer God’s people.

So, when I see this passage pop up in the lectionary, it gives me pause, because I am sure that it will be proclaimed and preached in this wrong way. And even for those who don’t read the lectionary or use it, this passage has a way of making its way into Christian theologies (and especially Protestant ones) in really harmful ways. It’s incumbent upon those of us who belong to these histories and traditions to resist and counteract this historical tendency. We have to the be the ones who point out how harmful it has been, and to offer up a reading of Paul (and indeed the whole New Testament) that protects Jews and Judaism, and honors them as the “kindred” of not only Paul but also Jesus and nearly every other person we meet in the New Testament. For too long, Christianity has premised itself on anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism and the violence that came with them, and in our own generation, we must begin to do it differently.