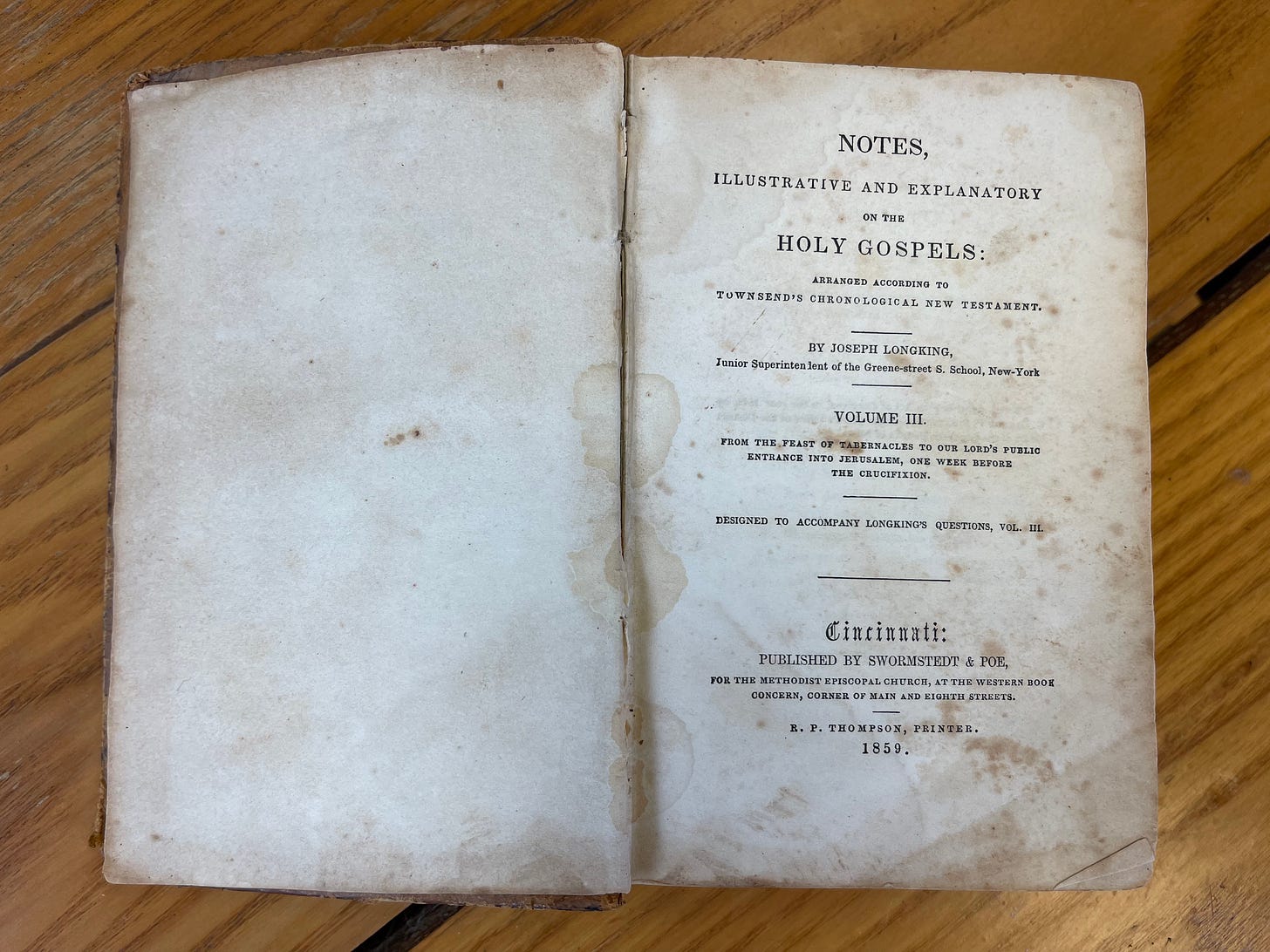

Some of you might remember my post of a couple of weeks ago about an old book I have my office. I have some updates on that post! My colleague Rev. Dr. Cathie Kelsey, who is an expert in many things including the history of Methodism and Wesleyan movements, sent me a lovely email with some gentle corrections and additional information. I thought I would pass along some of her thoughts, with her permission.

One thing she clarified for me was that the publisher listed—Swormstedt & Poe—is actually the names of the Methodist Book Concern’s co-editors. “The Methodist Book Concern published its books under the names of the co-editors of the Concern,” she wrote. “Those persons changed out every four years (or so). Thus, different editions of the same work might be published under different names because the editors of the Book Concern had changed in the interim.” That’s super interesting, in part because the first editor listed in this book, Swormstedt, is also a party to the Supreme Court case.

Dr. Kelsey also pointed out that this book would have functioned like an adult Sunday School curriculum, setting a kind of common course of study for use by class leaders to teach groups of students. Usually, she says, this leader was a lay person, which makes the book itself all the more important as a matter of disseminating ideas. Dr. Kelsey found it “interesting that Longking was using Townsend and not using John Wesley's Explanatory Notes on the New Testament - which have had doctrinal status for Methodists since 1808, and still do today.” It’s not totally clear what or who this “Townsend” is, but part of me wants to track it down and see if I can figure out what was at stake in that choice. Did it have something to do with the political and religious moment, in the mid-19th century? Dr. Kelsey followed up in another email with some more context: “The bible was NOT neutral to Methodists at that time…That's why it was important for there to be a Book Concern and separate curriculum from the Sunday School Union (which was dominated by "Calvinist" interpretations of the bible).” So, in some ways this little book was doing some theological work to keep folks on what its authors and publishers understood to be the right side of a theological and interpretive divide. “Methodists were adamant about reading "scripture" to tell a narrative in which grace in Jesus Christ was offered to ALL people, not just to the elect,” she wrote. “Our contemporary "all means all" phrase has its antecedents in that interpretive view. And Methodists published a great deal of argumentative literature on that point in the 18th and 19th centuries.” This is fascinating to me!

One of the important splits within Methodism in the 19th century (that endures to this day) was along racial lines. Dr. Kelsey sheds some light on this. “African American Methodists were adamant about reading scripture as a liberative text that stood over and against not just slavery but also against white privilege. Obviously, white Methodists were not, for the most part, in agreement with this view. Even abolitionists tended to hold white superiority as an obvious ‘given.’" So far this is disappointing, but not surprising. But in a way that shows how much praxis and interpretation matter, Dr. Kelsey continues. “But AME and AMEZ and later CME accounts of their history start, not with John Wesley, but with African Americans choosing the Methodist theology as most adequate in their pursuit of following Jesus, and Methodist polity most congenial for organizing and growing the church. The liberative reading of scripture is as old as the first Methodist preaching in America, particularly among African Americans.” I find this point to be in a lot of agreement with the arguments of one of my favorite recent books, The Genesis of Liberation: Biblical Interpretation in the Antebellum Narratives of the Enslaved by Robert Sadler and Emerson Powery. The practice of interpretation was both constructive and subversive, and Dr. Kelsey is pointing out how that practice was happening not only for biblical interpretation but also on the level of theologies and movements.

Finally, Dr. Kelsey reflects on the court case. She offers some “background on the civil suit that went to the Supreme Court: in the 1844 agreement to divide into MEC and MEC, the South agreed to split the Book Concern. But when the MEC (north) met in 1848, they decided unilaterally that the MECS had left the MEC and that the 1848 General Conference could make a different decision about the Book Concern. Since almost all of the Book Concerns assets were tangible (printing presses, building, previously printed materials), they were quite difficult to liquify in order to make a cash payout to the MECS. I suspect that (and vengeance) contributed to the decision. Functionally, the Book Concern was the pension program for widows of clergy and "worn out" clergy. So the decision meant that southern widows and retirees were left without financial support.” I’m struck by the parallels to conversations happening in the United Methodist Church today about pensions, property, and the cohesion of various associations of Methodists. I don’t pretend to be a Methodist, but it seems like we’ve been down this road before, at least a little ways.

I’m really grateful to Dr. Kelsey for sharing her knowledge and wisdom with me, and allowing me to share it with you. If you want to experience more of her knowledge, on a somewhat different subject, check out the magisterial translation and critical edition of Friedrich Schleiermacher’s Christian Faith, which she published with her late husband Terry Tice about six years ago.