Every spring (before the pandemic), the school where I work held a book sale. People are forever donating books to theological libraries, but most of the time those libraries don’t have need for the kinds of books that come through those sorts of donations. Iliff’s solution to this problem is that once the librarians have gone through the donations to pull out anything that could be added to the collection, the remainder are donated to the Student Senate, which collects them and holds the book sale as a fundraiser. The book sale sees thousands of books, loosely categorized into subject areas, arrayed on long tables. If you go on the last day of the sale, you can fill a box or a bag with whatever you want for a couple of bucks.

A half a dozen years ago or so, I was shopping this book sale when my eyes rested on an especially old-looking book. I am not an expert on antique books, but I do think they are cool, so I picked this one up and added it to my box. I bought it alongside a bunch of other stuff and took it back to my office. Once I was there, I opened it up and began to see what it was all about.

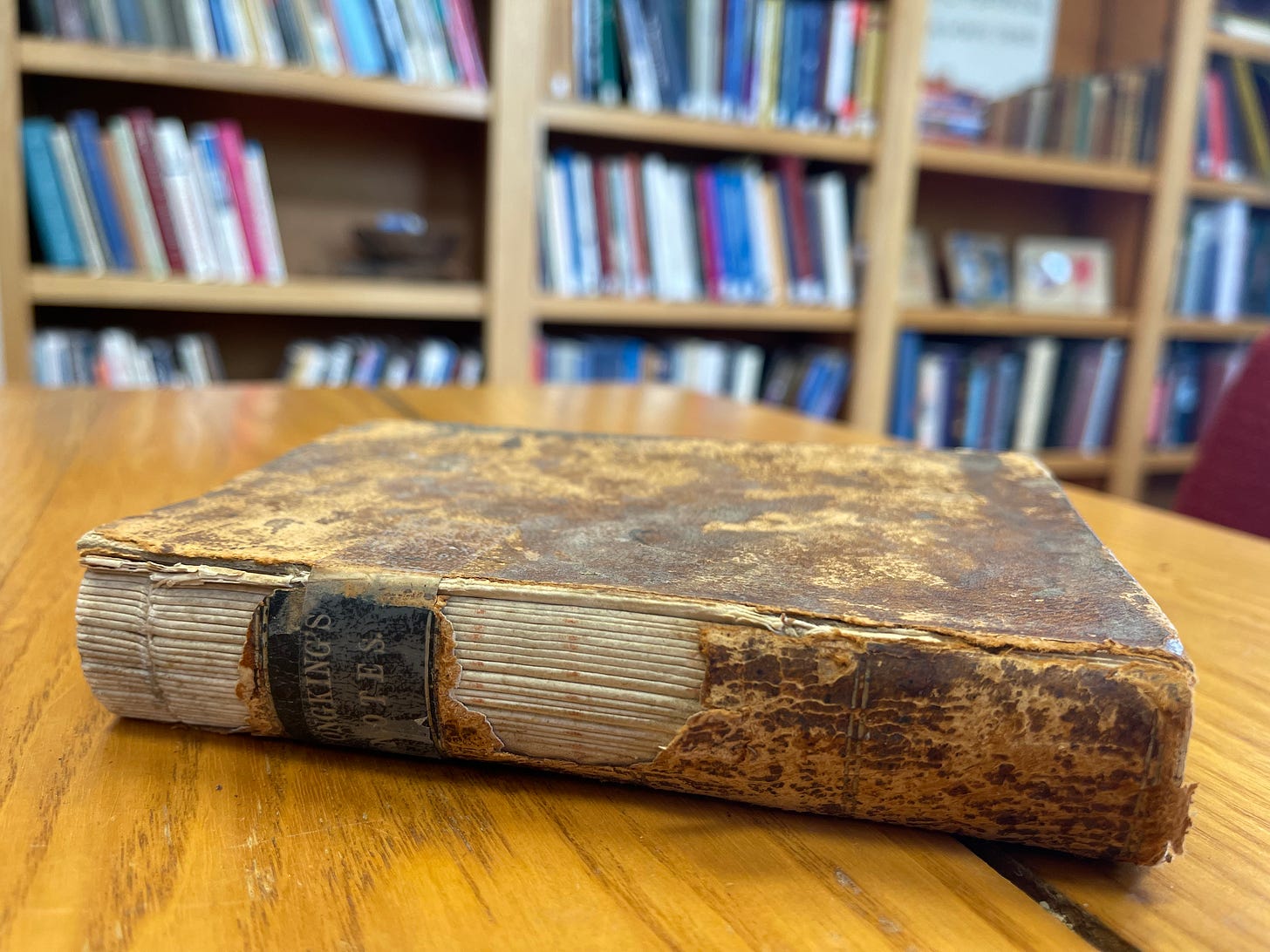

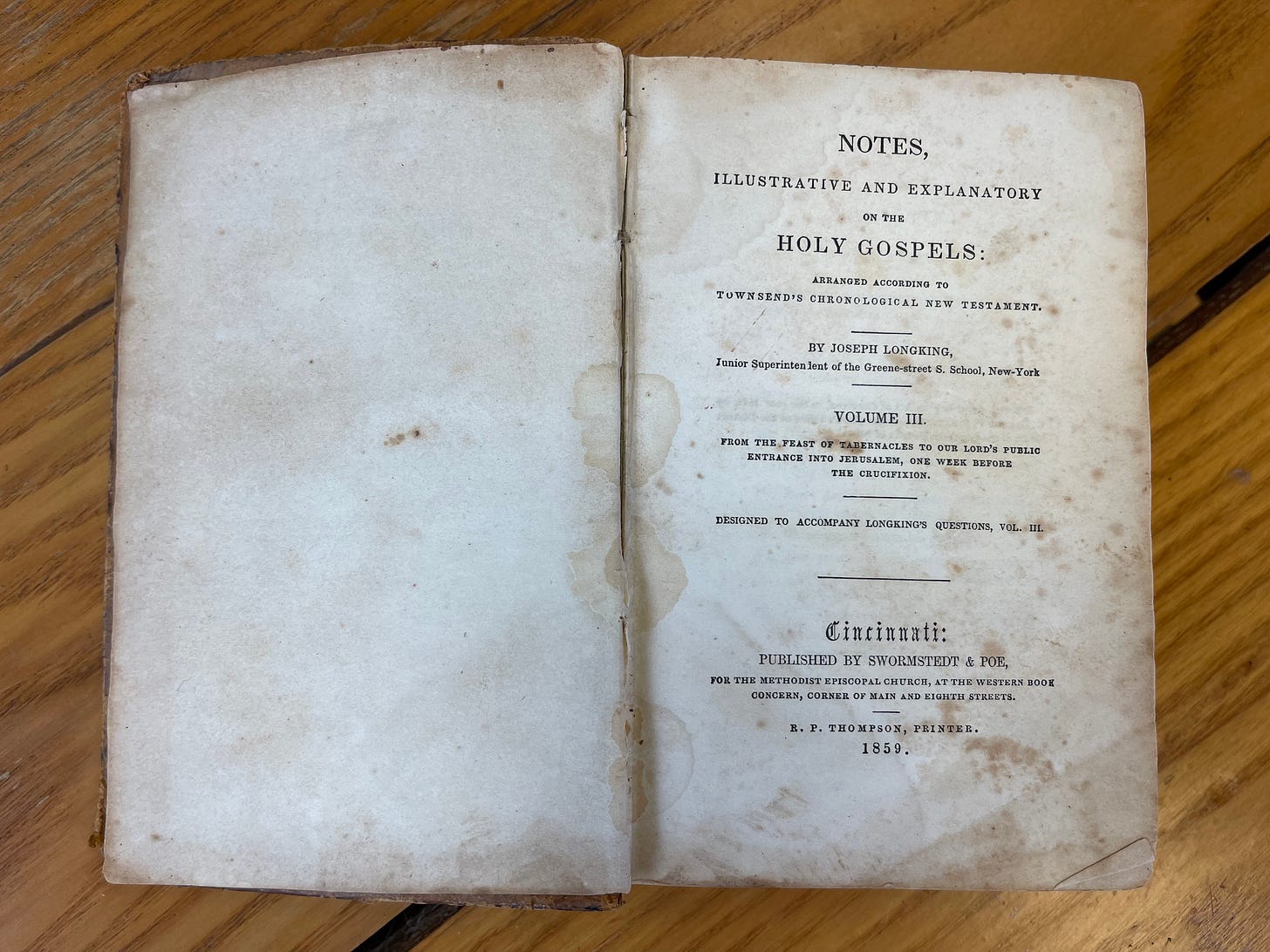

It turned out to be a copy of a book titled Notes Illustrative and Explanatory on the Holy Gospels by Joseph Longking—the third volume, which follows the gospel texts “from the feast of the tabernacles to our Lord’s public entrance into Jerusalem, one week before the crucifixion.” It had been published in 1859 in Cincinnati by Swormstedt & Poe. Swormstedt (also known as and related to the “Book Concern” and an associated fund) was a publisher that specialized in Methodist books, such as hymnals and sermons. More on that in a moment. The book itself was in pretty rough shape, its cover worn out and flaking away, and many of its pages stained. When I opened it up, though, I found something completely unexpected: scrawled handwriting, done in pencil, across the inside of the front cover.

To this day, I can’t read all of what is written there. It is faded in places, and the script isn’t one that I can always make out. But part of it is especially legible, written in bolder pencil than the rest: “Confiscated from the Rebels by the yankies in 1863 April the 30.” This is a striking inscription, and for me it crystallizes some of the biggest questions about the place of religion within American history and culture.

I have gone looking for any Civil War battles that took place on or around April 30th 1863. There were a few skirmishes here and there, but nothing that jumps out as overwhelmingly likely to have given any “yankies” the opportunity to confiscate a book from the “Rebels.” I am no historian of the period, but it seems just as likely to me that this book could have been taken off a dead soldier along the way, gathered up as part of the belongings of someone being held as prisoner, or removed from a home or other building as an army moved through the South. Unable to read the rest of the inscriptions (aside from a word here or there) or to link the “M. E SS” of the inscription (which I take to have been the initials of the book’s first owner), I don’t have a lot to go on. Perhaps this post will find its way to an epigrapher, bibliophile, or historian who will have more expertise and knowledge than me, who can help me think about what its story might hold.

The truism expressed by Abraham Lincoln in his second inaugural address, that both sides of the Civil War “read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other,” is certainly evident in this book. A book of notes on the gospels was as useful to one side as it was to the other, which explains some of the reason it was taken from one side by the other. Christianity was, of course, practiced by the combatants of both the South and the North, notwithstanding Harriet Jacobs’ observation that “there is a great difference between Christianity and religion at the South,” by which she meant that a slaveholding religion could have no legitimate relationship to Christianity itself. Frederick Douglass famously seconded this notion, saying that “to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked.” Slaveholding religion had nothing to do with Christianity, they both claimed.

As much as I admire the sentiment and understand the circumstances in which they expressed it, I think I have to disagree. Christianity has engaged in plenty of slaveholding in its twenty centuries, and it is important to acknowledge that, and to own it as part of history. While we might see an irreconcilable difference between slavery and Christianity, many others did not, and we shouldn’t lose sight of the ways religion has been (and continues to be) pointed toward immoral, violent, and corrupting purposes. Rather than excising or exorcising the worst from Christianity and declaring that it never authentically belonged, better to accept the corrupted whole and try to understand what it is about the tradition that authorized (and authorizes) deep prejudice and moral evil.

As it turns out, a half a dozen years before Longking’s book was published, the publisher Swormstedt & Poe had been party to a Supreme Court case that brings this into relief. In the lead-up to the Civil War, many Protestant denominations in the United States were torn by conflict over abolition. These religious conflicts mirrored the geography of political conflicts. Northern parts of denominations tended to favor or at least tolerate abolitionist movements, while southern parts preferred to defend the practice of slavery as integral to or compatible with the practice of Christianity. Many denominations today were spun off in the 1840s and 1850s as either southern or northern factions of a predecessor denomination. Among the schisms of this period was one within the Methodist Episcopal Church, which saw a Methodist Episcopal Church South hold its first General Conference in 1846. In turn, this separation prompted a lawsuit—familiar to anyone following denominational divorces today, including the one within the United Methodist Church—over who got to control church property.

In the case of the north/south split of the Methodist Episcopal Church, the most important property was the Book Concern fund generated by the publishing house then known as Swormstedt. The Methodist Episcopal Church South claimed that it owned a proportional amount of that fund—which had been designated to support itinerant ministers—and sued to recover it. The contingent of the Methodist Episcopal Church that remained in the North, in contrast, claimed that they were the rightful full owners of the fund. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was decided in 1853 in favor of the southerners. The Methodist Episcopal Church South could access a portion of the money to fund their own ministry among pro-slavery Methodists in the South, and ultimately in the Confederacy. Today the case is understood as a milestone in the case law around church and state.

When the book on my shelf was “confiscated” in April 1863, then, it had already been at the center of a larger conflict over Christianity since before its publication, for a decade at least. It was a set of unremarkable notes on gospel texts, but implicated in a struggle over the meaning of religion itself, and for human dignity. There is no way to know whether the “yankies” who took the book understood any of that history, or whether they simply wanted some reading material to occupy their time within the drudgery of war. I also have no way of knowing how the book found its way to the Iliff Student Senate book sale, though I would very much like to know what series of hands it passed through on its way to me.

I have kept this book in my office because it is a helpful reminder of something obvious: that the story of Christianity is interwoven with histories of violence, oppression, and hatred. Some of those histories continue into our present, and they will extend into our future as well. We might wish to build a wall around our own traditions and institutions, to insulate them from the past and any future evil, and to insist on the purity of something like Christianity. But even in the mundane history of something like a tattered old book, we can feel the ways the good is entangled with the bad, the truth layered with lies, beauty mixed up in ugliness.