Before we start, two programming notes.

First, thank you to everyone who chipped in to support me and this Substack last week. Over twenty of you responded to the call and joined about thirty who were already supporters (some of whom raised their support). It means a lot financially, but it also means a lot to me personally to know that you’re out there reading and appreciating and sustaining this writing.

Second, longtime readers will have noticed that I always link to the lectionary texts at the Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. I’m an alum of that school, and they do a great job with the lectionary! But last week they redesigned their site, and all the old links are broken now. I’ll use valid links going forward, of course, but I can’t go back and fix the old ones—it would take forever. So if you encounter a broken link while journeying through the archives, just visit the main site and you can navigate to the appropriate texts from there.

OK, on to this week’s texts!

What do we want from power?

I’ve spent the past two weeks teaching a public-facing class on how to read the lectionary texts of Advent and Lent with a postcolonial perspective—how to read them, essentially, with a steady and suspicious eye toward power. It’s interesting to notice how, in Advent, the language of power and kingship shows up as hopeful, grand, noble, and good. In the texts for Advent, expectations of a messiah are hopes for a kingly figure (more or less), and the season is grounded in the hope that a powerful person (the messiah, Jesus in the Christian tradition) will set the world right and put a stop to suffering and oppression. But in Lent, a lot of this dynamic is reversed. Suddenly power is jealous, violent, capricious, and invested only in itself. The story turns on the insecurities of powerful people. Jesus is shuffled between a governor and a king on his way to die on an imperial cross. In Advent, Christians place a lot of hope in power, and by Lent we have grown wary of it.

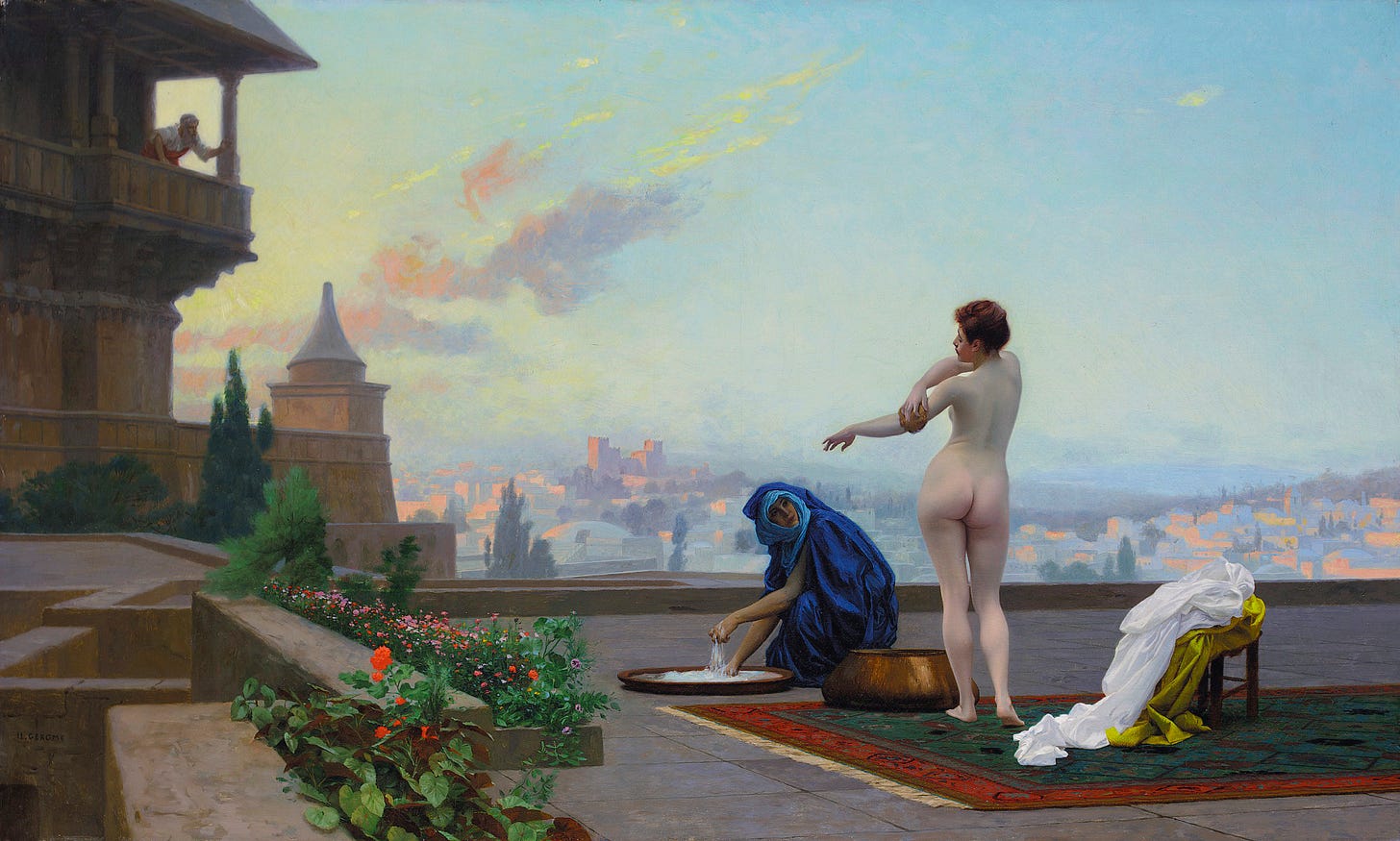

I was thinking about this dynamic as I read the passage from 2 Samuel in this week’s lectionary. This is a famous text, and it describes a famous figure. David is the paradigmatic king in Israel’s history—the OG, as the teenagers say these days, unless you count Saul (which nobody does). According to the traditions about him, David unified disparate tribes and founded a royal city and a royal lineage. He’s described at one point as “a man after God’s own heart,” and he seems to have had a special relationship with God. David is portrayed in various tender kinds of ways: as a shepherd boy, as a talented musician and poet, as a visionary leader, as a faithful follower, and as someone who danced before the Lord with all his might. But he’s also described, in this passage, as a predator, an adulterer, and a murderer. All the trappings of power are here—the same power that readers might cheer in other circumstances. David has a palace and he commands armies; he has servants who do his bidding. These are the things that make a king seem kingly, and turned to the right purposes, they are the kinds of things that lie behind the good associations with power we have in Advent—the kinds of things we imagine Jesus bringing with the Kingdom of God. But in this passage, David takes all his power and he turns it to wrong purposes—to abuse, predation, murder, and arguably sexual assault.

(Some might object to labeling David’s actions in this story as sexual assault. It’s true that we don’t know and will never know Bathsheba’s frame of mind in this encounter—whether she was a willing participant or not. But if part of the ability to consent lies in equal power dynamics, free of coercion and threat, then having the king (your husband’s boss) summon you for the purposes of having sex with you is unlikely to ever meet the standard).

I’ve always found it remarkable that David is described this way—that a story like this is part of how David’s character is presented, and that this story made it through whatever processes of storytelling and compilation and editing produced our modern Bibles. Even if you grant that Bathsheba was into it, this is a tale of a grievous sin and betrayal. It’s not only adultery and it’s not only murder—and after all, kings have people killed all the time. (The passage opens with a breezy description of how the army “ravaged the Ammonites”). But what compounds this story is the way David takes advantage of his power, pulling all of the levers of leadership available to him, to benefit only himself and to betray the trust of people who had placed their trust in him. He was a powerful man who wanted something and used his power to get it, because it cost him nothing to do it—although it would cost others quite a bit.

So what do we want from power? Maybe we want our people in power so that other people—the ones we don’t like—won’t have power.

We who live in the United States are in a season right now of intense anxiety about power. It’s presidential election season, which is wonderful if you’re in the cable news business and exciting if you feel hopeful, in that Advent-y kind of way, that meaningful change is just around the corner. But for many of us, election season is more of a Lenten kind of time—a time to be suspicious of power and the people who seek it, and a time to despair that it’s not positive change but catastrophe that lies just around the corner. We see candidates, especially the candidates we do not like, as omens of power ill-used and wrongly gotten. We fear the things people would do with power, and we don’t always even trust the things our preferred candidates say they would do. We spin out scenarios of what this or that person might do if given the chance, often using the fear of what’s possible more than hope of potential futures to motivate our actions. (The Bible does this too, with kingship. Look at 1 Samuel 8:11-18 for some election-season negative campaign messaging).

So what do we want from power? Maybe we want power to defeat our enemies for us.

In that passage from 1 Samuel that I just linked to, Samuel is warning the people that when you elevate someone to power, you’re not only giving them power over your enemies and the power to make you feel prosperous and safe. You’re also giving those people power over yourself and the people you love. I think that’s what this passage from 2 Samuel, the one in the lectionary this week about Bathsheba, is driving home: it’s hard to separate the kind of power we like from the kind we don’t. It’s hard to give someone enough power to lead a country (or an institution, or a congregation, or a city council, or a diocese or conference, or a family, or a corporation) and also ensure that they won’t use that same power to benefit themselves. We can put ethics rules in place and guardrails around things, but powerful people are powerful people, and usually they can step right past those boundaries if they want to. “When you’re a star, they let you do it,” in the words of one of the world’s great afficionados of power. Whether they “let you do it” or whether like Bathsheba they had no other choice, we all know countless stories of powerful people abusing their positions and the helpless feeling that comes from realizing that there isn’t anything you can do about it. A strongman might be appealing, in a certain kind of way, until he notices you and decides to use his strength against you—until he decides to take what you have, because he can. That was essentially Samuel’s point in that passage I linked above: you think you want a king, until the king acts like a king to you.

So what do we want from power? Maybe we want the ones in power to promise to fix everything so we don’t have to.

David was apparently polling high on national security, defeating the Ammonites and besieging Rabbah—or, at least, David’s armies and commanders were doing a great job of prosecuting his wars for him. Maybe that’s what made him feel so entitled to take whatever he wanted; he knew that so long as his armies were winning on the battlefield, no one would question him if he took advantage of Bathsheba or sent Uriah to his death. (Notice that Uriah is a Hittite—not an Israelite. Maybe Uriah’s foreignness emboldened David to commit violence against him, as often happens). In many organizations, from companies to churches to nations, we are tempted to outsource power to the people who promise to make everything easy. We want someone who will defeat our enemies and overcome our difficulties for us without us having to do too much. We want someone to fix the budget, articulate the vision, conquer market share, or restore the nation to some prior age of glory—but we don’t want to have to participate.

So what do we want from power? Maybe we want people in power to be more than human.

Or, at least, we want people in power to promise to be more than human. We want people in power to tell us how they will fix everything, how they will conquer our enemies, and how they will make our lives easy. We want people in power to tell us how right we are, how we deserve better, and to promise that they alone can fix things. We want superhuman leaders. That’s how David is portrayed in the historical literature, as almost too good to be true: poet, musician, warrior, leader, unifier, dancer, king. That’s how leaders sometimes present themselves, as uniquely qualified and solely capable of making our lives easier and leading us to glory. Some leaders deliver on that promise, while others don’t.

I could go on about power. (I haven’t even really talked about how we often submit ourselves to a strongman in exchange for the promise that we, too, can have a tiny share in the domination. Notice how, in the 1 Samuel passage I linked to above, Samuel predicts that the king “will take your male and female slaves,” implying that everyday Israelites would be deprived of this smaller form of domination over someone else). We are all familiar with how power works, and we all have experiences of encountering power and powerful people. The Christian story is a dance with power, both trusting in the future power of Jesus and mistrusting the way power shows up in the world—singing Advent hymns of liberating power while also singing Lenten hymns of loss and violence. The story of David and Bathsheba captures so much of that ambivalence of power. It tells of the trappings of kingship and nation, the glory of an army on the move, the way a people builds a palace for its king. But it also pulls back the curtain to show how our fantasies of power come to destruction in the unchecked ego of a despot, the willingness of commanders to carry out unethical orders, and the way the costs of power are borne by everyone but the powerful.

Wow - really good word(s) about power. Thank you for these insights 🙏