Probably like many of you, I have spent the past couple of weeks thinking about what I want out of my government and my country and my leaders—and also thinking about what I don’t want. The spate of end-of-term Supreme Court decisions left me feeling like something has been forfeited from among the most essential values of our society. A steady drumbeat of mass shootings has punctuated the news, as they always do. The calamitous presidential debate gave nowhere for someone like me to find any inspiration or hopeful sentiment. The effects of climate change are showing up everywhere, casting a sense of doom over everything. And on the Fourth of July, the fireworks in my neighborhood felt more like a senior prank than an outpouring of joy or patriotism—one last night of lawlessness before everyone moves on for good. The rockets’ red glare illuminated a lot that many of us would have preferred to keep ignoring.

I always appreciate the work of Tressie MacMillan Cottom, and her column this week is no exception. She watched the debate in a pub in Ireland and then continued her travels to Greece, which prompted her to reflect on it differently than she would have if she had been watching and reflecting in the United States. She always feels most American, Cottom says, when she is traveling abroad, and I fully agree. When I have spent time in Italy or Scotland or Turkey or Cuba, I have marveled at the different foods and the different music and the ways the landscapes afford different lives to the people who inhabit those places. I see their sensible cars (not a lifted pickup truck or an eight-passenger SUV in sight) and their efficient trains and walkable cities and wonder why my own country cannot find the nerve to acknowledge good sense. I always find myself imagining what it would be like to live elsewhere, to organize my life along the rhythms and logics of a different place. But there always comes a time when I begin to feel my American-ness insisting on itself. I long for the foods of home and the shops where I can find them. I crave the fierce upswell of American culture and music and art. I feel the absence of the United States’ diversity of people, and in many places I start to notice how everyone looks mostly the same. I miss the feeling of knowing and being known, the casual ease of familiarity and belonging, and I realize that for better and for worse, I am an American.

But when it comes to political life, that feeling of belonging makes my grief harder and not easier. The failure of American politics is so difficult to bear precisely because I belong to America and America belongs to me. The crumbling of the foundations would be easier to accept as inevitable, if it wasn’t the house where I lived. The raging id of Americanness, expressed by egomaniac politicians and wannabe fascists, would be easier to analyze intellectually or dismiss as a sideshow if I didn’t have to live with the consequences. It feels mad, sometimes, to be an American—like being locked in a room with three hundred million versions of yourself, some better, and many much worse.

So, what do we want out of our government and our country? What are we asking for when we judge the candidates in a presidential debate or feel despair at a Supreme Court ruling or shake our heads at another mass shooting? I think we are asking for the better versions of ourselves; I think we are hoping that someone will come along to teach us how to be together, better. I felt that way about Barack Obama—the only time I have ever felt inspired by a president in my life. Perhaps others felt that way about George W. Bush or Bill Clinton, like those leaders could be the ones to elevate our common belonging and make it mean something worthwhile. Certainly people feel that way about Donald Trump, inexplicably, and maybe some people feel that way about Joe Biden. But I do not, and so I am left adrift, wondering whether it is better to belong in a country where I sometimes feel mad or to make a life in a country where I do not belong. Perhaps you know what I mean.

We are not the first to feel this way. The tension between belonging and estrangement is one of the animating anxieties of all political life, social life, and religious life. As long as people have lived in groups, they have had to negotiate the push and pull of each other and the things that spring into existence between them—the state, the nation, the group, the religion, the family, the band, the tribe, the sect—the spaces they inhabit together. Human beings spend so much of our time on the question of whether and how we belong together because that’s where so much of the meaning is made in our lives. We fight over it, and we fight for it, precisely because it matters so much to us.

Ancient people were no different. In the lectionary for this week, three of the texts focus in some way on this question of collective belonging and the way it shows up (or not) in governments and leaders. In 2 Samuel 6, we find a scene of joyful celebration, led by David the king, in which “all the house of Israel” danced before God. In Amos 7, the prophet delivers a judgement against the leaders of Israel that would sound familiar in our own place and time. And in Mark 6 a fearful king with unchecked power hunts down and kills someone trying to hold him accountable. All three of these stories meditate on leadership and its possibilities. All three ask, even if obliquely, what kings are for and what kinds of collectivity might emerge from our midst. All three stories keep an eye on the grisly underside of power, the ways it can all go wrong, and the necessary danger of investing so much in leaders.

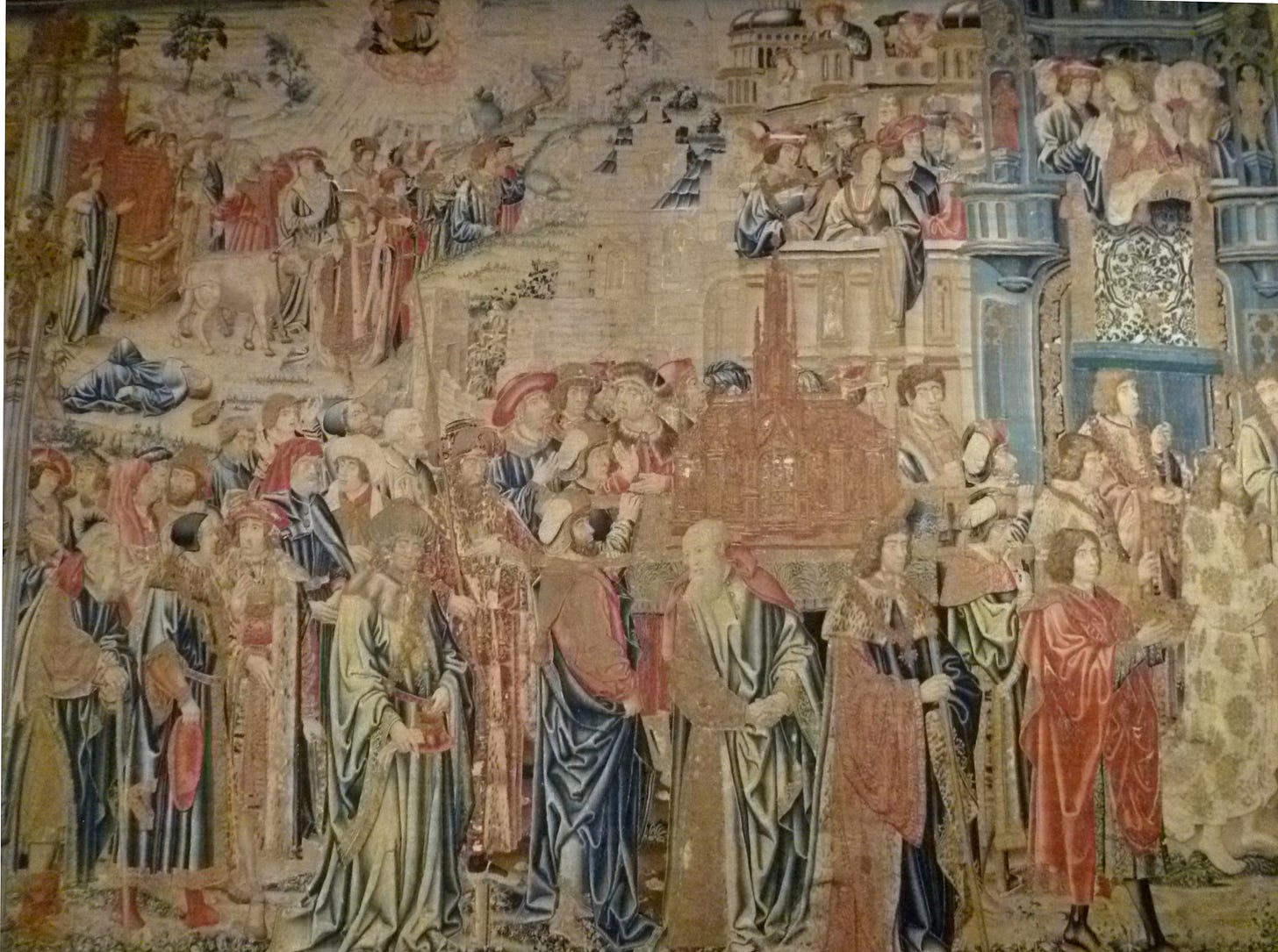

2 Samuel 6 is a beautiful text, but laced with fear and violence. It describes an intense moment of absolute elation in Israel’s history, the procession of the Ark of the Covenant into the city of Jerusalem, symbolically marking the end of a period of placelessness and wandering and the beginning of a stable and settled life together. This scene represents the bringing of God’s presence into a new City of David. The text as it is found in the lectionary—6:1-5, 12b-19—mostly focuses on the dancing, the music, and the effervescent joy that accompany that moment. David the king leads the procession; “David danced before the LORD with all his might.” But the parts that the lectionary leave out make it a more complicated story. In 6:6-12a, the cart carrying the ark was jostled, and one of the cart-drivers reached out to steady it. The cart-driver’s name was Uzzah, and the text—this part is omitted in the lectionary—says that “the anger of the LORD was kindled against Uzzah; and God struck him there because he reached out his hand to the ark, and he died there beside the ark of God.” We see here two visions of belonging, and two visions of power. We see David the king, at the head of a joyful nation, kicking up his feet in time with the “lyres and harps and tambourines and castanets and cymbals,” leading from the front in a moment of national glee. And we see God—the LORD—jealous and vindictive, wielding power in a way that seems capricious and unfair. I wonder whether the lectionary does us any favors by giving us the joy and sparing us the violence. And how much is hinted at about the difficulty of belonging together, in 6:16, in the glimpse of the seething loathing of Michal?

This passage is about what we want from our leaders, isn’t it? We want them out front, leading the procession, leading the dance, and giving shape to a new and newly settled future. We want our leaders to give us someone to follow and show us what it means to have something to believe in and celebrate. But in the part the lectionary leaves out, this text also shows us what we fear: the way power (in this text, God) arrogates to itself the ability to control our lives and to inflict violence at a whim. The fate of Uzzah haunts every human collective; Uzzah was dancing along with everyone else, in fact taking the lead on taking care of the collective good, until he was struck down for doing what he thought was right. This passage feels unfair in the same way all fickle uses of power feel unfair, from policies like Jim Crow to Supreme Court decisions on executive immunity to the demise women’s bodily autonomy to casually dealing weapons to other violent regimes. We want David leading the procession, but we also want Uzzah to live out his days untouched by vindictive anger. And it’s sometimes hard to have both.

The book of Amos also gives us both God and king, through the story of a prophet. The king here is Jeroboam, the first king of the northern kingdom of Israel after the split from Judah. The prophet is Amos, who claimed to be “no prophet, nor a prophet’s son, but…a herdsman, a dresser of sycamore trees.” And God is still jealous, still violent, promising judgement on Israel and especially on Jeroboam. It’s a familiar story, if you know the Hebrew Bible. The people have been unfaithful and God has become angry, threatening the destruction of the nation at the hands of its enemies. The prophet delivers the oracle: “Jeroboam shall die by the sword, and Israel must go into exile away from his land.” But the king doesn’t want to hear it, and he sends Amos away, putting the criticism out of sight and out of mind, and the reader knows at that moment that Jeroboam will lead the people right into the hands of God’s righteous destruction.

We sometimes think about prophecy as future-telling, but in the Hebrew Bible it’s really a form of truth-telling. Prophecy was a check on royal hubris and the isolation that hovers over the top of things like a cloud. Leaders—not least people like presidents and kings—can become cut off from the people, disconnected from the kinds of truths that bubble up from below. The job of prophets was always to deliver those messages, consequences be damned, and let the king know the truth. Prophecy was always framed as divine oracles—the word of the Lord—and that may be true enough. But in practice, the words of the prophets served as an almost-democratic check on the power of monarchies, offering a way for inconvenient truths to get through like a sunbeam through the cloud. Today we would point to a thriving free press, academic freedom, public opinion polls, peaceful protests, and public theological voices as analogues to the prophets: people and institutions charged with truth-telling and supposedly insulated from the blowback. In the Hebrew Bible, when a king like Jeroboam started going after prophets like Amos, that’s when you knew he was cooked, and the people were doomed. In our own time and place, when they start going after the universities and the journalists and the protesters and all the other tellers of truths, you know we are sliding into a dangerous place. In my opinion, we have been sliding for a while, and we are already well on our way there.

Mark tells us about another king who’s not so different. Herod is also afraid of prophets, though he does not seem to be afraid of God. As the story begins Herod has imprisoned John the Baptist for the crime of criticizing Herod’s marriage to his brother’s wife, and by the time the story ends John’s head is on a platter being presented to Herod’s daughter Herodias. Here is a vision of royal jealousy and fear, a cautionary tale about truth-telling, and an unnerving glimpse into the motivations and pastimes of the people at the pinnacle of government. While we might want our leaders to be better than we are, it turns out that many of them are much worse.

One of the interesting things about this story, for me, is that there’s nothing heroic about it. We might have expected John the Baptist to say something devastatingly witty to the king, to escape in the night, or to be protected by the power of God like Daniel in the lions’ den. We might have expected John’s followers to intervene, call in a favor, or smuggle him out. But John was beheaded in a prison cell by an anonymous guard, and his head was paraded around as a party joke. We have a tendency to romanticize resistance to power, and imagine ourselves (or others like us) like action movie heroes. Americans own hundreds of millions of guns, bought with just this fantasy: that someday we will use them against soldiers sent by a tyrannical government. But when power goes unchecked, the story usually reads like John’s story, and most people either join the side of power or get chewed up by it in the end. There aren’t many action movie heroes in real life.

Reading these three passages and thinking about what it means to be an American in the election season of 2024, the message seems clear to me: we must invest in better forms of belonging. It’s easy to be cynical or withdrawn and throw up our hands and scoff at the brokenness of the political system. It’s easy to look at political opponents and decide that they are enemies, to be defeated not only at the ballot box but in combat if need be. (This TikTok by one of my favorite intellectuals, Jamelle Bouie, covers only a few of the most recent threats in that direction). It’s easy to conclude, as many on the right and some on the left seem to have concluded, that the only recourse is to violence and force. It’s tempting to take the path of Jeroboam and Herod.

But these three lectionary texts also remind us that the places where belonging feels most successful are not in exercises of power or demonstrations of violence, but in collective expressions of unity and values. Out of all the instances of leadership we see in these texts, only David’s dancing inspires us. Herod killed John the Baptist out of fear and maybe boredom. Jeroboam exiled Amos out of fear and denial. God struck Uzzah down out of the fiat of power. But David’s dancing inspired “all the house of Israel” to follow after him in an expression of common purpose and shared vision. David led from the front, with a kind of joyful clarity, and the people followed him.

I’m no politician or sharp political mind, but as I have spent the past couple of weeks thinking about what I want out of my country and my leaders, I have felt myself longing for someone who can do what David did: someone to shrug off the petty grasping for power and the threats of violence and the appeals to ethnic nationalism and the cynical calculated catcalls and dog whistles to people’s basest instincts, and instead lead. I say this not to minimize the precarity of American democracy, but rather to acknowledge that we are on the precipice, and to hope for some outcome other than victory for one side or the other. There will always be Herods and Jeroboams (and Trumps), willing to exercise naked power and unfurl violence to gain a total victory. We will always need to play the part of John and Amos, telling truth to tyrants. But once we have done that, we need to belong together too. We need to know how it feels to celebrate, to dance together, to move as one in a common direction, and to do that, we need someone to lead us.

I wish I had read this in the morning after a night of snoring, instead of just before bed, perhaps less snoring tonight. Night, all