I spent the last few days in Atlanta for a workshop with the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion and the Candler Foundry. The workshop was titled Community as Classroom, and it was designed to help us think about how to learn and teach religion outside of traditional settings like churches and seminaries. I’ll have more to say soon about that workshop (which will be ongoing for the next several months). But for now I’m struck with one big observation: whenever I gather with people working in the world of religion, whether it be clergy or academics, the conversation quickly turns to the decline of mainline Christianity in the United States, or what one of our workshop leaders called “the unraveling.” At the workshop, we kept returning to the unraveling again and again, comparing notes and trading rumors about plummeting enrollment, faltering institutions, and strained finances. Some of us who attended the workshop work in seminaries, some in undergraduate institutions, and some in parish ministry, but we all felt the unraveling really strongly, and as we compared notes we realized that we all spend much of our time trying to hold unraveling things together.

There’s a sense, in those conversations, that we are living at the end of something. It might not be the end of everything—some institutions and systems will surely stay bound together despite all the unraveling. But we all seem to feel that certain ways of being and certain approaches to the world are passing away, slowly and also all at once. Maybe you feel that in your own context—church attendance that dwindles and dwindles, or budgets that have been cut to the bone, or the steady draining away of energy and enthusiasm. Often, in those moments, there’s an instinct to think about the past—to remember the history of the system or institution that we are watching unravel. We remember the boom times, the prestige, and the giddy energy of it all, and we compare it somberly to the way it’s all now coming apart.

In our workshop, we read a book by Justo González, The History of Theological Education. González is one of the great living church historians, with a gift for synthesizing and communicating plainly (and a gift for churning out books), and while this book might seem like a niche topic, it’s really pretty relevant for anyone interested in the world of North American Christianity. The book surveys all kinds of approaches that churches have taken to equipping leadership, from catechumenates to universities to seminaries, and it traces the development of how churches have thought about what is important about being a religious leader. But—and—it’s also another one of those recitations of history, one of those rememberings of a thing as it is passing away, at least in its current form. The book remembers the early modern roots of modern seminaries as a way to wrestle with their diminishment and disappearance. It situates them historically in order to help us come to terms with their unraveling. I came away from the book a little comforted by the way the church has continued to evolve and reinvent itself, but also a little more resigned to the current way of things passing away.

Living at the end of something, and contemplating the beginnings and the history of that same thing, has me thinking about the view of the beginning from the end. How do we tell the story of our origins, and why? What prompts us to remember the way something started, and what’s at stake in telling that story when we know how things have turned out?

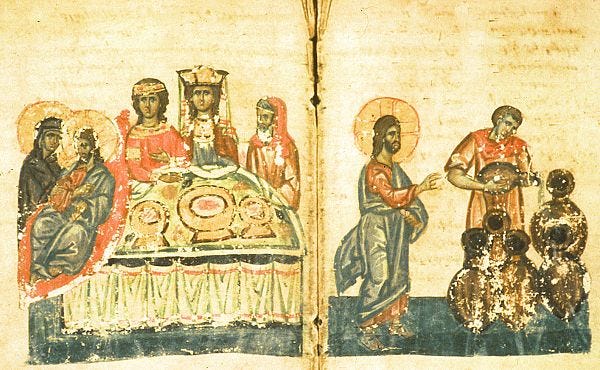

The gospel reading in the lectionary this week is a familiar one: it’s the story of the wedding at Cana. Even if someone doesn’t know the story, they probably know the expression about turning water to wine, and they might even know that it’s a characteristically Jesus-y thing to do. This story only appears in the Gospel of John, and not in any of the other gospels. It shows up in John as the “first of his signs.” So this transformation of water into wine is Jesus’ first real public act, and it’s the inaugural “sign,” which is what that gospel calls Jesus’ supernatural deeds, rather than miracles. It’s one of the first narratives of any kind about Jesus that shows up in John, before much of anything else has happened, and some scholars even think of it as an infancy narrative—a story of Jesus’ childhood or adolescence—because it’s a story of a precocious Jesus still traveling with his family and only just debuting his powers. It’s clear from its position within the gospel and some of the details of the story that we are supposed to think of this episode as one from the beginning of Jesus’ ministry, at the dawn of his importance, as a kind of inauguration of all the important things that happened later.

But the Gospel of John was written long after this wedding at Cana happened, and long after the last of that miraculous and signifying wine had been drunk. Scholars disagree on the dating of John like they disagree on almost everything, but even the earliest plausible dates for the composition of the first parts of the Gospel of John put this remembrance a solid generation after the event it describes. Most dates for John would put it two or three generations later. It’s a memory of an event from the beginning, told after the end—after Jesus’ ministry, after Jesus’ crucifixion, after Jesus’ resurrection, and after people had begun to collect and recollect the stories of Jesus’ life. It’s a story about the halting origins of Jesus’ power, told from the perspective of people who had come to believe in his resurrection from the dead, and who had come to believe even in his divinity. As a story, this passage from John holds back, and it does not reveal all that its writer(s) had come to believe.

What do we see in this story? Jesus is a little bit reserved, uninterested in showing off his power and reluctant to unleash his abilities. “My hour has not yet come,” Jesus tells his mother (who remains unnamed in this story and everywhere else in John)—implying that Jesus has an hour which would yet come, later in the story. Here, though, Jesus is a beginner, a novice, an unready and slightly irritable son. But there’s the glint of something more in the light reflecting on the water in the jars—the hint or suggestion of all the story yet to be told. The view of the beginning of the end can’t help but give a little of the ending away; the storyteller can’t help but glance toward all the things that were still to come.

When we are near the end of something, and we tell our stories about the beginnings of those things, we can’t help but glance toward all the things we know will come to pass. “They were just a bunch of simple folk who recognized the need to educate pastors,” we might say as we describe the founding of a great theological school. “They banded together to start a church in the new town,” we say about the charter members of a community that lasted centuries. We often emphasize the practicality and limited ambition of the past, as a way to highlight how very grand the thing indeed became. That’s how Jesus is in John 2, and that’s how we often are as we bear witness to the unravelings of institutions in our own time. We adopt a kind of modesty when we talk about the past, trying not to know too much too soon, even as we know how the story will likely end. We try not to give it all away too quickly, even if we know where the story leads.

What was it like to live in the time when the gospels were being written—when these stories were being collected and committed to books? There’s a shift between the experience of living through something and the experience of commemorating something—between the moments when you know you’re actively experiencing history and the moment you find yourself looking back and remembering. For the generation that lived through Jesus’ ministry, I wonder what it was like to have been there for some really epochal events, and then to find yourself no longer an active participant but a bearer of memory. Was it bittersweet? Was it a letdown? Was it invigorating, to be the keeper of those stories? The gospels all seem to have arisen out of that moment when the story of Jesus’ life and ministry had clearly come to a close, when the last of his followers and friends were passing away, but before the Jesus movement had become all that it would become. The gospels all come from a “somebody should write this all down before it’s forgotten” kind of moment, but there’s a conflictedness to that moment too, a perception of the unraveling, a recognition that you’re viewing the beginning from the end.

The transformation of water into wine is a fine sign for a time of unraveling. Water is ordinary—essential, foundational, and vital, but ultimately ordinary. Wine is special, especially the wine that might be served at a special occasion. John, as he was looking back and picking out the things that seemed most important to say about the beginning from the standpoint of the end, chose to tell a story of the ordinary turning into something extraordinary, and the story of a reluctant and irritable son beginning to turn toward something greater. The first of Jesus’ signs was prodded out of him by his mother, somewhat against his better judgement, but the author of John remembered it as a moment when the ordinary began to transform into something different—something more. And perhaps John meant it as a sign for his own time, a time when all of the extraordinary things about Jesus’ ministry lived in the memory of the past. Perhaps John meant this sign of turning water into wine as a view from the beginning to the end, to a time when ordinariness reigned again—a reminder of how strange and wonderful things can overtake us.

We who are living at the end of things should try to remember that strange and wonderful things are likely to intervene at any time. We are caretakers for the achingly ordinary: institutions that falter and fail, traditions that dwindle and die, and stories that fall out of memory. We might spend more of our time remembering than imagining, and more time managing decline than dreaming up the unthinkable. We are running out of wine, and we know that it will not be enough. But this story from the beginning of Jesus’ ministry reminds us that the ordinary moments are the ones when extraordinary things happen, and that times of scarcity can turn quickly into unexpected plenty. John remembered that, and he thought it was a story worth telling. We can hear it, and know that it is a story worth remembering.

Reading parts of this out loud to Debra (who was looking for music ideas for this weekend), I really noticed how truly good your writing is.

Thank you for sharing that with us.