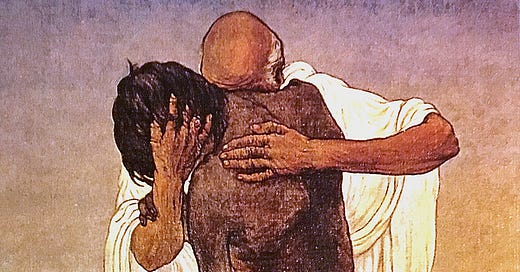

![Title: Forgiving Father

[Click for larger image view] Title: Forgiving Father

[Click for larger image view]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GYvU!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F94fea968-2272-497c-a4c4-d349b1831101_800x1491.jpeg)

When we talk about the ongoing decline of Mainline Protestant churches, we use a lot of different kinds of language. We use the language of statistics, which tells us that religious participation tends to rise and fall in concert with birth rates (which, in the United States, have been falling). We use the language of finance, which tells us that the kinds of budgets that were once easy to maintain are now unsustainable, and we use the language of real estate, which puts things in terms of monetary value. We use the language of politics, which points out that people are now sharply fragmented across political lines, and less likely to belong to organizations alongside people with whom they disagree. We use the language of culture, claiming that people’s priorities have shifted, and we use the language of theology, which can help us recognize the ways the church has not always lived in the fullness of God’s calling, and the ways the church has run off many of the people it now says it wants to include. But there’s one kind of language we don’t use enough, in my opinion. When we talk about the ongoing decline of Mainline Protestant churches, we don’t speak often enough in the language of grief.

The gospel reading for this week, the Parable of the Prodigal Son from Luke, is a story about grief. We don’t always read it that way, of course. We read this as a parable about profligacy and wastefulness, and we read it as a story about the way love overcomes all kinds of wrongdoing. And it is a parable about those things. But at its core, this is a parable about loss—the loss of home, the loss of a child, the failure of a promise—and it is a parable about the way grief can consume us and motivate us.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this parable over the past few years, because I was working on an article that was recently published in the Journal for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies. It’s an academic article, so it can be a little dense and technical, but that link will take you to it, and it’s free to read. In that article I looked at exactly this passage—which I called the Parable of the Man with Two Sons, which is the language that Jesus uses in Luke. In the article I used a variety of theorists from the world of queer theory—Sara Ahmed, Jack Halberstam, José Esteban Muñoz, Lee Edelman, and others—to talk about how this parable imagines the father-son relationship and the patterns of inheritance upon which society is built. To make a long story short, I argued that when the younger son took his inheritance early and opted out of the socially-expected process of waiting for his “turn” to stand in full stature as an adult, he violated some of the rules of the game. (The game—and its rules—were different in the 1st century than they are for us today, but then again they are not too different). The father’s grief was not only an interpersonal one; it was grief that flowed out of the realization that there would be one less person to replace him in the social order and perpetuate the family name and business. The older son’s anger was a form of grief, because he realized that he was trapped in a system over which he had little power and agency, even though he had a lot of privilege in it. And the younger son felt the simultaneous grief of wanting out of the system of inheritance and also missing the security it provided. To take a broad view, I was arguing in the article that the Parable of the Prodigal Son is both a critique of dominant social orders of reproduction and inheritance, and a reinforcement of it. Like the father in the story, we want the next generation to be free to escape from the patterns that have ensnared us, and like the father in the story we also, on some level deep down, want to pass on our most cherished traditions and possessions and have them keep them for us forever.

Which brings me back to church. I spend a lot of time in and around churches, especially Protestant Mainline churches, and I think grief is the dominant mood in most of them. Sometimes that grief shows up as frustration, conflict, anger, disappointment, nostalgia, or even desperate hope, but I am convinced that grief is at the bottom of it all. In most churches I know, the conversation goes something like this. We were thriving thirty years ago, but now we don’t know where all the young people have gone. We are ready to be in ministry with young families, but they don’t seem interested. We have a building, but it’s emptier and emptier every Sunday, and we have traditions, but they are harder and harder to carry on. Most of us are getting older, and we just want to be sure all of this carries on after we are gone.

Notice, first, how familiar those words probably are. And then notice how much it has to do with inheritance, and how much it has to do with grief. We (which is the word I will use for the “we” in the italicized section above and the “we” who are writing and reading this Substack) remember the good days. We know, in our bones, how valuable and life-affirming our traditions have been for us, and we believe in those same bones that they can be valuable and life-affirming for other people too. We grieve that there seems to be no one to pass all of this along to. We grieve that all the things we love so much, from buildings to Christmas Eve traditions to beloved hymns to fellowship groups to potlucks, seem likely to die with us. There is no one interested in inheriting all this from us, or not enough of them. Like the younger son in the parable, the heirs have declared their non-interest and they have gone off to do other things. Like the father, we are not sure whether we will see them again, but—and—we desperately want someone to pass it all on to, so that it doesn’t die with us. Like everyone in the story, we are hoping that something will change.

Those theorists I mentioned above, the ones I used in the article, all point out the way our lives are guided by invisible structures. We are all tracked into roles and behaviors, many of them tied to our genders, from the moments of our births. In the Parable of the Prodigal Son, both sons were raised from birth with the expectation that they would take over the family farm and become the leading men of the family. (Notice, though, that the same expectation does not apply to the enslaved people and hired hands who show up throughout the story, in verses 17, 19, 22, 26, and 29. And notice how the story makes no mention of a wife or mother, or of any daughters. Then, as now, these invisible structures nudge some of us toward prominence and inheritance and flourishing and others of us toward invisibility and servitude). Both sons had their future mapped out for them from the beginning. Notice how neither son is very satisfied with that state of affairs; the younger son opts out, while the older son in verses 29-30 has begun to notice the ways his own needs are secondary to the needs of the family.

The younger son asks a simple and revolutionary question: what if I jump the guardrails? What if I refuse to go along with this plan; what if I decline to be groomed as a replacement for my father? If you have ever tried to go against the flow of your family’s expectations of you, you know how brave the younger son had to have been. If you’ve ever bucked society’s expectations for your behavior or for the trajectory of your life, you can understand where the younger son is coming from. He’s depicted in this story as wasteful and thoughtless—his older brother accuses him of wasting money with sex workers, which the reader is supposed to understand as the gravest of insults—but in a very real sense he is only trying to be free. The younger son doesn’t want to become his father, and he doesn’t want to die on the same farm where he was born. The younger son wants to live life for a while on his own terms.

The choice for churches is a little bit different, but still familiar. Like the father in this story, churches usually have stuff. (If you read that article I linked above, you’ll see that I translate one of the key Greek words in this passage, the one often translated as “property,” as stuff). Churches have buildings, endowments, traditions, staffs, land, programs, budgets, partnerships—lots of stuff that has taken a long time to build up. So much of the anxiety in churches, and so much of the grief, is that we aren’t eager to let go of all that stuff. After all, we think it’s valuable, and it took us a while to get it. We inherited it from someone else, so who are we to let it go? The grief felt in many churches is simply the grief of realizing, like the father in the parable, that next generation is either dissatisfied with the terms of its inheritance, or it is uninterested in inheriting anything at all. The thing that has been so valuable to us isn’t as valuable to others.

I mentioned near the beginning that my article about the Parable of the Prodigal Son is grounded in queer theory and the work of a handful of queer theorists. I want to return to some of their insights. Part of what queer theory does, as an analytical tool, is help us to notice those invisible structures and patterns that govern our lives, and recognize how they push us in one direction or another. For example, the insights of Halberstam and Ahmed helped me realize how much the parent-child relationship in the parable still bears a resemblance to the ways I relate to both my parents and my children—how much it explains my role both as a son and as a father. It’s spooky, almost, to realize how much I have bought in to the hidden orthodoxies of reproductivity and inheritance—how much I have been guided by the invisible structures of propriety, role, status, and the like. The work of Halberstam and Ahmed help me notice that the things I want for my own children sometimes have more to do with me than they do with my kids, and I’m grateful for the way their work has shown me that, because it helps me think differently about the choices my children make (or will make).

But I’m especially guided by José Esteban Muñoz, another of those theorists, and by his vision of flourishing. In a nutshell, Muñoz asks, in his marvelous book, whether we can break the pattern set by heteroreproductive futurity. Can we, in other words, stop fantasizing about all the things this Parable of the Prodigal Son is about—status and appearances and property and normativity and position in society—and start asking instead about flourishing? For Muñoz, the answer lies in a kind of utopian vision that’s not located in the past (as many churches see it) or the future, but in the present. Muñoz is writing about the experiences of queer people who, like the younger son in the parable, have been shamed for wanting something more for themselves, or for wanting something different than the invisible structures of the world tell them to want. Muñoz wants to claim the possibility of queer flourishing outside of the norms set by the world. “Can the future stop being a fantasy of heterosexual reproduction,” Muñoz asks?

The church should ask itself the same question. Instead of waiting for “young families” to magically walk through the door, and instead of growing bitter about the way no one is left to pass it all on to, church should ask what invisible structures in the world make us believe that our inheritance is so precious in the first place, and that make us believe that a “young family” is the proper heir for it. What causes us to believe so strongly in the power of inheritance, and that children and young people are the only possible inheritors? What makes us grieve so deeply at the idea that no will come after us to keep it all going? What accounts for all that grief? What happens if the future does “stop being a fantasy of heterosexual reproduction?” And what happens if, like the younger son, some in the next generation decide to seek their flourishing elsewhere?

This parable ends in a strange place. The younger son has returned, the father is rejoicing, and the older son is indignant and disgruntled. It’s a happy ending, if we are judging on the terms of heteroreproductivity; everything is back in place for the future to unfold as intended. (But notice that the enslaved people are still laboring for someone else’s inheritance, celebrating someone else’s inclusion). But I wonder what would happen if we followed the story of this family another few weeks or months or years. Would the younger son remain satisfied with his reclaimed domesticity and security, or would he keep chasing a different kind of life? Would the older son be content to wait his turn? Did the stuff that the father had accumulated and the younger son squandered turn out to be as important as everyone thought it was? Having watched those invisible structures and guardrails fail and fracture, did anyone in this family ever trust them again? Or did they go off seeking, in the words of Muñoz, a different kind of utopia, a different form of fantasy, an alternative kind of flourishing? I think they might have.

And if they did, then what does that tell us about the future of the church?

Eric, this is a powerful message that is beautifully written. Thank you.