This month as we’ve been going through a Pride series, I’ve said several times that queer biblical interpretation is a diverse and many-faceted thing. Queer biblical interpretation can be about looking for and finding queer persons in the biblical text, to be sure, but it is also about many other things: noticing norms and messing with them, for example, or thinking about the future in different ways. Queer studies and the academic disciplines that have been influenced by it, including biblical studies, are often asking questions that push past orthodoxies and traditional ways of reading, and move into radical new ways of searching for meaning.

But sometimes, we don’t need the fanciness of queer futurity or the subversions of normativity that queer theory can bring. Sometimes, the most obvious readings are the ones to pay attention to—the places where the text shows us queer lives, even through barriers of culture and millennia of interpretation. This doesn’t happen often in the Bible, because the Bible was written centuries ago in a time and a culture when queer relationships were usually not recognized or honored. And the Bible has passed through ages of Christian theological formation, which has interpreted most hints of queerness out of the text. We can see glimpses, sometimes, of the possibility of queer representation in the Bible. I have written here, for example, about how Jesus chose family among Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, or how the Samaritan woman at the well (with her seven husbands) might have been someone who was trapped in heteronormativity while yearning to escape. We could find other examples of queer lives in the biblical text, and many scholars and other interpreters certainly have, looking between the lines of the Bible’s normativities and drawing out the places where queerness is visible in the background.

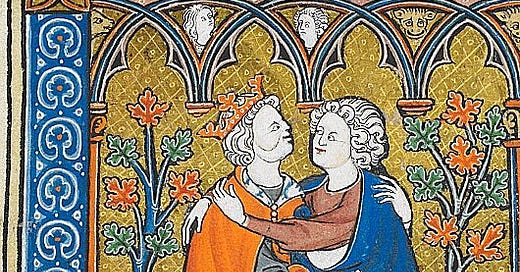

But the lectionary for June 23rd holds something remarkable. Rather than having to look closely or pick apart oblique references to queerness in the biblical text, in this week’s lectionary we have a forthright description of a queer relationship. 1 Samuel’s description of the relationship between David and Jonathan is bracing in its honesty and frankness. Listen to this:

When David had finished speaking to Saul, the soul of Jonathan was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul. Saul took him that day and would not let him return to his father’s house. Then Jonathan made a covenant with David, because he loved him as his own soul. Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that he was wearing, and gave it to David, and his armor, and even his sword and his bow and his belt.

After reading this passage, the only things standing in the way of acknowledging that David and Jonathan loved each other are heteronormativity and religious homophobia. It’s worth stopping to think about each of these things in turn.

By heteronormativity, I mean the set of assumptions about people that most of us carry around: the assumption that everyone desires people of the opposite gender, and the assumption that romantic attachments and relationships form along male/female lines. We have trouble seeing this description of David and Jonathan as romantic love because we have been conditioned to expect that men only desire women, and not each other. If this were a story about David and Jane, and not David and Jonathan, we would see the language of loving each other and covenant-making as the sure signs of romance. But because of heteronormativity, we call this something like a friendship. As a common meme puts it, “Oh my God, they were roommates.”

Religious homophobia is related; it’s a supercharged form of heteronormativity. Religious homophobia is like regular homophobia—the fear or hatred of queer people—but it is dressed up in religious garb. David and Jonathan cannot possibly love each other, the argument goes, because their story is found in the Bible, and the Bible is the religious text of Christianity, and Christianity forbids and condemns homosexuality. That syllogism operates in the background of our interpretations, limiting what we think is possible. But imagine, for a moment, that we didn’t have that argument in our heads. Imagine that we can pry this story away from its religious associations. Wouldn’t we see this as a clear and simple example of two people loving each other? The only thing keeping us from seeing it that way is the homophobia embedded in our ideas about what Christianity is.

I want to stop here and say that I am not necessarily making any claims about David and Jonathan’s physical relationship. The text doesn’t tell us that they were lovers, and the conditions of Iron Age culture might or might not have allowed for such a thing to happen anyway. But queerness is not always about sex, and whether or not David and Jonathan ever had sex, the text is clearly telling us that they were dear to each other, committed to each other, bound to each other, and public about it. That is already queer, in the Iron Age or today, because it skirts around our heteronormative assumptions and our religious presumptuousness. People are people, no matter when they lived and no matter what religious ideologies and texts they become attached to. Across time and place, some percentage of men are attracted to men, some percentage of women are attracted to women, and some percentage of people do not fit comfortably into binaries of gender and attraction at all. We should expect that we will encounter these people in the biblical text, just like we expect to encounter heterosexual people.

But why is this in the biblical text? Given the forces of heteronormativity and religious homophobia, how did we end up with this queer love story in the Bible? For me, the presence of this story in the text is strong evidence that David and Jonathan’s relationship was common tradition in ancient Israel, too widely known to ignore, and that it was considered an essential part of any storytelling about David. The David stories in the Hebrew Bible take a few different forms, and like many biblical stories the David cycles seem to be compiled from several different traditions. There are traditions of David as a musician, traditions of David as a shepherd, traditions of David as a warrior, traditions of David as a young usurper to the throne, traditions of David as sexually predatory, traditions of David as a poor household manager, and traditions of David as a lover of Jonathan. Rather than choosing from among these or trying to harmonize them, the Hebrew Bible presents them alongside each other, letting these diverse and sometimes contradictory traditions flourish together. The authors/compilers of the Samuel material and other parts of the Hebrew Bible kept these traditions together, and put them all in the texts, rather than choosing from among them.

Scholars have a word for the way someone in a text is described: characterization. Characterization refers to the way a character is built up, and the way that character works in the text. Before a character in a story does something important, often the author spends a lot of time showing us scenes that establish things about that character: what they’re afraid of, what they desire, what they need to overcome, what they have been through in the past, and so forth. All of that together tells the reader what kind of character they are, in the literary sense. The more that goes into the characterization, the more complex the character is.

David is a complex character. To begin with, there are lots of parts—the music, the shepherding, the story of Goliath, the predation on Bathsheba. And not all of these traditions about David were purely laudatory; more than most characterizations in the Bible, the David material is pretty conflicted. It seems to be interested in portraying a complex person, and a real person, even the parts that might run contrary to expectations. The material about Jonathan seems to fit into this pattern really well; it establishes that David had an intense bond with the family of Saul, even as he was in the process of usurping him, and that David’s posture as challenger to Saul was tempered by a deep love for his son and heir.

We can read David’s story this way, with his relationship with Jonathan forming a part of his characterization and helping flesh him out as a character on the page. But we can also read it as a simple affirmation and representation of a kind of love that the Christian tradition (and the Jewish tradition too) has often tried to deny and repress. This might be the best way to read this story, leaving behind the literary reasons that David’s relationship with Jonathan is in the text, and focusing on the way queer love shows up and breaks through the religious homophobia and the heteronormativity that can sometimes feel overwhelming. We might not always need fancy theories and exegetical methods. Sometimes it’s enough just to find queer love in a sacred text.