As readers may know, this Substack has an optional paid tier. If you subscribe to this Substack on a paid tier, you get a few benefits. Most of them are intangible, but one of the more substantial benefits is that you can assign me a post to write. A few weeks ago, one of my subscribers, Cheryl, sent this prompt over:

I would be interested in your thoughts on things like “many are called, but few are chosen” and “you didn’t choose me, I chose you”. I guess my question is …. If connection/call is all up to God, what does that mean?

This, I think, is a really interesting question—or, better yet, it’s a really interesting set of questions, both explicit and implicit. For me, it makes me think about the language we use to talk about religious devotion, commitment, interaction with the divine, and the kinds of work we do, all of which can be subsumed under the category of “call.” It brings up some complicated histories of how Christians have thought about their relationship with God, and how they have imagined God’s relationship with people.

First, before I get to the heart of Cheryl’s question, I want to pause to say a few things about “calling” in general. In my line of work, as a professor at a theological school, we end up talking a lot about calling, or one of its synonyms, “vocation,” which is taken from the Latin for “to call.” Students often arrive in my classrooms pondering call and vocation, or having had some experience of epiphany about it. That vocabulary of calling and vocation stand in for a whole range of things, that can vary from person to person, but it seems that most of the time it means that the person has experienced some kind of pull toward a particular kind of work. Many times, it means that the person has viewed ministry (religious work) from an outsider’s perspective for a long time, and has often wondered whether they would be suited for it. Or, it can mean that a friend or mentor has told them that they would be suited for the work.

Often, this takes the form of an assessment of “gifts.” Gifts, in this sense, are simply talents or skills that are a good match for a certain job. There’s nothing special about ministry or religious work in this regard; lots of different jobs require skills and gifts that are prerequisites for the work. It’s easy to aggrandize those skills, and elevate them to some special status, but I think most skills and gifts are valuable in many lines of work. An NBA player, for example, needs the gift of hand-eye coordination (among other things), as does a surgeon, a pilot, a house painter, and a line cook at a restaurant. A barista needs the ability to perform multiple tasks at once, but so does a childcare worker, a corporate public relations person, a farmer, and a mechanic. Many of the gifts required for ministry are not special to that line of work; most of them are the kinds of things that lots of different folks possess and use in a dizzying variety of jobs every day.

So, sometimes I wonder, when we talk about skills and gifts in relationship to calling, what we are really talking about. It seems like often we mean some version of the thing implied in Cheryl’s question: that God has equipped these people in a special way that makes them amenable to the work of ministry. There are even inventories, often required of people pursuing ordination, that assess skills like discernment, clarity of communication, the ability to self-differentiate, and organization. The idea is that these skills are not only needed for the job, but their very presence in a person is evidence that the person has been called by God.

Of course, if it were all about gifts and skills and a sense of calling, training would not matter. There would be no need to go through school or training for any job, if we simply relied on the idea that skills and innate gifts were evidence of readiness and were both necessary and sufficient to demonstrate proficiency. But these gifts are always a starting point, not an ending point. The NBA player and the line cook both need hand-eye coordination, but that doesn’t meant that each of them—which both possess a lot of hand-eye coordination—could swap easily into the other’s job. It also takes intense training to build competencies specific to the work required. This seems especially important in ministry, where a great number of people might possess some or all of the important gifts required for the job, but where training matters a great deal. And here we begin to move in the direction of Cheryl’s question.

What theological education or training does for a person—or what any form of preparation for ministry will do, whatever form it takes—is to cultivate a theological sensibility, mindset, worldview, or imagination. It puts the gifts and skills into conversation with each other, and into conversation with the world. Education and training will ask: How do the gifts possessed by this person fit the needs of the world, the understanding of ministry held by the person and their community, and the sense of call from God? How can the gifts be pointed toward a purpose? Even within a category like “ministry,” there are multiple specialties and emphases. For example, I am myself ordained, and I have worked in general ministry contexts, but I have a very specific set of skills (and absence of other skills) that fit into a fairly niche understanding of where I belong within the category of “ministry.” I am not a good pastoral care provider, either by inclination or training. I have little talent for the intricacies of budgets and finances, and even less inclination to learn. I can work with children, and have done so, but it’s not something I’m very good at or something I enjoy very much. Meanwhile, I flourish in other settings. All that is to say, my own sense of where I belong within a system of ministry or in the life of a religious congregation is shaped not only by the competencies I have naturally, but also by a lot of training that has helped me put together a view of myself as a professional, within a theological landscape, and even within specific religious communities.

So what about God? Cheryl’s question focuses on the way we often phrase the relationship between religious calling and divine agency. “Few are chosen,” we say, as if God is a hiring manager, or “I chose person X for this calling,” as if there were a lot of specificity in the way God thinks about staffing the needs of the world. Our language for divine calling, Cheryl is pointing out, is very one-directional, with God plucking people out for tasks.

Certainly the biblical tradition is full of examples like this, as is history. Abraham and Moses were minding their own business when God tapped them for a job, or so the story goes. People like Jonah and Paul were actually trying their hardest to go in the other direction. In late antiquity, bishops would occasionally be consecrated only after having been chased down and tackled by a crowd and ordained to the job by force; it seems that nobody really wanted the job when it came with a host of headaches and threats.

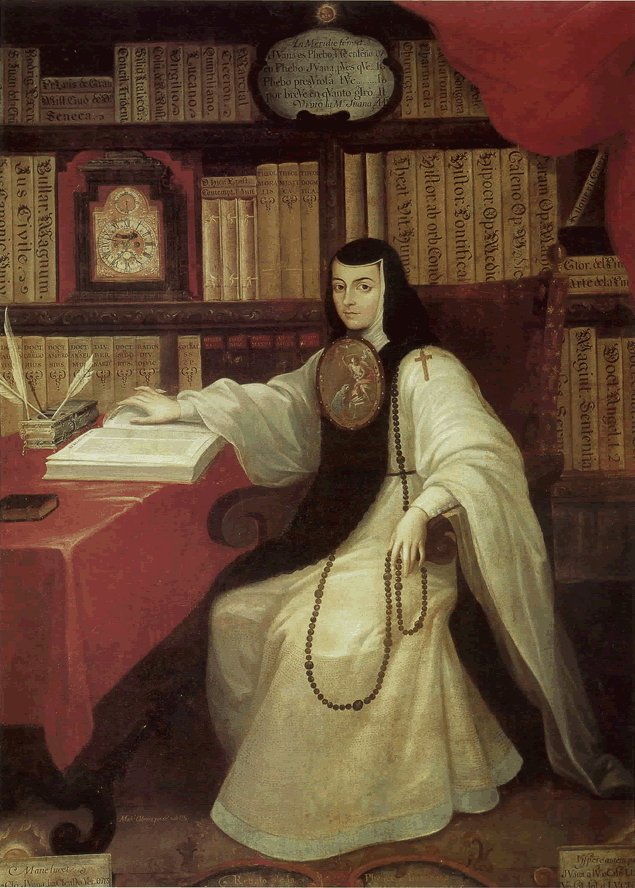

On the other hand, I think of people like Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Hildegard of Bingen, who flourished because of their skills and innate gifts despite being passed over for leadership roles (in both of their cases because of gender). They both seem to have been called by God, in both cases to intellectual and theological pursuits, on the basis of the kinds of competencies they displayed. But they also both seem to have been passed over by God, if we accept the Moses-and-Abraham-and-Paul model of calling.

There are a couple of biblical passages that come to mind when thinking about this. One is the genealogy of Matthew, found in chapter 1, in which a long line of ancestors is recited for Jesus. Among those ancestors are five women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba (listed only as the “wife of Uriah”), and of course Mary. What’s remarkable about these five women, and especially the first four, is that they fit this same model of calling as Hildegard and Sor Juana—they were overlooked, cast aside, and forgotten, and then seized agency on their own, through what we might today call “hustle” and initiative, and ended up becoming integral to the story of Jesus (as told by Matthew). The inclusion of these women in that passage alongside people like Abraham and David and Solomon suggests that something beyond “I chose person X for this job” is going on. These are people who took the job, grabbed it, and made it theirs, without being given it by God.

I also think of Hebrews 11:4-40, which is a litany of faithful and heroic figures. This passage has an almost call-and-response quality to it, which makes sense, given that many scholars think that Hebrews was originally a homily or sermon. Each of the heroic episodes in this passage is introduced with the words “by faith,” which to my understanding puts the onus on the individual’s actions and not necessarily God’s action. The particular actions of these people are all described as somehow moving the story of God’s people along. This passage could have been written as a series of “then God chose person X,” but instead it’s full of agency and action on behalf of humans—full of faith.

So, to come back around to Cheryl’s question, I am not sure that our stories and practices about calling and vocation match the language that we use for it. When we talk about it, we put a lot of emphasis on God’s agency, saying that God chooses people, but when we tell stories about those people, we emphasize their own actions and their own faithfulness, and the degree to which they were able to live out the gifts and skills they had. And in our own time and place, we view calling that way too, identifying gifts and then asking people to undergo processes of learning and formation to cultivate those gifts and put them into a theological program that helps organize them and make meaning of them. We might say that God chooses people, making it sound like a one-way street, but I think our practices and our stories about calling tend to flow in both directions at once.