Have you ever looked around—at the world, at your life, at a relationship, at politics, at your career, at an institution—and asked, where is this all going? Have you ever observed a circumstance and wondered what it could possibly be leading to? Maybe you’ve turned on the news in the middle of a presidential campaign and found yourself thinking that any possible outcome is bleak. Maybe you’ve found yourself working a job you don’t like without much prospect of advancement or change. Maybe the daily news has left you without any sense of justice or progress. Maybe the mundane details of things have overwhelmed you, and it’s hard to see your way to anything beyond that.

The fancy word for that feeling of seeking the meaning, purpose, or end of something is teleology. It’s a favorite word of mine. Teleology is from the Greek word telos, which means “end” or “purpose,” and that’s basically what it’s about. Teleology is about where things are headed, and why. When we encounter the situations above or other ones like them—when we feel like the country is mired in a middling place with no direction, or when we feel like we are treading water in our personal or work lives, or when we feel grief for a world caught in cycles of violence, we are frustrated with teleology—we don’t feel like things are going anywhere. When we don’t see a future for an institution or a relationship or a project, we are having a crisis of teleology. Where is it all heading, and if we don’t know, what’s the purpose of sticking with it?

Religion runs on teleology—or, at least, many so-called “Western” or “Abrahamic” religions do. Christianity in particular has a variety of teleologies: the beloved community, the Kingdom of God, the New Jerusalem, the resurrection of the dead, and the second coming, just to name a few. Christianity likes to point its way forward to a greater purpose or vision, and it likes to imbue the present with meaning by virtue of some future endpoint. This orientation towards the ends of things can be a powerful force in the midst of struggle, and it can give meaning to times that might otherwise feel meaningless. We might not be there yet, we might think, but we know that we are heading somewhere. Think of that famous maxim from Martin Luther King Jr.: “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Knowing the endpoint of something, or even just imagining what the endpoint might look like, can help us stick through the middle.

But one of the great tensions of religious life (and of, simply, life) is that many of the moments in our existence defy that kind of meaning-making. It’s not always clear where things are heading, and why, or whether they are headed anywhere at all. Sometimes there is no teleology to explain what kind of path things are on; sometimes there is no obvious outcome toward which all things are moving. Human beings have a hard time with this; we like for there to be a distant or future point toward which we are progressing. Think about some of the things that are most important to you (your family, your career, the politics of your country, your church) and think about the most frustrating times in your participation in those things. The most frustrating times were probably the times when things felt directionless and purposeless. Maybe your employer struggled to articulate a vision of the future or a reason for existing, or maybe your long-term romantic partner didn’t have the same kind of future in mind that you did. Religion often works the same way; even if we aren’t sure where we are in the story, we want there to be a plot, and we want it be going somewhere.

The lectionary for this week includes a strange and tragic story that makes me think teleologically. Like many lectionary passages, I think this one makes more sense if you include all the verses that the lectionary skips, so if you want to read it that way, click this link for the whole section of 2 Samuel. This is the climax of the story of Absalom, the third son of David, the king of Israel. At this point in the story, Absalom has rebelled against his father. He has sown seeds of dissatisfaction in the effectiveness of David’s government. Absalom ostentatiously sat where he could see people coming to Jerusalem for judicial proceedings, telling them that the justice system probably wouldn’t serve them well. In an act that looks pretty appalling from our perspective in the 21st century for several different reasons, Absalom has sex (it’s unclear whether it’s consensual or not) with his father David’s concubines (2 Samuel 16:21-22). By the time we get to chapter 18, Absalom is in open armed rebellion against David. It’s like something out of a fantasy novel, the son attempting to usurp the father and the father feeling conflicted about it. In 18:5, even as his son plots to overthrow him and they prepare to enter battle, David instructs his lieutenants to spare Absalom, because he loves his son.

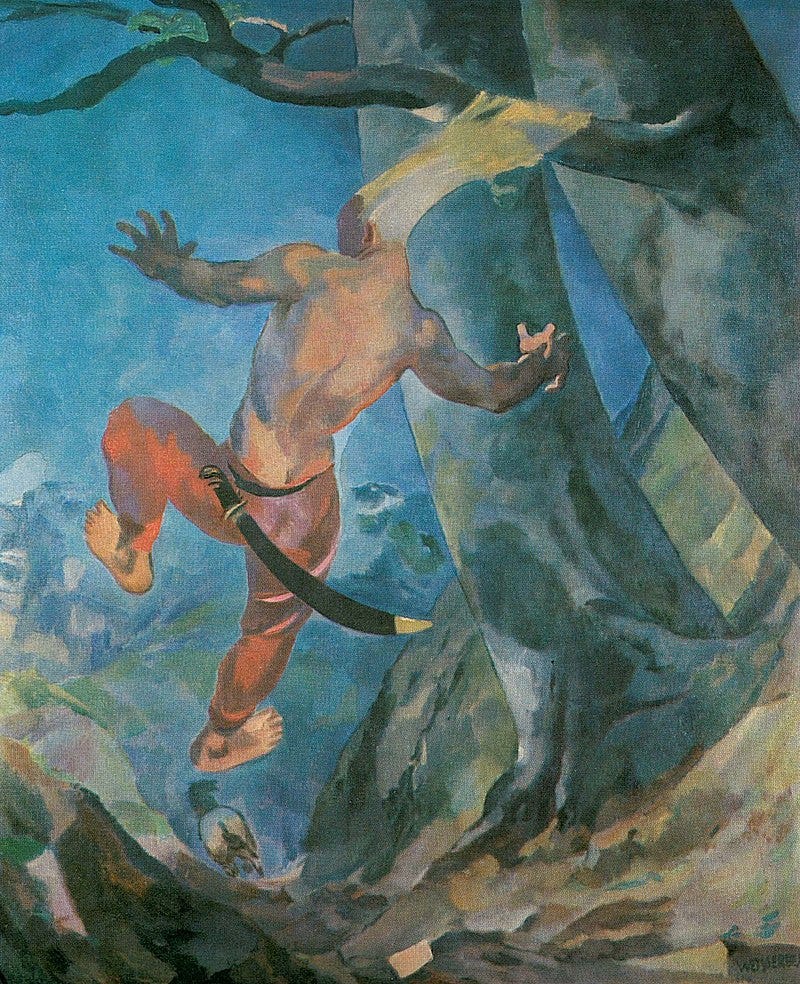

Absalom’s rebellion ends in tragicomedy: his famously prodigious hair (see 2 Samuel 14:26) gets caught in the branches of an oak tree, and the mule he was riding keeps on going. Absalom is left hanging by his hair in the air, stuck in several senses of the word, and enemy troops discover him there helpless and kill him, despite David’s orders to the contrary. Another small bit of comedy ensues as two different messengers, Ahimaaz and an unnamed Cushite, both run to inform David of what has happened—Ahimaaz conveniently leaving out Absalom’s death and the Cushite triumphantly reporting it, not understanding that David won’t hear it as good news. David is left in grief; in 18:33 he wails in mourning, “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!” The anguish is palpable even at a distance of millennia.

But with that kind of distance of time and place from this narrative, I find myself thinking about teleology. What is the purpose of this story? Where is it leading us? Why is it a part of the Bible, a collection of sacred texts, and what does it do for us as part of the lectionary, a cycle of readings meant to structure the church’s encounter with tradition? It is certainly a story with a lot of pathos, and it is entertaining, in a Game of Thrones kind of way. It’s an archetypal story of ambition and love and power, of generational conflict and violence. But in the midst of this story of palace intrigue and war, I find myself wondering whether and how it belongs in a larger story of salvation and redemption. Absalom’s story doesn’t seem to want to offer any clear moral lessons. It doesn’t illuminate David’s character very much, other than to show that he loved his son. God isn’t involved, except as the deepest background scenery for the main drama. Nobody comes out of this story a hero, though there are quite a few victims and villains. So what?

The story of Absalom, like a lot of the stories about David in the Hebrew Bible, is conflicted. There is glory and wisdom and honor, and there is also depravity and brokenness and degradation. Stories of David’s reign and tales of David’s household contain a lot of things that build him up into a magnificent figure, the great singular king of Israel, but they also contain a lot of things that show him to be deeply flawed and unworthy of praise—condemnable, even. Although Christians claim that Jesus was in the line of David and that therefore David’s kingship is important both historically and typologically, there’s nothing in this story that suggests that or points toward a future messianic importance. It’s just a messy story about a messy royal family, and it’s hard to root for anyone or see much greater purpose in it. The people living through it probably didn’t feel like they were experiencing some great turn in the wheel of history, and looking back from our vantage point, it’s hard to see much teleological meaning in the story of a family squabble with high stakes for a lot of innocent bystanders.

I can’t help but compare the way I feel about this story of David and Absalom to the way I feel as an American living in the year 2024. To me, being an American in the year 2024 feels like living in the middle of something, but it doesn’t feel like I’m living through an auspicious or glorious time in history. I don’t know where it’s all going. There’s messiness and conflict, but not a lot of teleological hope. There’s depravity and brokenness, but it’s harder to find the glory in it. Even if my side wins the next election, I don’t have a lot of hope that the country will be seized with clarity about a common purpose or new direction. I suppose I will probably live the rest of my life like the everyday people of David’s day, hoping that the people in power can get their acts together but feeling like it probably won’t happen.

I have noticed that the same is true, in different ways, for churches. Lately a lot of churches find themselves unsure of what comes next. It seems like many churches these days lack a teleology, aside from a vague commitment to survival. In some ways it’s like the story of David’s reign: a veneer of grandiosity and importance, hiding a kind of emptiness and directionlessness underneath. The trends in American religious life all point the same way, especially for Mainline Protestants: downward. The sense of decline is palpable in many churches and denominations, and we don’t really know how to think about teleology in a decline. We have learned to define our purpose and meaning and ends in terms of growth and expansion, so when we are in decline we are at a loss to say what it’s all about or where it might be heading. Decline only ever feels like failure, for so many of us, and so while we are shrinking we are also abandoning the search for meaning in our work, or else we are sticking with the same old teleologies that no longer serve us well or match our circumstances.

These situations might be the kinds of things that only really make teleological sense in hindsight. Both the United States’ currently political life and the systemic decline and collapse of Mainline Protestantism might only be intelligible in retrospect. We might not know yet where it’s heading, so it might not be possible to make meaning out of it yet. But then again, it might be the case that we can only ever escape these cycles when we are able to say clearly where we think we want to go. Vision is a discipline that needs cultivating, not a natural part of the landscape, whether we are talking about nations or institutions like churches. Why are we here? Why have we been where we have been, and why are we going where we are trying to go? What’s the endpoint that we are imagining for ourselves—the telos toward which we think this is all moving? When we lack a clear destination, or when we argue over which destination might be best, we get stuck moving in circles, or simply staying put.

This story of David’s reign feels that way to me. Obviously in the light of history David’s kingship turned out just fine; he is generally acknowledged as the greatest of Israel’s kings and the paradigm against which all the future and possible rulers after him would be judged, despite his many manifest flaws. But in this episode of Absalom’s death, we get a directionless David, with no vision or telos, no point toward which anything is moving. This is a David bereft and grieving, facing the decline of his power and great personal loss. That might be a familiar circumstance; many of us might feel that way right now about the world, our lives, and the institutions we care about. Perhaps these moments will only make sense later, as part of a journey we cannot yet see. But even if that’s true, I think it’s important to set our eyes to the horizon, and try to imagine what it would be like to get there. It’s important to think teleologically, even and especially if we feel stuck.

I don’t know whether David ever did that or not. The rest of David’s life as told in 2 Samuel seems to slip away from him in a series of misfortunes and challenges. It might be that it’s only with the benefit of hindsight that we can see the trajectory of his life and the way it was pointing, even if David himself might not have seen it. I’m not sure. But for those of us who are stuck in our own morasses or cycles of getting nowhere, I think we can learn from this passage. Our stories need endpoints, and our visions need teleology. We need to know where we are going, even if it's only onward, so that we will know how to move toward it. We need our horizons; we need visions of the future. Wherever you are right now, engage in the discipline of imagination, and think teleologically. Imagine your movement from here, and go.