A few nights ago, I woke up at about 2:00 a.m. and found myself unable to get back to sleep. That happens sometimes, and it happens more frequently as I get older. At first I tried to lie there and will myself back to sleep, which often works, but after a while I gave up and picked up my phone. I know that all the experts say that that’s the worst thing you can do if you want to get back to sleep, but I find that the light from the screen helps make my eyes tired, and I seem to get back to sleep quicker that way. I played the day’s Wordle (a tough day, I got it in 5) and Spelling Bee (I always stick to it until I get Genius), and then turned my attention to doomscrolling the news. Finally, I opened Instagram to see if anything was happening there.

Up at the top of Instagram I saw that my oldest kid had also been awake recently, posting a series of stories. One of them caught my eye; it was a screenshot of a news story about a flight that had been diverted to Denver after experiencing engine trouble. The plane landed and one of its engines caught fire; everyone escaped and there were only minor injuries. But my 17 year old teenager had seized the moment of breaking news to make a larger point about the current moment. “For those who don’t read the Bible,” she wrote, “we are living through the tribulation before the rapture.”

This surprised me for a few reasons. I did not know, for example, that she knew about the rapture (which she has never heard me or any other preacher at our church talk about), or that she counted herself among those who “read the Bible,” which I had never witnessed her doing in the wild. I quickly commented on the story, pointing out that the Bible mentions neither the tribulation nor the rapture (unless you kind of squint sideways at 1 Thessalonians 4), and that the whole scheme had been concocted only recently and popularized in my own lifetime in a series of fictional books. (It’s probably not much fun to have a Bible scholar for a dad). By the time I drifted off to sleep and woke up again in the morning, she had taken the post down.

I was surprised to see that post from my own kid, but I wasn’t really surprised to see it on Instagram. We are living through very intense and troubling times, after all, and people across the political spectrum have a way of making use of the Bible to bolster their own understandings of what’s going on in the world. I remember the experience of growing up during the Cold War in the 1980s, and seeing wild claims about Bible prophecies in supermarket tabloids. During the Gulf War in the 1990s and in the aftermath of 9/11, the Bible’s apocalyptic visions provided a way for a lot of people to talk about their own fear and anxiety. The pandemic brought out more popular biblical exegesis, only five years ago. So it’s not really surprising to see that people—including my own kid—are looking to biblical themes (even if the themes are not strictly biblical, in my opinion) to understand yet another turbulent period in world history. We are, after all, living in another one of those times of fear and uncertainty. From burning airplane engines to tariffs to seat-of-the-pants rearrangement of government to cascading climate change, things are dire out there. The Bible has some things to say about that kind of thing.

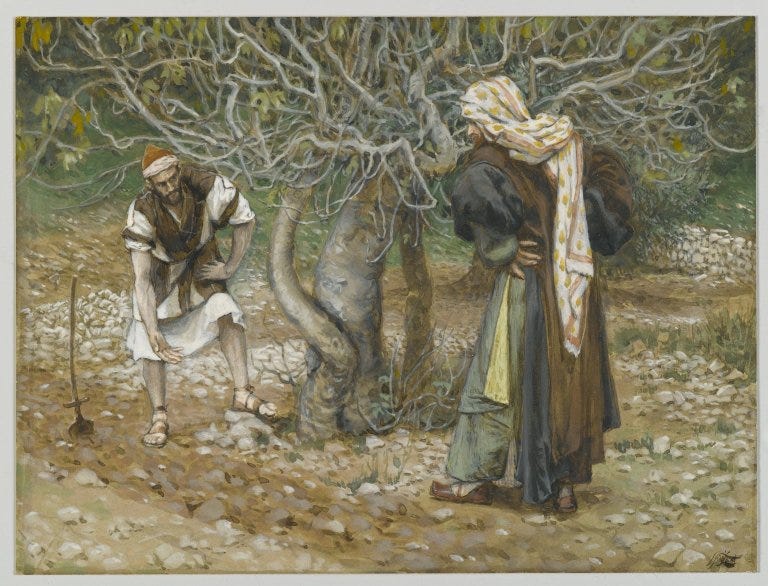

The gospel reading in the lectionary for this Sunday is one of those passages that people have looked to as a basis for their apocalyptic expectations. The parable of the fig tree is an apocalyptic parable, after all; it’s a dire tale of the dangers of fruitlessness and impatience. We can all be cut down, Jesus seems to be warning, if we are doing nothing more than wasting space.

But as I live through whatever we are living through, I find my attention drawn to the first part of this passage. Luke alone tells this story (although both Matthew and Mark have other fig tree passages); in the story, some folks tell Jesus about some current events. Apparently—according to the people present there with Jesus—the Roman governor Pilate had recently mingled the blood of some Galileans with the blood of the sacrifices they had been making—which implies that some violence was done to the Galileans as they were undertaking some of their religious practices in the temple, and maybe even that they were killed. It’s not entirely clear what this passage is referring to; there isn’t a historical record of anything like this happening, aside from this reference in Luke. But it also doesn’t seem to be totally out of character for Pilate (who had a bit of a reputation as a bloody ruler), or for Roman rule in the region generally, which like many exercises of power on the peripheries of empires could be brutal. The passage in Luke 13:1 feels kind of like the word-of-mouth news alerts that so many of us find ourselves giving and receiving all the time these days: “did you hear what they just said about Ukraine” or “did you see what DOGE just did?” In times of extraordinary weirdness and turmoil, we trade those little breaking-news anecdotes with each other, give each other dire and knowing looks, shake our heads in bewilderment, and then we get back to whatever mundane-in-comparison everyday task we were trying to complete.

Maybe that’s what the people in Luke 13:1 intended: to share an extraordinary bit of news with Jesus, build some rapport with him, and then move on with whatever teachings he had planned for that day. But Jesus seized on the news to make a point—maybe a different point than the one the people had expected. I think perhaps they had expected Jesus to seize on the stories of the injustice against the Galileans as evidence of imperial overreach, and they might have hoped that the news would help push Jesus toward some kind of open rebellion against Rome. Maybe they wanted to provoke and stoke outrage. But instead, Jesus took a much broader view, and he began to reflect on the vagaries and unfairness of life itself—the way bad things often happen to good people, and good things happen to bad people, and there isn’t always much correlation between the way we live and the way the universe visits blessings and curses upon us. Instead of taking the invitation to think of Pilate’s outrages against the Galileans as a pretext for rebellion, Jesus took the news as a way to think about how neither the Galileans nor another group of eighteen people who had been killed recently in a tower collapse had been especially sinful. Neither the Galileans nor the eighteen were “worse sinners” or “worse offenders” than anyone else, Jesus said, and yet they still met a bad end.

If I’m being honest, I’m not sure what to make of Jesus’ response here. Is Jesus saying that life is unfair? Point taken, but we knew that already. Is he trying to situate Pilate’s violence within a much bigger view of life’s uncertainties? Maybe. Is Jesus trying to somehow claim that the government’s oppressive violence is part of God’s retribution for sin? That’s the plainest reading of the text, but if that’s what he means, I’m not sure I can follow him there. Jesus’ response to this bit of breaking news seems disjointed and out of proportion, and it might even engage in some senseless blaming. And believe it or not, that’s why this passage from Luke strikes me as especially useful in the historical moment we’re living through right now.

The midnight Instagram post from my kid caught my attention because it was from my own kid, but it was otherwise pretty normal for the kinds of things I see online these days. I have friends across the political spectrum, and one of the things I have noticed over the last few months (and, frankly, over the past ten years or so) is that everyone is desperately trying to make sense of a senseless world. Everyone is trying to fit increasingly chaotic and nonsensical events into some scheme of meaning; everyone is trying to find a signal in the noise. I’ve noticed that whether you think Donald Trump is doing a good job or not, you’re probably still doing the same amount of work to figure out what it all means. Trump’s supporters and detractors are all busy constructing containers to put everything in, because without containers to put things in, everything is just too much, too confusing, and too strange. Whether you’re pro-Ukraine or pro-Russia, whether you’re pro-Israel or pro-Palestinian, whether you’re a techie or a Luddite, whether you’re an acolyte for free markets or a socialist, you’re probably working overtime to fit all the weird news and scary current events into some broader understanding of the world. That’s how we get from an airplane engine problem to the rapture: in a world that feels chaotic and uncontrollable, we try to find stories that connect things together, and if the connections aren’t there, we invent them.

Viewed in that light, I don’t think it’s so strange that Jesus’ mind jumped straight from Pilate’s latest outrage to a reflection about the vagaries of fate and an apocalyptic warning about the dangers of not being useful enough. Jesus, like the rest of us, was trying to make sense of the world. Like the rest of us, Jesus needed to find meaning in everyday events, even (or especially) if those everyday events were scary or ominous or nonsensical or unconnected to whatever else was going on. Like us, Jesus was trying to digest the daily news of an uncertain world, and he was trying to make it fit with what he already thought he knew. Jesus took a new data point—a new outrage from Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor—and he found a container for it. Others who heard the same news might have concluded that Pilate must be deposed, that Rome must be expelled, that people should avoid Jerusalem and the temple, that God must be angry, or that the apocalypse was near; there were all kinds of possible ways to make meaning from Pilate’s actions.

In the same way, there are all kinds of ways for us to make meaning from the events of the world today, and that’s part of the stressful incoherence that so many of us feel. You can look at what’s going on in the United States right now and conclude (as I do, for what it’s worth) that we are seeing the beginnings of a fascist regime. Or you could look at the same data and conclude, as many people do, that we are seeing the restoration of American power and prestige. Others might look at the same events and conclude that the conditions are right for pulling back on investments, or for building a backyard bunker, or for moving to Canada, or for buying some right-wing memecoin. We all try to make sense of new events by fitting them into some scheme of meaning; there’s something about our minds that won’t let the world be meaningless. And that’s how we jump from airplane engine malfunctions to the tribulation and rapture.

Maybe it’s comforting, then, to realize that people in the past did the same thing, and that even someone like Jesus had to digest breaking news and make sense of it on the fly as part of some greater scheme of meaning. Jesus heard about some political violence and needed to make sense of it, in a public setting, without much time to think it through. You know what, Jesus found himself saying, maybe it wasn’t fair, what happened to those people, but these kinds of things are never very fair, are they? And then Jesus found himself playing out an idea—a tangent, maybe—and only he could know how he had landed on it. This whole thing is like a fruitless fig tree. Sometimes the world feels like a tree that bears no good fruit, like a waste of the soil it’s planted in. If that’s what Jesus was saying, I think I understand his frustration, and I think I can follow him to his conclusions. If the whole thing feels fruitless, let’s try to nurture it, let’s dig around it and add some fertilizer and see if something grows. Let’s try one more time. And if that doesn’t work, we can always cut it down.

When everything feels fruitless, those can feel like the options. Hope and despair, creation and destruction, nurturing the tree or cutting it down, world-building or apocalypse. It’s interesting that when faced with those dichotomies, Jesus left room for both. Living through tumultuous times, we might also feel pulled in both directions. We also feel the urge to either leave room for growth or to cut it all down. Both can feel like reasonable responses to a fruitless world. The next time you’re lying sleepless in the night and you hear of some new horror—some 21st-century version of Pilate’s violence—ask the question posed by Jesus’ 1st-century parable. Is this a call for me to nurture something in the world? Or is this a call for me to cut it all down?

I wish I had seen this prior to Sunday! :)

I took a little different tack.

Interesting and provocative reflection on what makes the world go 'round. As I approach the terminal decade of my life, I have found that there are a few pretty well-defined buckets that hold much of what we know and observe about the universe. Most of those buckets have been defined by scientific inquiry--Newtonian mechanics, the laws of thermodynamics, the composition of matter (although we keep discovering more sub-atomic particles/forces), and some of the biological systems, for example. But when I try to predict or understand events that depend on human behavior, I have come to regard life on Earth as a random walk. Outcomes often bear no resemblance to the intentions or values of those who initiate the actions. The age-old question of "why bad things happen to good people" remains unanswered except by the theory of randomness. But even if you believe this worldview, that does not mean that we should simply avoid all efforts to effect outcomes. How can you look at starving children and turn away because that is just the way life is?