Perhaps you’ve heard of the Bechdel Test, which is a rubric for evaluating movies and works of fiction. The test, named for its originator Alison Bechdel, has a couple of different forms. The most basic form of the Bechdel Test is that to pass the test, a story must have two (or more) women in the story who have a conversation with each other that is not about a man. In the stricter form of the test, the women are also be required to be named characters. A surprising number of films fail this test; one database of about ten thousand films found that only 57% passed, which shows how frequently our stories fail to represent women and their relationality, and how often women’s stories are portrayed as centering on men.

The numbers are far worse if the Bechdel Test is applied to stories in the Bible. Although you can find people arguing that the Bible as a whole passes the Bechdel Test, the evidence for that is not very convincing to me. Some claim that the book of Ruth passes the test, since Ruth and Naomi have several conversations that are not explicitly about men. But I think that at a high level the plot of the book of Ruth is driven by concerns about marriage and procreation, so I am not really sure it passes. It probably shouldn’t surprise us that the Bible passes the Bechdel Test marginally or not at all; it was written by men (either fully or overwhelmingly, it’s hard to say for sure), and it reflects the various patriarchal cultures out of which it arose and was transmitted.

But of the Biblical stories that satisfy part of the Bechdel Test, the gospel reading for the fourth Sunday of Advent might come closest to satisfying the spirit of the Bechdel Test. The passage is Luke 1:39-55, which is the story of Mary’s journey to visit Elizabeth, Elizabeth’s exclamation about Mary’s blessedness, and Mary’s lyrical response, which we know as the Magnificat. This is the rare biblical story about two women, both of whom have names, who have a conversation with each other that is recorded in the biblical text. (If you aren’t sure why it’s remarkable that both Elizabeth and Mary are named characters, consider that in the Gospel of John Jesus’ mother goes unnamed; if you had only that gospel and not the others, you would not know Jesus’ mother’s name at all). In this passage from Luke, the two women share a conversation, but they are talking about a man—or more specifically, they are talking about the two boys in their wombs, and about a masculinized God who is described in the text as a strong provider. It doesn’t pass the test, but it comes close, so if we are grading on a curve set for the Bible, this story does pretty well.

This is a fun exercise, determining whether ancient passages pass modern tests, but it matters more than we might appreciate at first glance. We might be accustomed to the absence of women’s stories in the Bible, but they are strikingly absent. Where women do show up in the biblical text, their stories are often confined to experiences of violence and marginalization. The structure of Christian scripture excludes women and pushes them to the side, and the structure of the Revised Common Lectionary does little to correct the problem. Recently the Hebrew Bible scholar Wil Gafney has published The Women’s Lectionary, collecting women’s stories from the Bible and reading through the cracks and seams in the text to recover hidden and obscured narratives. Offering a “Year W” of readings that can replace one of the three years in the lectionary’s cycle, Gafney’s work is very worthwhile for people and churches who want to be intentional about centering women’s experiences. But for people who stick with the traditional RCL readings, the readings for the fourth Sunday of Advent are as good as it gets for finding an aperture through which to view the experiences of ancient women in the Jesus movement.

What do we find when we look through this story? I want to think about three major things that I see: the openness and possibilities suggested by the story, the limitations suggested by the story, and the kind of spiritual and political agenda found in the words of Mary.

First, the openness and possibilities. If the spirit of the Bechdel Test has something to do with the flourishing and joy of women when they are not being defined by or within the experiences of men, then this story has a lot to say. One of the remarkable things about this passage comes in verse 39, where Mary sets out to visit Elizabeth. More than a few of my students over the years have pointed out how this story seems to assume that Mary has the freedom to travel, seemingly independent of Joseph or any other man. She sets out, by all appearances of her own volition, to visit someone who seems to be dear to her. While it can be easy to imagine biblical women (or women in many other times and places) as sequestered and silenced, here we have a narrative in which a woman seeks out the company of another woman, undertaking travel to get there. That detail alone alerts the reader to Mary’s agency as a human being, and her ability to choose things for herself and curate her world.

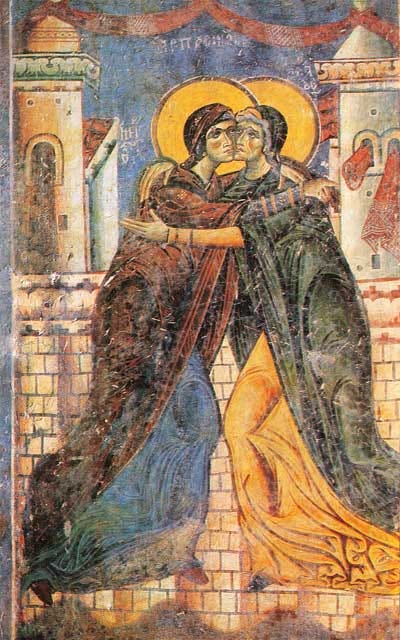

The scene of Mary and Elizabeth meeting each other is told through their shared experience of pregnancy, with Elizabeth’s child leaping in the womb at the approach of Mary’s child. You could say, then, that in some ways this is really a story about Jesus and John. But even across two millennia and several language barriers, I detect in this text a vibrant and durable joy—something ineffable passing between the two women that has found its way into the text despite all the barriers thrown up by patriarchy and misogyny. In this passage Elizabeth is described as being “filled with the Holy Spirit,” which the author of Luke (and Acts) reserves for the most important people and moments. Mary, too, is found rejoicing. Although in the author of Luke’s telling the women’s joy is directed toward their unborn children and toward God, I can’t help but think that it goes quite a bit deeper than that. In this story we get a glimpse of a kind of sociality and effusive community that doesn’t show up just anywhere, and we get a sense of these two women as people who have their own lives, desires, histories, anxieties, and deep loves, including a deep love for each other. Reading this passage feels a bit like being let in on a tender moment between two people who care deeply about each other and feel real joy in experiencing the joys of the other.

Second, though, I think this passage says something about the limitations that hemmed in (and still hem in) many experiences of womanhood. Although Mary’s song (the Magnificat) is often lifted up as an iconic moment of feminine expression, there are some difficult gendered dynamics to the way Mary describes herself. In verses 48 and 49, Mary uses strikingly self-denigrating language while also deflecting her own glory onto God. “For he has looked with favor on the lowly state of his servant,” the passage reads. The word “servant” there is translating the Greek doulē. That word (and its far more common masculine counterpart doulos) is usually translated as “servant” in modern translations, but I think it is probably almost always best translated “slave.” I understand why translations use “servant,” because that word softens the language quite a bit that makes it more palatable to religious audiences. But “servant” obscures the harshness of the power dynamics implied by “slave,” and it lets us off the hook of having to confront the ways logics of oppression are embedded in our theological language and our sacred texts. When Mary describes herself as God’s slave, she is referencing a whole system of bondage and oppression, and she is describing herself in a dramatically inferior language. Some interpreters even see room—in this word choice and in other narratives about Mary’s conception of Jesus—for asking questions about consent and reproductive choice. If Mary is describing herself as someone in an abjectly inferior position to God, as someone with no power or agency when compared to the Divine, then what possibility of consent or agency might have surrounded her pregnancy? In a time when reproductive choice is eroding in the United States and women’s agency is at a generational ebb, we can see some of our own anxieties and limits reflected in this story of Mary’s reproductive life. Even though she goes on to exclaim that she will be called blessed for generations (a prediction that has indeed come true), Mary chooses the language of enslavement and powerlessness to describe herself and her situation in relation to God. That tells us that whatever else might be true, Mary thought of herself as stuck on the underside of a stark power dynamic.

Third, and possibly relatedly, I want to focus on the theological and political agenda embedded in Mary’s words in 1:51-53. But first it’s worth mentioning a big caveat that applies here, and to the material above as well: it’s difficult or impossible to tease apart which words in the Magnificat belong to Mary and which ones belong to the author of the Gospel of Luke. This is true of all biblical texts; we don’t know whether or when the authors are using their own words or transmitting the historical words of one of their characters. But it’s especially true of the author of Luke. Among the gospel writers (and indeed among the biblical writers), the (anonymous) author of Luke is especially prone to write fancy speeches for his characters and have them say precisely what they should say in any moment. That’s especially obvious in the case of Mary’s speech that we call the Magnificat, because it’s modeled closely on Hannah’s song in 1 Samuel 2:1-10; the author is transparently drawing from tradition to frame Mary’s words. The chances are very good that these words are the author of Luke’s imagination of what Mary might have said in that moment, and not some historical transcript. I don’t think that should scandalize us; I think all gospel stories are working on some level of theological imagination, and I think that that’s a good thing. But it does mean that when we read or hear the Magnificat, we should imagine that we are hearing something from Mary, but that we are also hearing that voice mediated through the author of Luke and their (we don’t know their gender) understanding of what Mary might have said in that moment.

With that caveat aside, verses 51-53 are a remarkable manifesto of theological and political ideas. If we treat this passage as a transcript of a woman’s voice passed down to us from antiquity, then we should mourn that more women’s voices are not preserved, because the Magnificat is a powerful and compelling articulation of ethics and eschatology. Mary’s words here are worth reproducing in full. God “has shown strength with his arm,” she says. God “has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.” God “has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty.” What strikes me most about this passage is the way it focuses not on ethereal or abstract concerns, not on spirituality or salvation, but on material and embodied existence and the forms of injustice that come from living in bodies in the world. Mary imagines God as a scatterer of the proud, a deposer of powerful rulers, and a dismisser of the rich. Meanwhile God is also a lifter up of the lowly (undistinguished or subservient or abject or unable to cope, according to some of the definitions of the Greek word), a feeder of hungry people, and one who remembers and keeps promises. Mary speaks about justice in a clear and consistent voice here, and she’s unafraid to call out the injustices and inequities of her world (and ours). The Magnificat stands out in the Bible as an unusually clear statement about how the world ought to be, and that might be because the Magnificat stands out in the Bible as one of the few passages from the mouth of a woman. At the very least, I think we can tell where Jesus got his prophetic edge from.

As we encounter the Magnificat on the fourth Sunday of Advent, then, I think we can give thanks for Mary’s prophetic vision and for the effusive joy of both Mary and Elizabeth, even as we hold that gratitude alongside an awareness of how much their lives were limited and circumscribed by misogyny and gendered prejudice. We can marvel at this story, so powerful and overflowing with life, at the same time we mourn the rarity of stories like this in the Bible. We can be glad to encounter the story of two named women sharing a conversation, even as we notice how unusual it is for stories to be told this way—either in the ancient world or, apparently, in our own media today. But above all, I think we can listen—listen for the way Mary’s song reimagines the world, and listen for the way Elizabeth’s and Mary’s joy of being together points the way toward all the joy that is yet to come.

Thank you for your perspective on this text and for your comments more genmerally on the treatment of women in the stories of he Bible.

Mary & Elizabeth recognized they had agency. Both were prophetic! Bechdell Test! Thank you for bringing light to this beloved passage in new ways Doc!❤️