There’s an archetype, in works of fiction like films and books, of the special and wise seer—the one who is set apart by their perception, their powers, their knowledge, or their abilities. Think of Yoda (or just about any Jedi), or Gandalf, or Dumbledore, or Picard. Think of literary figures like Lauren in Octavia Butler’s novel The Parable of the Sower, or Whatsit, Who, and Which in A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. These figures are sometimes called the “Wise Old Man” figure, or the Senex, in Jungian psychology—though of course they do not have to be men, and they don’t even have to be old. This figure is a person who has achieved enough status and wisdom and power to help others along their ways. And that’s often just how they show up in a narrative—as someone who appears at a critical moment to offer special insight, power, help, or advice.

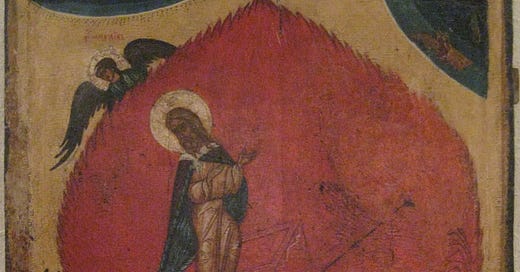

In thinking about two of the stories from the lectionary readings for February 11th—which is Transfiguration Sunday—I was noticing how much they participate in and rely on the Senex trope. This is one of the benefits of juxtaposing texts together, like the lectionary does; it helps you see themes and patterns in the readings together that you would not have been able to see as easily in each of them apart. The reading from 2 Kings 2:1-12, in which Elijah’s ministry ends and Elisha’s begins, appears in the lectionary readings alongside Mark 9:2-9, in which Jesus takes three disciples up the mountain to witness his transfiguration. Separately, these two passages come from very different time periods, and very different parts of the Bible. But they share a few key themes and details in common:

· Both stories involve appearances or expressions of the divine,

· Both stories involve Elijah,

· Both stories involve the bestowal or confirmation of special power or status.

In a way, these two stories of Elijah’s ministry ending and Jesus’ transfiguration give us a view of the Senex, the wise old man, at a few different points in that archetype’s arc. In the 2 Kings reading, we really have two Senexes (I’m not sure how to pluralize that word). Both Elijah and Elisha are archetypes of wisdom and divine knowledge. Elijah is at the height of his powers, at the end of his career, about to be taken off to heaven in a chariot. And Elisha is the apprentice, who is still just starting out and learning, but who is about to inherit the role—and a double portion of it, at that. Elisha is about to become a wise figure, but he is not one yet. Elijah is the wise figure, but he’s about to depart from the world. It’s a succession story, with the one giving way to the other.

If Elisha is at the beginning of his Senex arc, and Elijah is at the end, Jesus at his transfiguration is right in the middle. This story comes just slightly after the midpoint of the gospel, after Jesus is established in the way that Elisha is about to be established, but before Jesus leaves the world in the way Elijah is about to leave it. So, together these two stories, show us how a wise figure might have their origins, reach their potential and come into their power, and then depart from the world.

What does it mean to think of Jesus as a Wise Old Man figure? In some ways, he’s not a great fit for the role. Jesus is the main character, for one thing; the Senex is usually more of a secondary character or a helper to the hero. And Jesus is out front and visible, as opposed to the Senex who is usually working in the background, helping out behind the scenes. But if we think of Jesus in this mold, as a person who has special powers and special knowledge, then it helps to make sense of his characterization in the gospels—the way he is developed as a character in the story. It makes sense of some of the milestones that the gospels tell us about—how he showed flashes of wisdom early on (in Luke’s gospel), how he was baptized by John (all four gospels), how he was reluctant to perform a sign before it was his time (John 2, the wedding at Cana), and how he came into the fullness of his power and glory at this moment, the Transfiguration, which is told in the Synoptic gospels. Those milestones are showing the reader how Jesus is coming into his own, gradually embodying his identity, becoming who he is bit by bit. It helps make sense of Jesus’ beginnings.

Thinking of Jesus as a Wise Old Man figure also helps with how we think about the end of Jesus’ story—the part that parallels Elijah’s narrative. Jesus, as a Senex, foresees his own death, and he predicts it. He prepares for it, wrestles with it, and accepts it. In the gospels’ scenes of Jesus on the cross, we see a variety of ways of understanding what Jesus was thinking. In Mark, Jesus seems uncertain, to a degree, and pained. In John, Jesus is supremely confident and calm. In Matthew and Luke, he is still dispensing wisdom and interacting with the thieves being crucified beside him. Different gospels show Jesus embodying his role in different ways as he approaches death, with the gospel of John having the most similarity to the way Elijah was shown in 2 Kings: calm, confident, knowing exactly what will happen next, in control the whole time.

When we view Jesus’ life and career as an arc like this, of the origins, development, and embodiment of the Senex archetype, the Transfiguration story becomes a moment of crystallization, a moment of recognition, and a moment of achievement of a special status. The Transfiguration becomes the story of how Jesus came to be Jesus—how he arrived at last as the full embodiment of the Christ role, recognized alongside Moses and Elijah and affirmed by God.