It’s inauguration week in America.

Inaugurations are curious things. They are celebrations of individuals—revelries devoted to the person who is being installed in a high office. But more than that, inaugurations are centered on institutions and their perseverance. An inauguration marks a moment when the players have changed but the stage has remained, a time when the singers are different but the song is the same. We do inaugurations for the people being inaugurated, but I think we really do them as an expression of institutional persistence. We’re still here, inaugurations say, doing a new thing, again.

Trump’s second inauguration will be my twelfth presidential inauguration, if my math is right, although I wasn’t old enough to pay much attention to the ceremonies for Reagan or the elder Bush. The first inauguration I can remember clearly was Clinton’s first, which I recall mostly for Maya Angelou’s poem and a breathless sense of optimism. I felt that again in Obama’s first inauguration, which I watched, tears welling up, live-streamed in a common room of the graduate school I was attending. (Perhaps you can discern my politics). Other inaugurations I have watched wincing, afraid of what they would bring, studying words and postures and small acts for evidence of whether and how things would turn toward something sinister. In my professional life, I have also had occasion to attend various other kinds of inaugurations: inaugurations of presidents at theological schools, installations of Deans, appointments of clergy into called and covenanted roles. Every time, it was a celebration of the individual, draped over a much broader affirmation of an institution’s durability.

I’m writing this only hours before Donald Trump’s second inauguration, which seems likely to test that pattern. If most inaugurations are an exclamation point in institutional history, Trump’s hand on the Bible represents something more like a question mark. Does his ascendancy represent continuity with the past or an end to it? Will he perpetuate institutions or wind them down or hollow them out? Trump’s enemies and allies alike understand him as a disjunction in history, as an interruption to the cycles of government we have come to expect. For his enemies, that’s the threat he represents, and for his allies and his supporters, that’s Trump’s value proposition. He has promised to intervene in normalcy, which is why many people fear him and why many people voted for him.

Jesus’ visit to the synagogue of Nazareth in Luke 4:14-21 was not quite an inauguration, but it was inaugural. It wasn’t a ceremony meant to install power and position in a person like a modern inauguration is, but it does function—a least within the narrative of Luke—as a kind of ritual moment for celebrating both Jesus as a person and the whole range of religious and cultural systems that surrounded him in that moment. The story takes place in a synagogue, which at that time was a center of activities that we might variously call religious, ethnic, and cultural. This particular synagogue was located in Nazareth, a place with a lot of familiarity and importance for Jesus—his hometown. And the ritual moment, the reading of a text in community, was a recitation of communal history. (Luke seems to have a preference for citing Isaiah in important moments relating to the history of Israel and the story of the Jesus movement—in the story of John the Baptist, in this story, in the story of the Ethiopian eunuch, and in Paul’s words in the closing verses of Acts’ last chapter). If we read Jesus’ words in Luke 4:14-21 as an inaugural address, some things stand out. He's using someone else’s words here—the words of the prophet Isaiah—but Jesus is also claiming them in a way, and he’s saying that the words are “fulfilled” in the way they had been heard by the people gathered there that day. Jesus, then, was using this citation from Isaiah as a kind of inaugural roadmap, offered at the beginning of his ministry, pointing the way forward.

This way of citing the past to speak about the future is a fixture at inaugural events. American presidents often cite the nation’s history and its founding values at their inaugurations, as a way to point forward to the next four years in office. We have always been this way, goes a common inaugural framing, so we now pledge to be this way more urgently in the years ahead. The inaugurations I have witnessed in church and in the academy work in a similar way, calling people back to first and founding principles as a way to gesture to an uncertain future. We’re still here, doing a new thing, again. It’s a powerful way to signify a moment like an inauguration, pointing to the past as a way to speak a future into being.

This week—and Monday in particular—holds more significance in our civic calendar than the inauguration alone. Monday is also Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Many churches will have already celebrated that day on Sunday the 19th, but I expect that the twinned events of Trump’s inauguration and MLK Day will create unexpected and strange resonances throughout the week. It’s easy to contrast the visions of the two men, though in recent years some on the right have sought to claim King’s ideas and legacy for themselves. In some ways, Trump’s base is centered on rolling back some of the initiatives put forward by King, and Trump’s policies seek to unravel a moral vision that King helped stitched together.

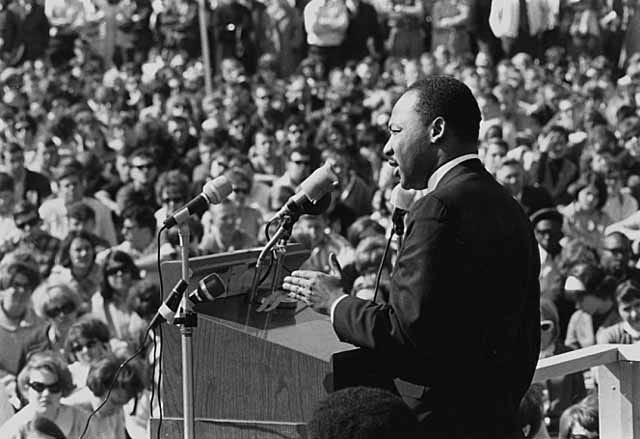

Often on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I find myself thinking about my favorite of King’s speeches, the one called Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence, which was delivered as a sermon in 1967 at the Riverside Church in New York. This video offers an 8-minute selection from the longer sermon, and it points to a set of moral issues that King had come to understand as connected:

In this selection from his speech, as in the speech as a whole, King is engaging in a kind of inaugural moment. He is inaugurating a new era in his career—an era in which he began to expand his advocacy beyond civil rights as it had been traditionally understood and into questions of poverty and violence. This speech marks the entry of King into the discourse around the Vietnam War, but more than that into the tensions he saw underlying the conflict: “a society gone mad on war.” You can hear King, in this speech, harkening back to first principles, in the call to “recapture the revolutionary spirit,” and in his “disappointment” with America. As King reminds us, “there can be no great disappointment where there is no great love,” and in this speech King speaks out of his great love and into a possible future in which poverty, racism, and militarism do not collude against America’s originary promise. “There comes a time when silence is betrayal,” King announced, and those words would have made sense on Jesus’ lips too, as he announced to the synagogue in Nazareth, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set free those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” It is a coincidence, but maybe a coincidence brought on by a shared frame of mind, that both Jesus and King mark their inaugural moments with citations of Isaiah. Jesus cites the 61st chapter in the quote above, and King cites the 2nd chapter at the end of the clip above: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

People were angry about King’s speech, just like (in verses 28 and 29 after the lectionary cuts off the reading) the people of Nazareth were angry about Jesus’ speech. “No prophet is accepted in the prophet’s hometown,” Jesus said, and the same sentiment applied to King. King is nearly universally lauded today as an American visionary, prophet, and hero, but after his Beyond Vietnam speech he was attacked in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and even the NAACP, and he lost support from people like Lyndon B. Johnson and Billy Graham. The more time King spent pointing out the connections of poverty and violence to America’s ongoing racism and denial of civil rights, the less support he could expect to receive from the American political and religious establishments.

My special interest in King’s Beyond Vietnam speech comes from my tangential connection to it. The speech was written by the civil right activist and scholar Vincent Harding, who taught for decades at the school where I now teach. When I was a graduate student there, Harding’s office was on the ground floor of the student housing building where we lived, and he would often greet us and our toddler as we played in the grass or the snow. Harding wrote the speech as a young man, but it already held a number of the themes and commitments that would come to characterize the rest of his career: peacemaking, nonviolence, and a vision of an America that had not yet come into being. It’s this last thing—Harding’s vision of a yet-unborn America—that has most captivated me. I had the chance to hear Harding speak a couple of times before his death about a decade ago, and I was always drawn in by his way of speaking to the not-yet-ness of America. Here’s a short clip of an interview with Harding at a conference a couple of years before his death:

Quoting Langston Hughes, Harding speaks to the not-yet-ness of America as an idea: “America never was America to me, And yet I swear this oath-- America will be!” Here, Harding is reversing the move that many inaugurations make. Instead of we’re still here, doing a new thing, again, Harding (and Hughes) is longing for the moment when we begin doing the thing we have said we would do all along. Inaugurations focus on what has been; Harding’s framing so often focused on what might yet be. Instead of claiming that something has been fulfilled in your hearing, as Jesus claims, Harding keeps our ears attuned to the future, to the unfolding of a country that does not yet exist, to a horizon beyond which we have not yet been able to move.

I don’t think we will hear anything like Harding’s words or King’s words during this inauguration week in America, and I don’t think we will hear anything like Jesus’ words either. I say that not because I lack all faith in Donald Trump (though I do lack all faith in him), but because America has turned against the moral vision of King’s Beyond Vietnam speech, and because America seems to have given up on Harding’s idea of the nation as a promise coming into being. America, for all its pretensions to Christianity, cannot even embrace Jesus’ citation of the prophet Isaiah; a platform of good news to the poor, release to captives, good health care, and liberation from oppression would be crushed in either of today’s major political parties. We chase war and profit the same as we did in King’s day, but with more fervor and tighter knots of theological logic.

There’s a poignancy in noticing the hollowness of that word fulfilled in Luke 4:21. The past tense is mocking. The captives are still captive, the poor are still poor, the blind are denied treatment, and the oppressed grow in number, twenty centuries after Jesus stood up in the synagogue. In the same way, the Vietnam War raged on for nearly a decade after King’s speech, and exactly one year after he gave the Beyond Vietnam speech in New York, Martin Luther King Jr. lay dead in Memphis. We are left, then, to do what Jesus did in the synagogue: to pick up the words of our traditions, words from the prophets who went before us, and to renew their vigor for a new time and place. We are left to take up the visions of Harding and King and (newly, as if for the first time) Jesus, and to recite them in a new moment. We are left to inaugurate—to still be here, doing a new thing, again—the world that still so desperately needs to emerge.