We’ve been on a run of kinship-talk on this Substack lately, discussing both the wonderful aspects of belonging and the ways it can turn sour. Kinship can provide a welcoming and nurturing home in which people can flourish, and it can also be a toxic cage from which people struggle to escape. The story of Jacob laboring seven years first for one wife and then another, tricked by his kinsman Laban, illustrates the double-edged way that kinship is often portrayed in biblical texts, and Joseph’s treatment at the hands of his brothers—a story continued in the lectionary this week—reminds us that not all forms of belonging are life-giving.

But beyond the ways kinship works from the inside, there is another dimension to it—the ways kinship functions as a logic for relating to other people who hold and participate in different forms of belonging. Not only do we contend with our own systems of belonging, but we bump into other people’s belonging too, coming up against groups and systems to which we do not belong. The biblical text is absolutely full of these kinds of stories—tales of how this or that group got its start, or etiologies of why these or those enemy peoples became so depraved. Sometimes, when people-groups like this are in view in the bible, they are recognizable as what we would call ethnicities, or at least clans or tribes. Today, we have added a category that didn’t work in quite the same way in the ancient world, race, that can help us think about these texts too, even though it’s anachronistic. Ethnicity, clan, tribe, and race are all ways to talk about difference, both to describe difference and to pathologize it—to explain difference in terms of why different people are different, and sometimes why (the text thinks) we should think of them as bad and wrong.

The past several weeks I have been traveling, and I bought an audiobook to accompany me on my trip. The book was one I had been meaning to read for a while, The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. It traces the history of the Great Migration of African-Americans from the South to the North of the United States in the first two-thirds or so of the 20th century. I absolutely recommend this book to you, if you haven’t read it; I am still captivated by the stories she told, and I find myself thinking about it all the time. But as you might imagine, one of the persistent themes and claims of the book is that one of the major root causes of the migration—stronger than economic necessarily, kinship bonds, ties to the land and culture, or anything else—was the abuse of the Jim Crow system. Yes, the Great Migration was prompted by economic factors, as many have argued. And yes, it sometimes flowed in family systems. But more than anything else, the six million or so migrants from the South to the North were fleeing the terrors of Jim Crow. (Wilkerson makes this point throughout, but especially in her afterword, where she points out research that shows that specific acts of violence (lynchings) in one region would often lead to an exodus of African-American people from that particular place). Perhaps that shouldn’t surprise us, but it seems that research has often hidden that motivation under economic ones, imagining that it was only higher pay that was driving people out of the South. Instead, as Wilkerson and others demonstrate, it was the systematic dehumanization and violence of post-Reconstruction southern life that led so many people to flee the only places they had ever known and take their chances in northern cities.

Jim Crow is an ethnic logic—or, as we might say in our modern contexts, a racial one. It’s a way of reckoning one group of people in the eyes of another group, and a way of organizing society accordingly. Jim Crow (and the modern forms of racism that are related to it and grow out of it) works by creating an Other out of a group, making sure that the Other is and remains external to one’s own group, and policing the boundaries between the groups with the utmost vigilance. So, in the Jim Crow South, there always had to be strict boundaries between Black and White people—a system of apartheid—so that the logic of racial or ethnic discrimination would not get confused, and would be continually maintained and reinforced. One of the big themes of Wilkerson’s book is that the kinds of racial (or racist) logics that were found in the South were also found in all of the Northern and Western cities to which the Great Migration flowed. There might have been a difference in degree of severity, but there was no difference in kind. Housing discrimination, employment discrimination, education discrimination, and other forms of racial boundary-policing were (and are) as prevalent in cities like Los Angeles and New York and Chicago as they were in the rural South. They were—are—simply hidden under more layers of politeness and deniability. I have noticed, as a southerner living in the West, that my adopted hometown of Denver is as segregated as anywhere I ever lived in the South, or more so—a condition that Wilkerson’s book helped me understand in all of its historical complexity.

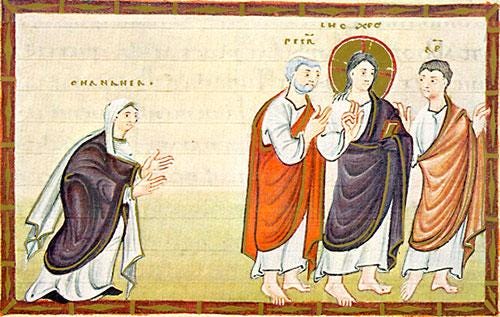

In the gospel text in this week’s lectionary, we see a form of ethnic logic that we might say belongs to the same species as Jim Crow, although of course there are vast differences in time and place and severity. This is not an indictment of Jesus or of the Jewish milieu of which he was a part; it is simply a recognition that like most or all societies, there was a way of reckoning insiders and outsiders, selves and Others, kin and enemies. In this text, Matthew 15:22-28, we get to witness a meeting between Jesus and a woman described as a “Canaanite” from the region of Tyre and Sidon. This is a neighboring area, and Jesus was on her home turf, but right away the text alerts us that the difference in belonging—a difference in what we might call ethnicity—is important to the story. This story reminds me of other stories like it in the New Testament. Mark 7:24-30 has a parallel version to this story (in which the woman is a gentile of Syrophoenician origin), but it’s also reminiscent of the encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4 and Paul’s meeting with the enslaved girl in Acts 16, among others. In these moments in the New Testament where Jesus or someone else encounters someone from a different ethnic group, the rest of the story often proceeds along the lines of ethnic difference, with their interactions inflected by the tensions introduced by the boundaries between them. Remarkably, in these stories, the protagonists in the story (like Jesus and Paul) do not come off very well. In this story in Matthew, Jesus at first ignores the woman, and then says, out loud, that he was not sent to her or for her. “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel,” he said, as a way of rejecting her entreaty. Then, as if to drive home the viciousness of Jesus’ point, he says that “it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.”

Many commenters have pointed out the meanness and dismissiveness in Jesus’ words here. He is limiting his mission to Israel alone, and thereby excluding the woman in front of him, and her daughter, from the purview of his work. He’s also calling her and her daughter “dogs,” and many commenters have noted that the Greek word in 15:26 and 27 is a diminutive and derogatory form of the word “dog,” and that it might be best translated into English not as “dog” but as “bitch,” to capture the insult held in the Greek word. That translation isn’t going to make its way into English versions anytime soon, but it’s worth keeping in mind as we read this story. Jesus was not speaking or acting in any heroic way in this story, and he was certainly not doing right by this Canaanite woman.

Instead, Jesus was policing a boundary. He was operating with the ethnic logics of his own time and place, working hard to keep himself and this woman on opposite sides of an invisible line. Notably, the woman accepts his logic; she is accustomed to being thought of in this way, and she seems to anticipate it. “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table,” she says. There’s a bit of wordplay to her response that’s not visible in English; the words “Lord” early in the verse and “master” late in it are both the same word in Greek: kyrios, the word for a landowner, head of household, slaveholder, or other important man. (There is a female form of the word, but it only appears a couple of times in the New Testament, both in the 2 John). So the language that modern Christians might read in English as a theological acknowledgement by the woman of Jesus’ lordship, when she says “Yes, Lord,” might actually simply be her deferential language, responding to Jesus’ harshness and trying to get around it to achieve a good result for her daughter. She might not be calling “Lord,” but “sir,” or even “master,” in a display of passivity. That possibility ought to trouble us, and make us question what we think we know about Jesus, which is reason enough to entertain it.

Jesus’ response was emphatic: “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” The daughter was healed. I’ve heard this passage preached sometimes as an example of this Canaanite woman convincing Jesus, showing him by the shrewdness of her response that she was a worthy recipient of his ministry. I think there’s truth to that. But I also wonder whether it would have read that way to people steeped in the boundaries that Jesus and this woman were speaking across. Would their conversation have sounded like a victory for the woman, meant to humble Jesus and teach him something about the proper scope of his ministry? Or would it have sounded like the woman fitting into her place, addressing Jesus with genuflection, and appealing to a certain noblesse oblige on his part? I don’t know. It’s an unsettling story for that reason; the power dynamics are strong, but it’s not quite clear where they start or end, or where Jesus and the woman see each other in them.

This story depends on a whole history of interactions between Canaanites and Judeans, both historical and literary. The past shows up in their exchange, unavoidable and obvious. Jesus and the woman represent things, to themselves and to each other, and the story of their conversation depends on those representations. We don’t fully understand all of them; none of us have ever either been or met an ancient Canaanite or an ancient Judean, and we don’t bring the same kinds of things to the story that ancient readers would have brought. We do, however, bring our own modern prejudices and histories—our own ethnic and racial logics—and we read the story with and into those understandings. In that sense, the invisible boundaries, subtle Othering, and fiercely enforced separations in this story from Matthew can speak into our own lives. If we are uncomfortable with Jesus’ dismissive and elitist attitude in this story, then that discomfort should tell us something about ourselves. If we are offended by him calling her and her daughter dogs—or bitches, even—then we should be able to find plenty in our own world to offend us too. As I’ve said before in this Substack, the text isn’t a window, it’s a mirror. It doesn’t let us see some other time and place, like looking through a portal. It lets us see ourselves, and sometimes we won’t like what we see.

Thank you for this. It makes so much sense the way you articulate it! I’m grateful.