I started seminary in the fall of 2000, just as the anxiety and panic of Y2K was subsiding, and just before the anxiety and panic of 9/11 began—and exactly in the middle of the anxiety and panic of the disputed 2000 presidential election. It felt like apocalyptic times—one of several such moments I have lived through now—and it was an auspicious but nerve-wracking time to be undertaking theological education.

I had an old Jeep SUV then, with north of 200,000 miles and enough cosmetic and minor mechanical issues to keep me taking it to the shop, but never anything major enough to let me down when I really needed it. I remember taking it one day to a mechanic shop on West End, not far from campus, where I was making small talk with the guy who would be fixing my clunky driveshaft. When he found out that I was working on a degree at the Divinity School, his eyes lit up. “Do you think we are living through the end times,” he asked? “It seems like the signs are all there.” He told me that he had been reading the Left Behind series, which was all the rage in those days, and like many people he was worked up about the possibilities that events were in motion that would bring about the tribulation, the antichrist, the rapture, and the end of the world. I told him that I had not read any of the Left Behind books, but that they were fiction and not very much related to any biblical texts that I knew about. He seemed like he remained suspicious, like he wanted to hang on to the possibility that Al Gore really might bring about a secular New Age one world government that would make us all wear barcode microchips, but he had me sign some paperwork and he got started on my Jeep. (The driveshaft never really was right again).

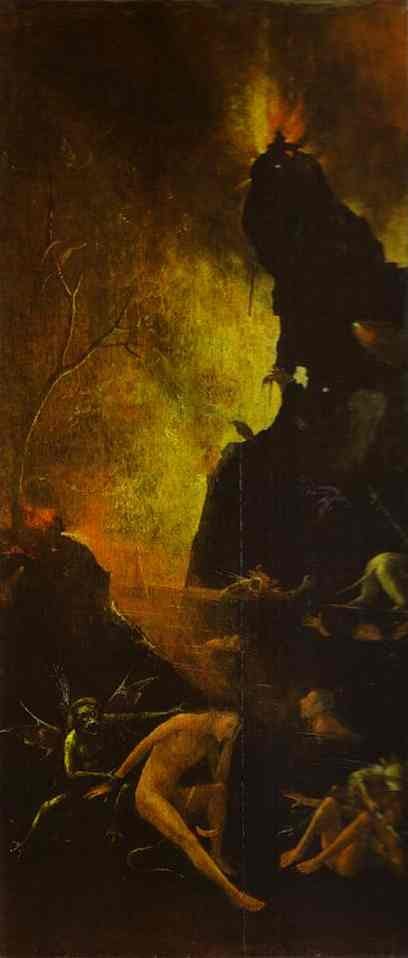

I’ve had a hundred different variations of that conversation over the last couple of decades, and although that one sticks out, they all run together. Sometimes the biggest emotion in those conversations is excitement or curiosity, but most often it is fear. People often tell me about the trauma of being 6 or 8 years old, lying awake at night in fear of being left behind in the rapture. They talk about the scare tactics of churches and youth pastors who would speculate about the horrors of society’s collapse, of Satan’s 1000-year reign, or of being left parentless in a disintegrating world. People tell me about things they have noticed in the news—something to do with Israel, or the United Nations, or Iraq—and they want to know if I think it’s a sign of the end of days. Often these are people who have long since left their childhood churches, or sometimes even all religion altogether, but fear still seizes them whenever they think about the idea of living through the apocalypse, and they still take for granted that the Bible predicts nothing but terror at the end of the world.

One of the first things to say about the Bible is that it does not really contain any scenario that’s anything like the ones those people are afraid of, and certainly nothing like what the (fictional) Left Behind books or any other apocalyptic account might envision. The claims of dispensationalists and rapture-hawkers and fiction authors are far, far, far more clear and confident than the biblical evidence they purport to rely on. The case for apocalypticism is made mostly by cherry-picking verses or even phrases from across the Bible, from unrelated books, then taking them out of context to make it seem like they relate to each other. Take something from Daniel, a vague scary phrase from Revelation, something Paul wrote to some folks he knew, and a description of some war that ended thousands of years ago, and claim that it’s all about the stuff you’re seeing on CNN, and you’ll probably get some attention and maybe even some followers. But you won’t be doing responsible biblical interpretation.

The lectionary readings for November 12th are tricky, because they contain some of the passages that get used to justify these scary apocalyptic fantasies. They’re tricky because while most clergy have had enough seminary Bible classes to know that modern apocalyptic readings of ancient biblical texts are not very solid, many people in the pews—even well-read and well-informed people—have more exposure to the cultural misuse of Christian apocalypticism than they do to responsible readings of these passages. So when someone stands up in church and reads something like 1 Thessalonians 4, Amos 5, or Matthew 25, people might hear it as a validation of what amount to theological conspiracy theories. Because of that, it takes some care and tact to preach or teach texts like those.

Matthew’s reading is a parable of ten bridesmaids—five wise, and five foolish. It’s a parable about preparation and readiness; the foolish bridesmaids did not think to bring oil for their lamps, but the wise bridesmaids did. The wise bridesmaids refused to share, and while the foolish ones were off buying oil, the doors to the wedding banquet were shut, and the foolish bridesmaids were locked out. The bridegroom, strangely, refused to let them in, saying that he did not know them, and the parable ends with the admonition to “keep awake therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour.” The parable often gets read as an apocalyptic warning from Jesus—a warning to be prepared for things to come. But it also raises questions about the kind of God Jesus represents, if God is the bridegroom in this parable: one who is capricious, forgetful, and not open to the pleas of people who have been wrongfully shut out.

The passage from 1 Thessalonians is somewhat famous, because it is the closest thing we have to a biblical reference to anything like the “rapture.” The rapture is not a biblical concept, really; it is not found in Revelation where you might expect it, and the word itself is not found in most English translations. The concept derives more from evangelical and dispensationalist fantasy than anything else, but here in 1 Thessalonians we find the raw materials of that fantasy. 1 Thessalonians is probably the earliest of Paul’s letters that we still have, and therefore the earliest book in the New Testament, dating to perhaps 49 or 50. Because it is so early, it’s a valuable window into some of the interests and anxieties of earliest Christianity, when the first generation of Jesus’ followers was still living. The background of this letter from Paul is probably that the people of the church in Thessaloniki, a city in Macedonia or northern Greece, had heard Paul’s preaching when he was there and had come to join the Christian movement. But in the time since Paul left them, something had happened that was shaking their understanding of Paul’s preaching. Paul, it seems, had left them with the impression that Jesus’ return was immanent, and that they should await his return as the moment of their salvation. (It’s easy to see where Paul might have gotten that idea, if he had heard about sayings of Jesus like the Matthew 25 parable above). But then, in Thessaloniki, people had begun to pass away, and that provoked a lot of alarm in the community. Had Jesus’ return been delayed? Had Jesus failed to come back at all? But mostly, the Thessalonians were seized with a specific fear: Would those people who had died miss out on salvation? In his reply, we can see Paul doing eschatology on the fly, in response to the questions the Thessalonians had asked him. Paul, too, was probably surprised by the delay of Jesus’ return, and in the letter he is working hard to explain it. Jesus is still returning, Paul reassures them, and when he does the ones who have died will rise first. And then, he tells them, the people still alive will be “caught up in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air,” which is where people get the idea of “the rapture.” (Notice that Paul in this passage still expects this to happen in his lifetime, and in the lifetime of the people living in Thessaloniki: “we who are alive, who are left,” will be the ones caught up in the clouds).

The passage from Amos, meanwhile, is famous for being an apocalyptic text, but it’s probably more famous because of its use by Martin Luther King, Jr., as a key passage about justice. That last part, 5:24, is hard for me to read without hearing King’s voice: “But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an everflowing stream.” The earlier part of the passage, though, is concerned with what Amos is calling “the day of the LORD,” which “is darkness, not light,” and which ought to be feared and not longed for, according to the prophet. It’s not completely clear what “the day of the LORD” might have meant, historically, to Amos; this is one of the earliest references to it, and Amos doesn’t stop to explain what it is. But it seems clear that some people had been looking forward to that day, and Amos thinks that it is foolish to do so. Perhaps it was a calendar day, like a holiday; that help to make sense of why Amos then goes on to say that God hates festivals and solemn assemblies. Or maybe it was a hoped-for day in which God would intervene in history on behalf of Israel. But whatever it was, Amos is warning people not to look forward to it, because it will be terrible.

These three passages are some of the dozens that get used in the construction of apocalyptic scenarios, as part of a Christian industry devoted to doing just that. I can remember, as a teenager, going to a Christian bookstore that I liked, and having to walk past the sale tables outside the store to get inside. The sale tables were lined with books that argued for the end of the world. Some claimed that the world would end last year; those were 50% off. Some claimed that the world would end ten years ago; you could get those for even cheaper. Inside, you could buy books claiming that the world would end this year or even next year, but after walking past the outdated ones, I was never very tempted to pick up one of the new ones. It turns out that even if the people making the predictions are doing it sincerely, the main effect of their efforts is to sell books. And they have been wrong every single time.

That doesn’t keep their predictions from being scary, though. If I think back to all of those conversations I have had with people over the years, and all the fear that came to the surface in talking about the “end of days” or the apocalypse, it makes it harder to simply dismiss all of it as evangelical fear-mongering or book-selling. Right now, with the war between Hamas and Israel, the old cottage industry of identifying signposts along the road to the apocalypse has sprung back up in full force. People are asking, again, whether we are living in the end of days. Hearing these texts come up in the lectionary will probably make some people feel even more afraid, because they will hear the texts as one more data point in an increasingly scary world. It might be, for some people, the way it is described in Amos 5:19: “as if someone went into the house and rested a hand against the wall, and was bitten by a snake.” It might be that some people encounter these readings not as a comforting shelter but as a threat.

If we are doing responsible biblical interpretation, what would that look like? I think it begins with pointing out that the scenarios that have caused so much fear in people’s minds are not really biblical, but that they are products of a 20th-century theological agenda and an attempt to sell books. A lot of what makes people afraid is part of a fictional world; we shouldn’t be any more afraid of “the rapture” or being “left behind” than we should be afraid of Voldemort or Sauron. Likewise, all the conspiracy theories about what role modern nation-states and cultural trends might play in the end times are part of a counter-cultural project of 20th-century evangelicalism; they were manufactured by people who wanted to oppose certain aspects of society (like science, for example, and institutions like the United Nations), and who created apocalyptic theologies to attain that goal. Once we have debunked those things—which are many of the reasons many people are afraid—we can begin to read these texts for what they are, within their time and place and from the standpoint of our time and place. Jesus’ parable of the bridesmaids becomes a story about preparation and readiness, a beguiling story about being caught out on the wrong side of things. 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 becomes a tender pastoral moment, in which Paul is trying to respond to the anxieties and fears of people he feels responsible for. Amos 5:18-24 becomes less about God’s wrath, and more about the prophetic call for justice and righteousness that Amos and all the prophets (up to and including Martin Luther King, Jr.) have called for. Once you take these passages out of the artificial structure of evangelical apocalyptic theology, they aren’t scary anymore at all. They are, once more, a wall you can rest yourself against, without fear of being bitten.