(If you prefer to listen to this post as a podcast, click here.)

Vanity, the Teacher of Ecclesiastes insists. Everything is vanity.

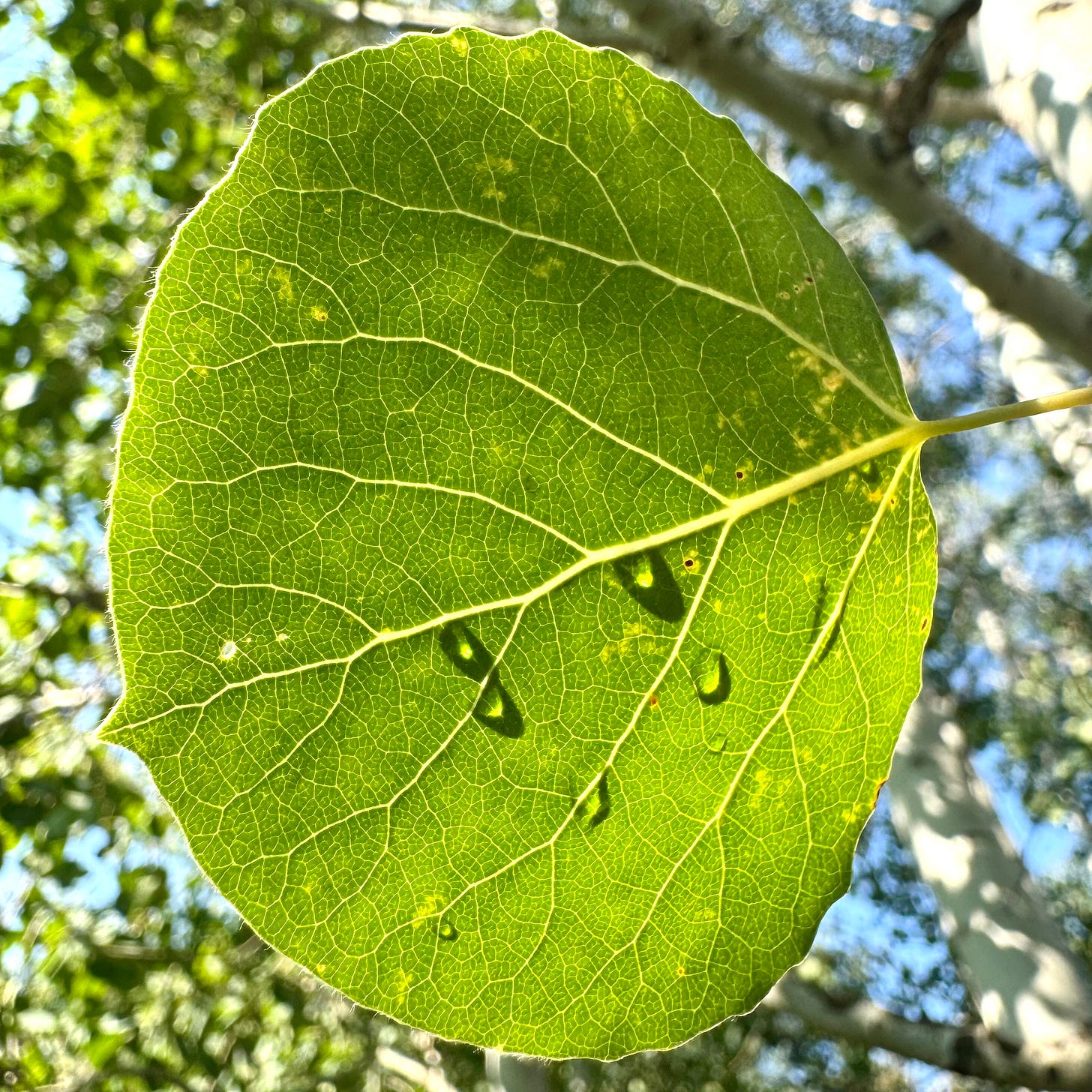

It’s a hard word to translate, this Hebrew word in Ecclesiastes 1:2. The language there is shifty and hard to pin down in English. The dictionaries suggest vapor, breath, worthlessness, casting about for a word slippery enough to translate the Hebrew. Many translations use vanity, but just as many others use meaningless. One of those gimmicky translations that tries to put things into everyday English uses perfectly pointless. Nonsense, offers another, useless, says one, and The Message—which I loathe for the way it so frequently loses the plot in its attempts to be clever—The Message uses smoke.

Today is another smoky summer day in Denver. This summer isn’t as bad as the summers sometimes are. The smoke wafts in and out of the atmosphere over the city, and this summer it hasn’t lingered the way it sometimes does. This year the smoke is coming from a fire in Arizona, the weatherman says, so it’s fresher and more aromatic, almost evocative, like a campfire. In many years the smoke comes from farther away—from fires burning in the Pacific Northwest or in Canada or California—and it arrives to Colorado stale and stagnant and soaking into everything. Some years the smoke settles over the city in a haze and stays there, for days or weeks at a time, and Denver’s air quality can be among the worst in the world. On those days, even healthy people have to stay inside. And sometimes the smoke comes from fires much closer to home, blazes burning in the foothills of the Rockies that you can see glowing red against the sky from the city at night, and the gray air brings a certain kind of panic—a realization that we are all just a few shifting winds away from losing everything.

Wildfires in the West—and everywhere else, it seems—are becoming more frequent, more destructive, and scarier. There are a bunch of reasons for that—reasons like development of land that used to be wild, and fire policy that has emphasized prevention and suppression and extinguishment, so that fuel builds up to catastrophic levels. But most scientists agree that climate change is playing a huge role in the increase in fires. Precipitation patterns are changing, and areas that were once wetter are now drier. Most of the West is in the grips of a long drought, and many other parts of the country are too. The snow melts off the mountains earlier now, which keeps the land drier for longer, and of course there’s the heat. The hotter the weather, the more likely fires become, as the vegetation dries out and the world turns into a tinderbox.

There’s nothing to anything, goes The Message’s overwrought translation of Ecclesiastes 1:2. It’s all smoke.

Where I live in Colorado, wildfires and drought and heat are the most obvious signs of climate change. But elsewhere, the world is going haywire in other ways. Last fall in western North Carolina, my mother spent weeks and weeks trapped in her house without power or water after Hurricane Helene washed out all the roads and bridges and wrecked a whole region. Over a hundred people died in floods and landslides and treefalls. Hurricanes have always swept up into the mountains and caused flooding in the steep terrain, but the storms come more often now, and they are stronger than they used to be. On the beach in North Carolina where we vacation sometimes, every year the sea rises by about a half an inch and every year fifteen feet of beach erodes away. It’s noticeable now, even though the Army Corps of Engineers pumps sand from the seafloor back up onto the beach nearly every winter at a cost of millions of dollars, to try to keep the beaches as broad as they once were and to keep the oceanfront houses from falling into the sea. In many places around the world, every summer is now the hottest one on record, and if it's not, it’s in the top five. And in a lot of places it doesn’t snow anymore.

Ecclesiastes—which is in the Revised Common Lectionary’s readings for August 3rd—is a pessimistic book. Tradition has it that Solomon wrote it in his old age, though there isn’t much evidence of that, and the book attributes itself to someone called the Teacher, or Qoholet in the Hebrew. This Teacher speaks in a world-weary voice—a voice full of both wisdom and resignation. Life has taught the Teacher about the meaninglessness of things, the impermanence of the world, and the vanity of human industry and effort. It is a book about the unhappy business that God has given to humans to be busy with, as it says, the chasing after the wind that consumes our lives, as the Teacher puts it.

What do mortals get from all the toil and strain with which they toil under the sun, asks Ecclesiastes 2:22-23? For all their days are full of pain, and their work is a vexation; even at night their minds do not rest. This also is vanity. It’s a grim perspective on things. You can tell that the Teacher of Ecclesiastes carries a lifetime of sorrow in his voice, the kind of accumulated exhaustion and grief that can begin to settle into the air around you like smoke, getting into everything, the kind of resigned and weary tired that catches up with so many of us, sooner or later, piling up with age.

Sometimes these days it’s not the oldest among us who lack hope, but the youngest. As the parent of three teenagers and as someone who runs a church youth group on the side, I spend a fair amount of time around young people, and I have been eyewitness to a strengthening trend. Eco-pessimism, some people call it, or climate pessimism—the idea that the climate crisis is so bad that there is no hope. (When I googled these phrases to see which ones deserved a hyphen, Google helpfully suggested alternative search terms. It suggested that I search for the phrase humanity has no future).

Today’s young people have grown up in a world in which three things have always been true. First, for them it has always been true that the science has been settled on climate change. Second, for their whole lives the consequences of climate change have become ever more visible, in floods and wildfires and heat waves and hurricanes and droughts. And third, for them it has always been true that the world’s leaders (and especially the leaders of the United States) and the world’s industries have been utterly feckless and disingenuous and dishonest and useless about taking action on climate. Many of the world’s most prominent figures deny that the climate is changing at all, or they deny that humans have anything to do with it, or they deny that it would be worthwhile for us to change our behaviors. Some of the world’s most prominent capitalists launch token PR stunts that gesture toward climate action while they lobby government to be allowed to pollute more. Some launch rockets, having concluded that at this point Mars is a better bet than Earth.

The young people I know have paid attention to all of this, and like the Teacher of Ecclesiastes, they have long since rid themselves of any naivete about the nature of their reality. They don’t make a lot of space for hope. They are leaning into the vanity, the meaninglessness, the vapor and the smoke. Many of the teenagers I have known over the last couple of decades have told me, matter-of-factly, that they do not expect to grow old. Most of them, these days, consider it a moral error to have children; most of them think it is an ethical failing to bring a child into a rapidly disintegrating world. Hidden behind that sentiment is an implicit criticism of their own parents; many of the young people I know resent having been brought into a world so compromised and reeling. But it’s not just anecdotes; a recent study found that 16% of American adults, and a larger percentage of younger adults, experience psychological distress because of climate change. Many people, especially young people, experience clinically-detectable depression and anxiety because of the deteriorating state of our planet.

It is never a good idea to apply modern categories to ancient people, and it’s never smart to diagnose anybody through a book, but the author of Ecclesiastes seems a little anxious and depressed, too. Maybe more depressed than anxious. Even just in this passage that the lectionary gives us for Sunday, the Teacher finds several kinds of lament. It is an unhappy business that God has given humans to be busy with, you might recall him saying, and then he calls all the deeds that are done under the sun so many forms of vanity and chasing after the wind. I turned, this Teacher writes, and gave my heart up to despair.

I have been interested for a while now in debates over whether despair is ever the right response to anything. I have a colleague who wrote a book called Embracing Hopelessness, and the argument is pretty much what it sounds like. I have found the book fairly convincing. But on the other hand, I have also been convinced by those who point out that hope is not really about what you expect to happen in the future, but it is an orientation toward possibility. Hope, they say, is a pointing toward a horizon, or a way of creating a horizon, if there isn’t yet one to point to. In the world of climate change, hope doesn’t mean that we pretend that everything is going to be ok. Everything is manifestly not going to be ok. But hope, they point out, is the best indicator of action. If we are hopeless, then we will do nothing, because—obviously—there is no hope. But if we have hope, even if it is a hopeless hope, then we will act in accordance with that hope. In this way of seeing things, climate pessimism or eco-pessimism become forms of climate denial, indistinguishable from the climate denial of certain politicians and political parties and CEOs. Eco-pessimists and climate deniers come at things from different angles, but both of them end up arguing for doing nothing. Better to have hope and do something, than to sit back and wait to die.

There’s an interesting idea in Ecclesiastes 2:21. It comes right after the part where the Teacher gave his heart up to despair. After that, the Teacher of Ecclesiastes makes a good observation. Sometimes the one who has toiled with wisdom and knowledge and skill must leave all to be enjoyed by another who did not toil for it, he writes, adding, this also is vanity and a great evil. In other words, we never labor only for ourselves. The Teacher calls this a great evil, but I am not so sure. It’s a great evil if you view the individual in isolation and if you assume that you only ever labor for yourself. In that way of seeing things, it is unjust for someone to come after you and enjoy the better world you’ve made. But if you recognize that we inherit the world and that we also pass the world on as an inheritance, then it isn’t evil at all, to work to make it better, and it certainly isn’t vanity to leave it better than you found it.

I’m old enough to get where the Teacher is coming from. It’s hard to grow older, to watch grief pile up, to see loss accumulate and to see labor come to nothing. The world has a way of wearing all your enthusiasm thin and bittering your heart. And I’m young enough to get where America’s young people are coming from. It’s distressing to inherit a world that has been treated so carelessly and dishonestly, and to imagine growing up amid so much vanity and meaninglessness and vapor and smoke. So very often, pessimism feels like the right response and hope feels foolish.

I wonder then about a middle path. I wonder how to see the world for what it is and also to work to make it better. I wonder if there’s a place for all our grief and loss and ash and smoke alongside our hope and hard work and maybe even optimism.

I wonder if there is a way to live in the world as it is, and at the same time live in the world as it might yet come to be. I wonder if there’s a way to live as if the world were not all smoke.

Programming note: Join me in a live chat on Friday August 1st at 12pm Mountain Time (2pm Eastern, 1pm Central, 11am Pacific) for a discussion of this and other texts for Sunday!

Thoughtful post. I like the book hopeful pessimism discussed on Sean Illing’s podcast