I spent the last week in an intense bout of teaching. Three weeks out of the year, all the hybrid students at the school where I teach come to campus for some residential classroom time. Both of my courses this quarter are hybrid courses, which meant that last week I spent sixteen hours teaching across four days. One of the common themes across both courses was the question of how Christianity coalesced as a movement and a social structure—how the impromptu crowds of people who followed Jesus around somehow transformed into a “church” with networked structures of theologies, practices, and relationships. Students are always interested in the question of how much the Jesus movement belonged to broader cultures, and how much it stood out from everything else around it. They are always curious about how Christianity created structure and order, and how those forms of organization changed things. Students often want to know what early followers of Jesus thought they were doing and what they thought they were creating, and they often ask how the choices made in the first few centuries of Christianity continue to reverberate today.

The lectionary readings for this week offer an interesting glimpse into the ways Jesus became a movement and that movement became a church. If you have ever watched crystals form, with structures appearing seemingly out of nowhere to create intricate patterns, then you might see something similar happening in some of this week’s lectionary readings. The New Testament doesn’t tell the whole story of how Jesus’ life and teachings crystallized into the religion we know today, but it does give us peeks at moments when we can see it happening. And while some of the structures we know today took a long time to develop, some of them were visible very early on.

Take, for example, the gospel reading for this week, which is John 10:22-30. This passage is vintage John, with many of the hallmarks of John’s gospel. We see Jesus in Jerusalem, in the temple, talking with “the Jews,” which is John’s characteristically vague (and vaguely menacing) way of referring to Jesus’ conversation partners. We see “the Jews” questioning Jesus—fervently and sincerely and hopefully, to my mind—about whether Jesus considered himself to have been the Messiah. We see Jesus responding in a cagey and perhaps even haughty way, which fits really well with Jesus’ self-presentation in the Gospel of John. And we see an emphatic declaration of Christology and theology—“the Father and I are one”—that leaves little doubt about who Jesus considered himself to be.

The really interesting image in this John passage, I think, is shepherding. Most of us don’t spend much time with shepherding as a practice, or with sheep as living beings. Sheep and shepherding, for many modern readers, are abstractions—a literary trope or a metaphor. We talk about shepherding a project to completion, or how a teacher might shepherd her class to recess, but we likely don’t spend much time in the day-to-day maintenance of a herd of sheep. It’s interesting, then, to ask what we might miss in this passage that ancient readers would have heard. When Jesus talks about “my sheep,” what kind of ownership and responsibility is he implying? When Jesus claims that “I give them eternal life,” what might that mean, and when he promises that “no one will snatch them out of my hand,” what sort of leadership model is he imagining?

I don’t pretend to know much about sheep or shepherding—I’m definitely one of those modern people who lacks knowledge or experience with herding of any kind—but I do think this passage and this metaphor tell us something important about how early followers of Jesus thought about him. Whoever wrote the Gospel of John (and I’m partial to the idea that John was written by a community that coalesced around the “disciple whom Jesus loved”) thought it was important to use a metaphor for Jesus that implied intense, absolute care for insiders (the herd) and something bordering on disregard for outsiders (the ones who “do not belong to my sheep”). It seems that at least in the community that gave rise to the Gospel of John, Jesus was not for everyone, and the church did not have porous boundaries. Jesus was the shepherd of one flock, and at least in this passage from John 10, other sheep in other flocks simply could not expect any kind of relationship with the shepherd. But for the ones in his flock, Jesus’ protection was absolute.

If we jump to the lectionary passage from Revelation 7:9-17, though, things get messier. Revelation is a famously confusing and convoluted text, but I think it’s one of the most useful sources for understanding how early Christians saw themselves as part of a larger world. In this passage, Jesus is both Lamb and shepherd; he is both victim and protector. Many modern Christians struggle with the violence and gore that comes with the language of blood, but passages like this one remind us that blood and bloodiness were powerful symbols in the early church. In this passage (as well as an earlier one in chapter 6) we get a vision of martyrs in the throne room of heaven. The martyrs were the “great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples, and languages,” who were the ones “who have come out of the great ordeal.” The martyrs were in heaven, praising God.

This scene deserves a little bit of unpacking, because it might run counter to modern Christian expectations. Today, many Christians imagine that people who die go directly to heaven (or to hell) to be with God (or not). But in the early church, many or most Christians believed that people who died stayed in the grave and awaited the second coming and the general resurrection of the dead, when all would be judged. (This is what’s behind the famous passage from Paul, in 1 Thessalonians 4, where he’s comforting people and reassuring them that the ones who had died had not missed out on resurrection and salvation). Far from being crowded, early Christians imagined heaven as somewhat empty—at least temporarily—as everyone awaited the resurrection. But there was an exception to that, and it shows up here in Revelation 7 and also in chapter 6. If you died as a martyr—as someone who was killed because of your faith—then you could expect to go straight to heaven and live under the altar there. That’s where this multitude comes from; they were the martyrs who had died for their faith and had been transported to heaven to praise God.

But that raises some questions about “the Lamb,” who is a central figure in Revelation, and about what it means to call the Lamb the “shepherd” of the flock of martyrs. Is the Lamb Jesus, who is something like the first among the martyrs? Is that why his blood is able to wash garments white, in 7:14? The image of blood making something white is intentionally paradoxical, but there’s a greater paradox also embedded in the text: what kind of shepherd ends up with a flock of sheep who have been killed because of their association with the shepherd? The metaphor of shepherding almost folds in on itself here, becoming impossibly convoluted. Jesus is a slaughtered and bleeding Lamb but also a shepherd; Jesus is a shepherd of a flock for which the promise of John 10:28, “no one will snatch them out of my hand,” has not come true, or perhaps has come true in a truly unexpected way. One gets the sense, reading through Revelation 7, that these paradoxes did not bother the author of Revelation very much. Revelation seems to think that these martyrs have all found a happy ending. But I’m left thinking about shepherding and wondering how this particular shepherd could be thought of as successful. Was Jesus—the Lamb—a successful shepherd because his flock ended up in heaven? Or was he a failure, since his flock had all been murdered along the way? For the community that was reading and interpreting Revelation, and imagining their place in the broader world, belonging to Jesus and belonging with Jesus might mean being rejected by the rest of the world, even to the point of death. It’s a stark vision of insiders and outsiders, such that even ordinary Christians—the ones who had not been martyred—were left on the outside looking in, waiting in their graves for the resurrection when they would be able to attain what the true flock had already received.

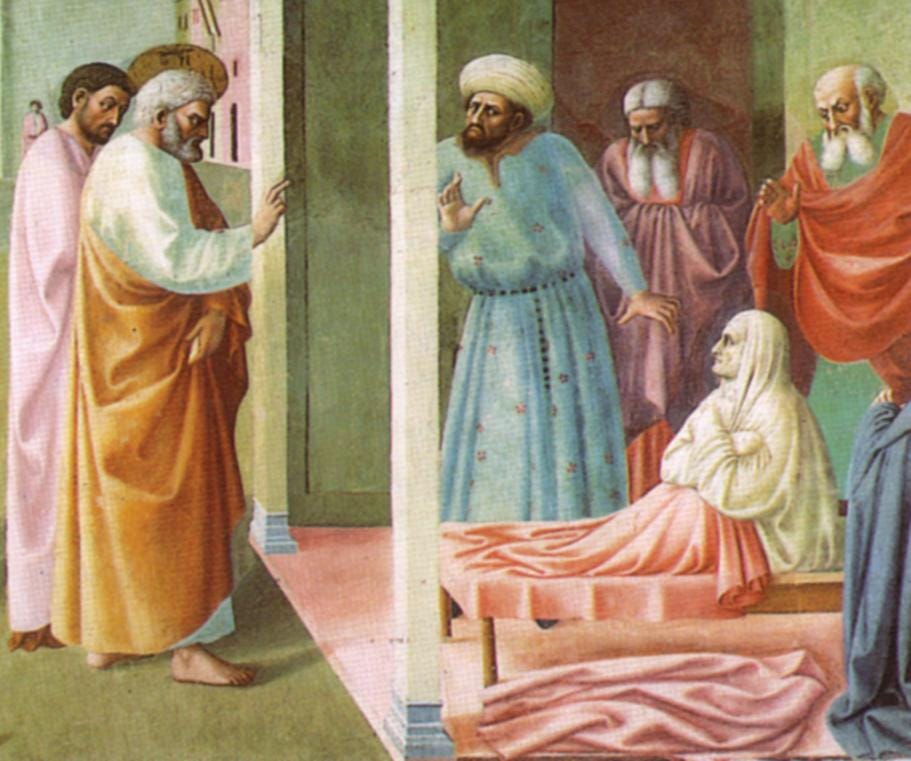

If Revelation gives us valuable insights into the ways early Christians organized their worlds and their thoughts, Acts offers even more of a window into how early Christians thought of themselves and what they thought they were up to. In the passage from the lectionary this week, Acts 9:36-43, we find Peter in Lydda and we pick up the story of a woman named Tabitha (or Dorcas) a few towns over in Joppa. (Tabitha and Dorcas both mean “Gazelle,” in Aramaic and Greek, respectively). Scholars point out that this story bears some resemblance to other stories of raising the dead found in the New Testament, especially, the story of the synagogue leader’s daughter found in the synoptic gospels and the story of Lazarus in John. It’s a delayed-raising story in which the dramatic tension is ratcheted up by distance and time; by the time Peter arrived in Joppa, the woman had been dead for a while. Much like those stories of Jesus raising the synagogue leader’s daughter and Lazarus, the delay in Peter’s arrival only serves to emphasize the miracle. (I think there are also interesting parallels to the story of the raising of Eutychus by Paul in Acts 20, though in that case there was no delay).

I don’t want to focus on the raising itself, though, but on what this passage tells us about how the early Jesus-followers were crystallizing into the networks and structures that would eventually become the church. There are a few things to pay attention to here. First, notice how Tabitha is described: as a disciple. This is the only use of the feminine version of the word for a disciple in the whole New Testament, though there are other places where women like Mary Magdalene are described in disciple-like ways, and there are places (mostly in Paul) where women are called by other prestigious titles of leadership. The use of the title disciple for Tabitha here points to a usage of that word in a more generalized sense, beyond “the twelve” and the inside-circle connotations of that usage. It might tell us that disciple had become a way to talk about adherents to the movement, or that disciple described some special role for Tabitha in the Jesus-following community in Joppa.

Some scholars point to verse 39, with its reference to “all the widows,” to understand what might have been meant by Tabitha’s discipleship. It’s a thin thing to rest an argument on, but the use of the definite article in that phrase, “all the widows,” might mean that the community in Joppa had a class or order of widows to which Tabitha might have belonged. This kind of thing was certainly true of later Christianity, which often had formalized groups of widows who acted as a unit and shared certain practices, including charity and sometimes celibacy. It’s possible that Acts 9:39 is an early reference to those groups, and that Tabitha was a member of such a group, and that that’s the sense in which she was a disciple. If so, that might make sense of the details about Tabitha’s “good works and acts of charity,” and her clothing-making work, in verses 36 and 39. It might have been that Tabitha’s particular form of service to the community and the world was to sew clothing for people who would not have otherwise had access. Again, this is all based on pretty thin textual evidence, but scholars can point to the fact that these kinds of structures existed later on in Christianity, and hypothesize that this passage gives us an early glimpse of them.

Beyond the specifics of Tabitha’s story, this passage also gestures toward the crystallizing networks and structures of the Jesus movement, at the moment it was beginning to become something more solid. The group in Joppa (who are described as “the disciples”) sent for Peter, who was nearby. That tells us that there was enough organization in Joppa that some kind of leadership group could spring into action in a crisis and act on behalf of the whole, and that there was enough connection that they would have known that Peter was a few towns over, and that they could have sent for him and reasonably expect him to respond. Peter, for his part, had enough prominence that his whereabouts were known and understood even by people in different parts of the movement. And notice how, in verse 43, Peter then goes on to stay in the home of a tanner named Simon. One begins to get a sense that there was an informal but sprawling network of Jesus-followers, linked by loose but durable bonds, that could be activated in times of need, whether that need was the death of a disciple or somewhere for Peter to stay.

Thinking back to the lectionary readings from the Gospel of John and from Revelation, and the way those passages were describing life for insiders to the tradition, we can begin to get a sense of how these early Jesus-followers lived their lives and organized themselves. The promises of a shepherd—as someone who keeps tabs on the sheep and protects them—were being fulfilled not in specific actions by Jesus himself, but by the actions of the communities that sprung up in his name. Where the Gospel of John had Jesus describe himself as a shepherd, and Revelation imagines Jesus as both Lamb and shepherd, the passage from Acts 9 describes the community itself as fulfilling the role of protector and guide. The thing that Jesus promised about himself in John was taking shape in Acts as the actions of a community. The protection that Revelation and John imagine as a shepherd’s work is, by the time of Acts, happening in networks of Jesus-followers that are beginning to look ever-so-slightly like a church. No doubt the disciples in Joppa would have pointed back to Jesus as the true shepherd of their community; no doubt they would have credited Jesus as the real protector of the flock. But even by the time of Acts, written perhaps in the late first century, it was the community, the network, the growing crystallized peoplehood that came to be known as the church, that was offering safety and sufficiency to the people.

I thoroughly enjoyed the reference to crystallization. Nice visual.

Thank you.