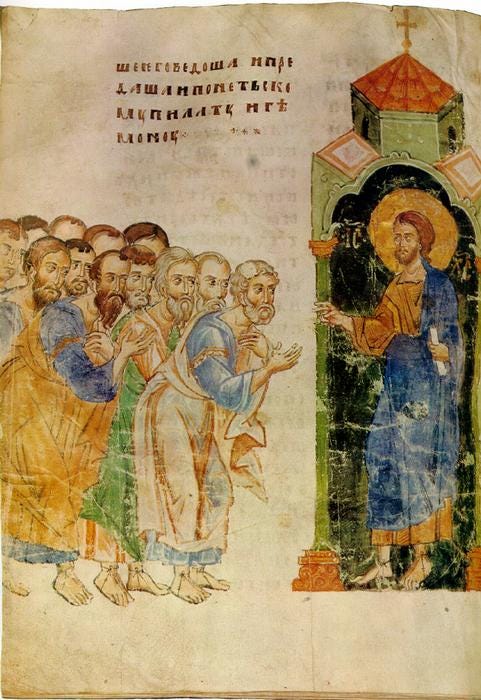

“And looking at those who sat around him, he said, Here are my mother and my brothers!”

With that line, found in Mark 3:34, Jesus does something important and radical: he makes identity about belonging, he makes kinship about community, and he makes family about love.

These words from Jesus are found near the end of the gospel text in the lectionary for June 9th. They were spoken by Jesus in response to a series of challenges. First, a crowd gathered around Jesus so thick that it was difficult even to eat. Then, Jesus’ biological family tried to rein him in, feeling that he had gone too far, that the crowd around him had grown too large, and perhaps that “he has gone out of his mind,” as it says in Mark 3:21. After that some learned scribes from Jerusalem challenged Jesus, accusing him of working hand in hand with demons. Then finally, Jesus’ family again came to him, making another attempt to pull him out of the crowd and out of view of the bigwigs from Jerusalem. Someone told Jesus that they were looking for him: “Your mothers and your brothers and sisters are outside, asking for you.” And that is when Jesus looked around him and realized that he was already at the center of a very large family. “Who are my mother and my brothers,” he asked rhetorically, gesturing to the crowd. “Here are my mother and my brothers!”

One of the remarkable things about queer theory is that it reaches in so many directions at once. (Some readers may be uncomfortable with the word “queer,” remembering its use as a slur, but that is the accepted and dominant umbrella term for the intellectual sphere that brings questions of gender and sexuality to bear). Queer theory thinks about persons and their relationships, of course. This is the “love who you love” side of things. It also thinks a lot about identity, in the “be who you are” sense. But there’s more to it than that, some of which we will get to in the weeks to come. For now, though, one more: queer theory is the primary place where interdisciplinary conversations about norms and normativity are happening—where scholars and theorists are thinking about how our lives are structured by norms and by either adhering to them, breaking them, or “queering” them. (You should check out the great Substack from a friend of mine, Matthew David Morris, about the ways the norms of heteronormativity get in the way of churches succeeding in the full acceptance they claim to offer). These all come together in this passage from Mark, and queer biblical interpretation can help us read it with new insight.

All of us know about families. We all have different experiences of family—both lived and idealized. We know, culturally, what families are supposed to look like; we have seen idealized families on television and in movies, and perhaps we have even seen models of ideal families in action when we have observed friends and strangers. Certainly we have all received strong social messaging about what families ought to be like, and perhaps we have felt guilty when we have been unable to measure up to that. That’s because our lived experiences of family are often really different from those ideal visions. Families are supposed to be wholesome, nurturing, loving, and safe, but they can sometimes be none of those things, and even the best families are always imperfectly living out the ideals. The lived experiences of LGBTQia+ people bear this out. Queer people can feel rejection or misunderstanding from family, and those experiences of outsider-ness can be especially hurtful from a structure like a family that is (socially and culturally) supposed to provide the ultimate in insider-ness.

This all has to do with norms and normativity. We all live with norms, all the time, and we all know what it’s like to conform to norms and to violate them. When we think about those idealized families that our culture wants us to aspire to and idolize, a bunch of normativities pop up. Those idealized families are nearly always heteronormative, for example: a man, a woman, 2.5 kids, and a dog. They are patriarchal, usually, with a strong role for the paterfamilias—another kind of norm. In our culture in North America, idealized families are racially normalized as white, which can be expressed in a lot of different ways.

I’ve been watching the third season of Bridgerton this past week, and one of the most disorienting things about that show is that its premise is that one major norm (white supremacy) has been abolished, so that people of all ethnicities and races intermarry without giving it a second thought. But all other norms—ones based in gender, class, power, and sexuality—are preserved as if the show were historical fiction. It strains the imagination to think that a society could simply decree race as defunct, while also preserving a stark caste system with Lords and Ladies at the top and servants at the bottom. We all know that our norms are too interlaced and interconnected for a world like that. And Bridgerton, and the society it portrays, is shot through with norms and normativities. The characters on the screen are always kvetching about whether they ought to be speaking together, for example, given the social prohibitions to doing so, and the consequences for being caught. Perhaps our modern real-world norms (and our families) are not so rigidly structured, but we do live with some of the same anxieties about keeping up appearances and conforming to unattainable ideals.

Jesus’ mother and siblings are feeling some of that pressure in Mark 3:20-35. Jesus, after all, was not conforming to norms very well. Ancient norms were not the same as our modern norms, of course, but even modern readers can see where Mary’s anxieties might come from. Her son was drawing huge crowds that followed him everywhere, and he was attracting the attention of important people—educated people from the big city—who were accusing him of being in league with the devil. Much has been made of Jesus’ seeming non-normative singleness; many people have questioned whether a first-century Jewish person in his late 20s or early 30s could have been unmarried. But even sidestepping that fraught debate, there’s a lot for Jesus’ biological family to worry about. Most kids from Nazareth were settled down and running the family farm or fishing business by then; Jesus was out there stirring up mobs. “He has gone out of his mind,” some people were saying in 3:21, and we should probably take that seriously as something that a lot of people were saying about Jesus. Jesus’ mother and siblings were worried.

A lot of us probably know what it’s like to worry about family members and to be worried about by family members. There’s a level of that kind of meddling that’s pretty common. (“Why can’t you come home for Christmas?,” “When are you going to have a baby?,” “What kind of job do you expect to get with a major in Russian literature?”). But LGBTQia+ folks often report even more fraught relationships with family. We probably all know people who have been outright rejected by their families for their sexuality, or who have endured years or decades of being frozen out or excluded. Some have lived through the ostracization and pain that comes from being queer in a non-affirming family (or even sometimes in an affirming family), and constantly bumping up against norms that are impossible to live up to.

One of the most deeply embedded family norms is that biology ought to be a controlling factor. You owe something powerful to blood relationships, the thinking goes, and shared genetics should probably dictate shared interests, commitments, and social performances. We all know that this is both true and untrue in different measures; we all know that it’s possible feel affinity with biologically related people, and we all know that it’s possible to feel distance from the people who are our closest biological relations. Being genetically related to someone can be powerful, both in positive and negative ways, and the norms that privilege belonging along biological lines can be difficult for some people to fulfill.

Because of that, human beings have been making family in non-biological ways for a long time. Sociologists call this “fictive kinship,” when we use the language of family to describe people who are not our biological relatives. Often, we use a warmer phrase: chosen family. This is a tactic that many people use across lots of different contexts. For example, Greek organizations use the language of brother and sister to describe membership, and Christian churches have done the same since antiquity. (One of the earliest biases against followers of Jesus was that they were incestuous; they went around calling each other “brother” and “sister” and then greeted each other with a kiss, and outsiders didn’t grasp that the language of kinship was fictive). We might describe a close friend as “a brother from another mother” or “a sister from another mister.” I am an uncle to a kid who is not biologically related to me, and my kids have a lot of aunties who don’t share any unusual amount of DNA with them.

This dynamic comes crashing together in this story from the Gospel of Mark. Jesus’ biological family seemed to be staking a claim to Jesus’ behavior that was rooted in adherence to norms; they were trying to coerce him back into line. They felt that his behavior of drawing large crowds and tussling with religious authorities was transgressive; even if it wasn’t breaking any laws, it was certainly violating norms. So they were following him around, trying to talk to him, trying to pull him back into behaviors that were more aligned with what was expected. Jesus’ biological family’s intentions were probably good, and they almost certainly thought that they were doing the right thing for themselves and for Jesus. They thought that everything would be better, for them and for Jesus, if Jesus could just toe the line a little better, and conform a little more clearly to the expectations of society. Maybe there are some queer folks who can relate to Jesus’ experience of a well-meaning biological family doing a lot of harm by repeatedly trying to pull him back in line with norms and expectations.

But Jesus saw through it, and he diagnosed immediately what was happening. The gospels have a few stories like this one—stories and sayings in which Jesus denies the importance of biological family—so many that there is a body of biblical scholarship devoted to analyzing those stories and their themes. In this one, Jesus both minimized his biological family (the people looking for him), and he also claimed a different family—a chosen family. There are other places in the gospels where Jesus does this; I think “the twelve” are a kind of chosen family for Jesus, and the trio of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus seems to work like a chosen family as well. But here, Jesus drew a wide circle, claiming the gathered crowd as “my mother and my brothers,” indicating that something had shifted about the way he belonged in the world. He was no longer relying only on biological or genetic relationship, he was finding relationships in the world that he wanted to consciously cultivate and claim as family.

This is something that’s important for us to hear, whether we identity with the LGBTQia+ community or not, and whether our families of origin are important places of belonging for us or not. All of us get to choose the terms of our belonging, and all of us get to curate and cultivate our chosen families. For some of us, our biological families will be sufficient, but for others of us, there is life-giving power in doing what Jesus did and finding and building new kinds of families for ourselves. We too can make our identity about belonging, our kinship about community, and our family about love. We too, like Jesus, can reconfigure our sense of belonging to include the communities and people who matter to us in the world, and we can respect when others do the same. We too can thwart the norms that do not serve us, and we can start living our lives as if a larger truth were true. We too can choose and create the contours of our lives, so that like Jesus we can gesture to the people around us and declare, here is my family.