Nothing and no one should ever change.

Or, at least, that seems to be the position of some of our leading political figures and the institutions that influence our culture. We’re having a moment, nationally, of legislating the impossibility of change. The new presidential administration has moved quickly to insist that people’s genders assigned at birth must remain the gender assigned to them for the rest of their lives, blocking passports that don’t match birth certificates and moving to transfer trans persons into prisons matching their gender assigned at birth. In the administration’s eyes, no one could ever change. The NRA and the politicians it holds captive keep arguing that even as the technology of weapons changes, our gun laws should never change. Programs designed to get people to change their mind about how they treat others—often lumped together under the label of “diversity, equity, and inclusion”—are suddenly under attack in spaces from government to higher education to business. Climate change isn’t real, many people claim, because they don’t want it to be real. Pathogens never change, so there’s no need to fund research on emerging disease threats. I could go on.

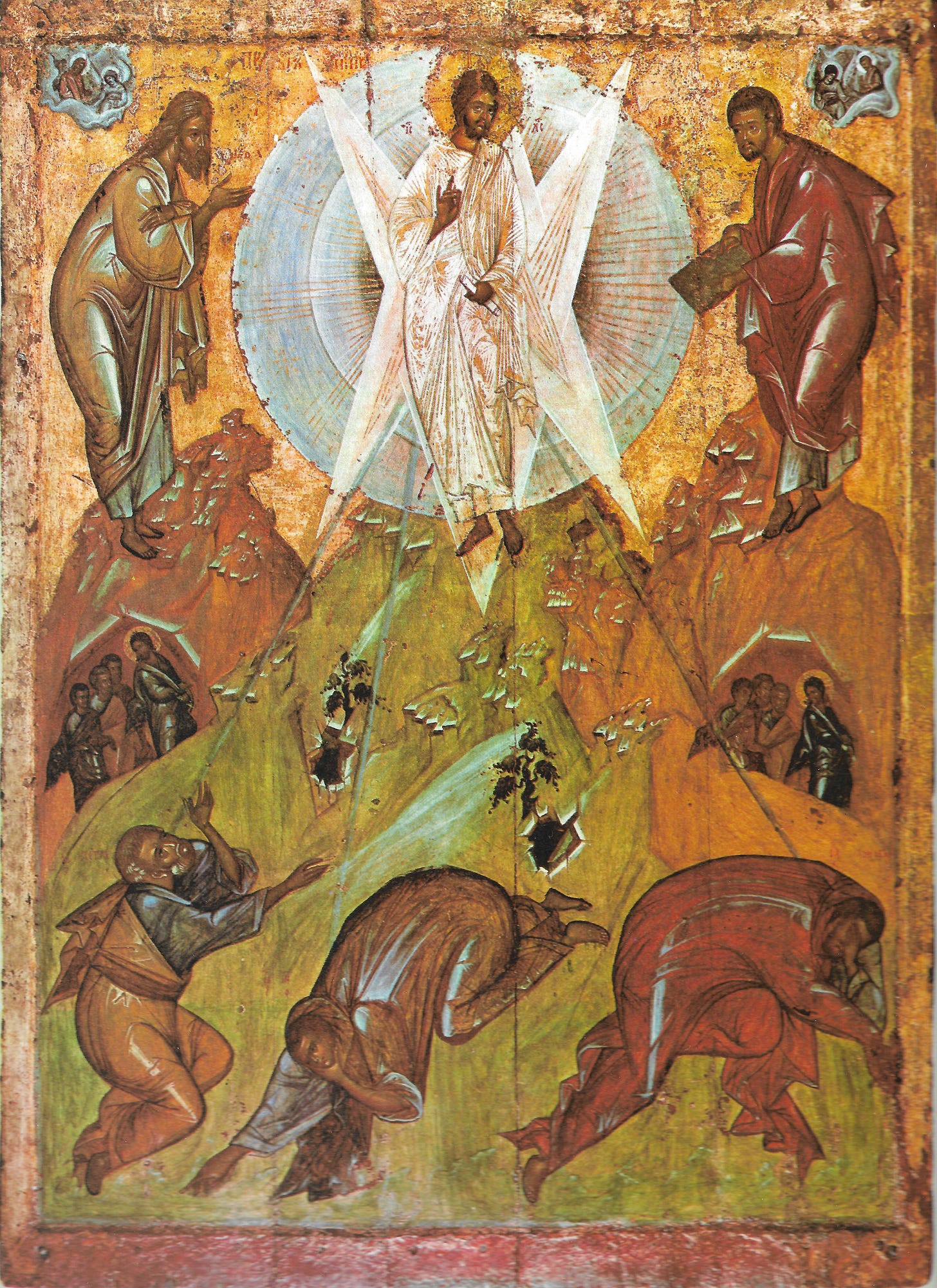

But the lectionary for March 2nd, which is Transfiguration Sunday, makes something very clear. Change is a theological good. Change, in fact, is central to the story of faith.

To make this point, the lectionary collects three passages, all centered on the theme of change. In Exodus 34:29-35, we find the story of Moses’ return from the top of Mount Sinai, and the ways he was changed by the encounter with God there. In 2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2, we find Paul reflecting on that same story from Exodus, and the ways people change (or don’t change) in response to God’s actions. And in Luke 9:28-36, the Gospel tells the story of Jesus’ own transformation—his transfiguration—at a pivotal point in his life.

The messages of these three passages converge on one important point: change is holy. Change is not only ok, and it is not only good. Change is what happens to us when we encounter God. When we meet the sacred, whether it happens on a mountaintop or in a time of crisis or in the discernment that happens in our hearts, we should expect to be changed, and we should learn to call that change holy. To deny the possibility of change is to deny the power of God.

It's shocking, to hold our national conversation about the rights of trans people up against the story of the Transfiguration, and see how different they are. The messages (and the executive orders) out of Washington have been clear: when people are born, they are already the people they will always be, with no possibility of change. Furthermore, the message goes, when people are born, they are born into the roles and patterns set for their genders long before they were alive. If you are born with a penis, you are a man, they say, and to be born a man is to inherit the traditional ways of manhood—no deviation allowed. And if you are born with a vagina, then you are a woman, and to be born a woman is to be born with certain capacities (childbirth, mothering, nurturing, vulnerability) and certain incapacities (serving in combat, ever being as strong as a man, making choices about your own reproduction) that cannot be changed. When they insist that trans people don’t exist, these politicians and right-wing trolls don’t only deny the possibilities of change to trans people. Boys are boys and girls are girls, they are saying, the world is a binary, and your gender is who you are, and whether you like it or not, you cannot stray from that. Gender essentialism doesn’t only attack the personhood of trans people, it attacks women who want to serve in the Marine Corps in a combat role and men who want to stay at home with the kids and anyone who fails to conform to gender norms in any way.

The Transfiguration, in contrast, is a celebration of change. The Transfiguration comes at a pivotal moment in the Gospel of Luke—somewhat literally. The ninth chapter of Luke is a turning point for the story, like a hinge in a door, where Jesus begins to move away from his Galilean ministry and toward Jerusalem and his ultimate fate. The turning of chapter 9 happens in two main moments. The first is this story of the Transfiguration, which tells us that Jesus’ appearance changed. “And while he was praying,” 9:29 says, “the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning.” And the second happens a couple dozen verses later, near the end of the chapter, in 9:51. “When the days drew near for him to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem.” The direction of Jesus’ face changes; he points himself in a new direction. The change in Jesus’ appearance is followed quickly by a change in his trajectory, both physically and in terms of his purpose. Once Jesus encounters God on the mountain, and his appearance is changed, he is able to embrace who he is truly meant to be.

We should notice that this change is oriented not only toward the future, but also toward the past. Even as Jesus is changed on the mountaintop, in the presence of God, and even as he begins to turn toward his newfound purpose and direction, the past comes alongside him. “Suddenly they saw two men, Moses and Elijah, talking to him,” because the Gospel wants us to understand that the change Jesus is undergoing is an extension of the past and an emanation from the past. The President and all the people doing his bidding—they want us to believe that a trans person’s transformation is a betrayal of the past, a rebellion against some pure and true origin. But talk to a trans person, and you’ll hear a story about how the future always emerges out of the past, not in opposition to it. I am not a trans person, so I cannot speak with full authority here, but every trans person I have ever heard from has said that their transition is a process of becoming fully who they have always been. The past comes alongside them and joins them in the present, so that they can be a whole person in the future. This is precisely what happens to Jesus in this story in Luke. Moses and Elijah appear just at the moment when Jesus’ appearance changes, and the past gives itself to the future. Jesus is able to set his face in a new direction because of the past, not in spite of it, and there was never any question of staying forever the way he had been born. Transformation—transfiguration—was a necessary starting point for the journey.

The mistake, in Luke 9, happens when we expect someone to live in the past forever. The mistake happens when we deny the possibility of change. Noticing the wonders and heroes of the past all around him, Peter suggests that they should all stay there forever, living out the way things used to be. “Master, it is good for us to be here,” Peter says to Jesus, so “let us set up three tents, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” Peter wants them all to freeze the moment and live that way indefinitely, never changing or moving onward. It would be enough, Peter thinks, to stop time and stay in the moment. It’s an understandable thing to want, if you’re Peter. There’s a simple-minded comfort that comes from insisting that nothing should ever change.

What happens next is so jarring that it almost feels like a line of text might be missing. It almost feels like a non sequitur, the transition from verse 33 to verse 35. As soon as Peter has suggested that they stop time and live in the past, a cloud surrounds them, and they hear a voice. “This is my Son,” the voice says, “my Chosen, listen to him!” And then they found themselves alone.

This feels like a non sequitur, like a strange jump in the story, but it’s not. What’s happening here is that at the moment when Peter is suggesting that Jesus should live in the past, God shows up to affirm the person Jesus was becoming and the future that belonged to him. It might feel like God’s declaration of divine parentage and affirmation of Jesus came out of nowhere, but it actually came as a rebuke to Peter and his backward-looking nostalgia. At the moment when Jesus claimed himself, God showed up to claim him too.

Change is holy, because it is the evidence that we have encountered God. It would have been easy for Jesus, for God, and for the Gospel of Luke to adopt Peter’s viewpoint, and to build some dwelling places and stay forever in the nostalgia of the past. But the Transfiguration makes it clear that Jesus could only become the person he was meant to be by embracing transformation and turning his face toward something new.

It's easy for us, too, to hunker down in a fantasy of the past, in a dwelling place made of our own chosen ignorance, and to insist that nothing should or could ever change. It would be easy to listen to the voices shouting confidently about other people’s stories, claiming that only we know who they really are, denying the possibility that anyone or anything could ever change.

But do not be deceived. The Transfiguration reminds us that change is holy, and that we will be transformed by our encounters with the divine. The Transfiguration reminds us that the signs of change will be made manifest in our appearance of our faces and even our clothing, and that most of all the signs of change will be evident in the way it leads us to our purpose—the way it leads us to be the people we have always been becoming. The Transfiguration reminds us that change is holy.

This may be one of my favorite of your stacks so far. The message is so clear that this is what we speak to and have the courage to know! The generations coming will thank you for marking these spaces and making the world safer. Sending you and Jessa big hugs and continued respect and gratitude!!!!

Amen.