I can’t remember, now, who organized it or how I heard about it. I can’t remember how I convinced my parents to let me go or whether I snuck around to go there, and I’m really not sure how we managed to pull it off without anyone calling the cops on us. I can’t even really remember who was there, aside from a handful of faces that still snap into focus in my mind. But I still remember how it felt—like a rare and wild kind of freedom.

It was the fall of 1995, and I was a senior in high school, just a couple of months shy of my eighteenth birthday. Someone at school started spreading the word: tonight we’re meeting at the elementary school to play capture the flag. The elementary school was not the one I had attended; this one was about ten miles away, in a very small town in the southwestern corner of the county. When I was maybe eleven, in the late 1980s, I had spent a summer in a day camp at that elementary school, becoming an all-world four-square player and riding home each day in the back seat of my cousin’s friend’s sister’s Ford Escort. But I had only been back a few times since, to play a few rec league soccer games on the fields out past the playground on the south side of the parking lot.

I drove up after dark to find a cluster of cars already there. It’s this scene more than any that sticks in my mind—the glorious sight of teenagers unsupervised, hanging out where they were not supposed to be, making their own way, by the light of an October moon. People were milling around, and a few were sitting on the hoods of their cars. Couples were huddling for warmth and I’m sure someone was sneaking drinks (though I never saw anyone do it). It was the days before cell phones, so we spent ten minutes comparing notes about who had said they were coming, who might show up late, who couldn’t come because they had to work. Someone was in charge, even if I can’t remember who it was. Someone must have been there, pacing back and forth, figuring out the teams.

The fields to the south of the school were modest; it was an elementary school after all. Beyond the playground was the baseball field, the same one where I once got two hits as a member of the Apex Electric in a single Little League game. Those were the only two hits I got in my two years of playing, and they were both off the same pitcher in the same game. It wasn’t the pitcher’s fault, because both of the hits were sheer luck. I had no talent for baseball, and no strength or coordination of any kind. It was my first-grade year, when I was (I still remember) fifty pounds and fifty inches tall—lanky, and impossibly thin. My strategy was to swing hard and fast at the pitches. The coaches offered advice about choking up on the bat, watching the ball, and widening my stance, and I nodded to show that I was listening, but none of it ever made any sense to me. I just swung, and that one day on the elementary school field I got two hits. I felt like a hero. One of the hits was a double, because I knew how to run.

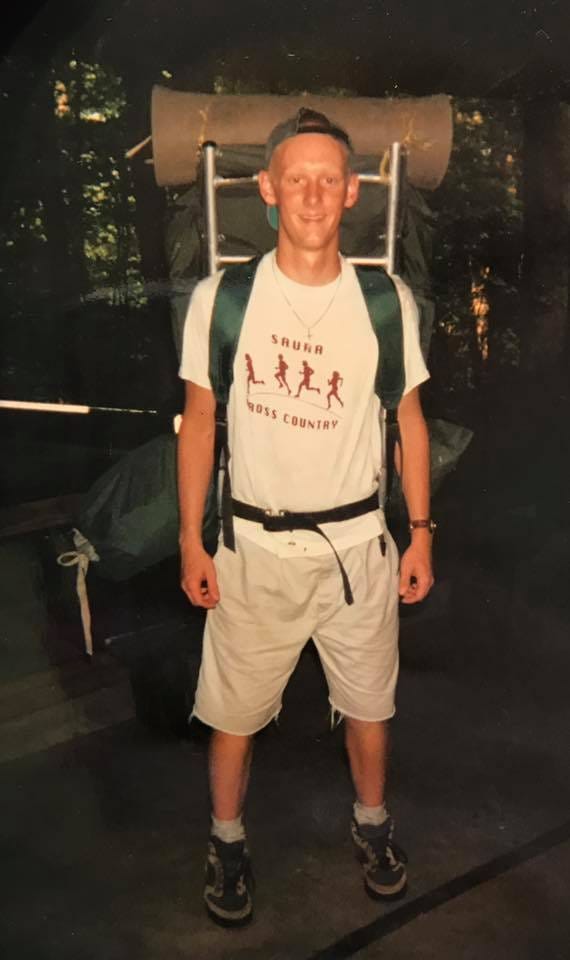

Seven years later I still knew how to run, even if that’s the only athletic thing I ever really knew how to do. In that senior year I was the third or fourth fastest runner on a third-place cross-country team. I was good enough, and the team was good enough, to be in the conversation, but I was nowhere near as fast as the two fastest runners, and the team was nowhere near good enough to sneak into the top two in the conference. It was a comfortable place to be, without a lot of expectations, and I loved everything about it, from the goof-off practices to the bus pulling up to McDonald’s after a race. I hated track season, with its asphalt circles and intense surveillance from the bleachers, but cross-country season was the perfect match for between my limited athletic abilities and my questionable dedication to improvement. The stakes were low, and the running was boundless.

That’s why I was there at the elementary school that night—for the running. It was a thing I did decently well, so a game of capture the flag sounded close to perfect. I’m sure that I had already been to cross-country practice that day, or maybe even a meet. I had probably already run five or seven miles of warmups and sprints, drills and distance. But when you’re seventeen the tank never really runs empty, and the idea of more running appealed to me. Someone had marked off the boundaries—the center line was from this post to that bench, or something like that. The teams were set, the flags planted, and the game was on, in the light of the moon.

I remember nothing about the game. I don’t know who was on my team, whether we won or lost, or how long we played. I remember running hard, but more than that I remember what it felt like to move across the wet grass in the dark, listening and waiting, turning and lingering in the shadows. I remember launching myself around and across obstacles in the way only a young person can do, and the feeling (since lost) of willing myself to go faster and having my body simply respond. I’m not sure whether or how often I tagged anyone, or got tagged. Who knows. It wasn’t really about that.

My friend Joe, who was also on the cross-country team, ran full-speed into a drainage pipe. I do remember that. He hit it with his shin, the bone right across the concrete lip that had been hidden in the dark. Joe was about as fast as I was, which is to say that he was quick but not the quickest, but he hit the drainage pipe hard. The leg was scraped and bleeding, and Joe was doubled up on the ground, and he didn’t want to speak for a long time. I think it took him weeks to get back to his running form, and he limped around school for longer than that. Any adult who happened by would have told us to stop playing capture the flag in the dark precisely because of the danger of the kind of thing that happened to Joe; we were there at night because we didn’t want to hear anything from anyone about the risks. So much of growing up is figuring out stuff just like that—learning for yourself where the limits are, how a thing can go wrong, and when to live with the consequences.

Joe was eventually fine, and I think we played capture the flag two or three nights that fall. It was not among the most rebellious things that most of us ever did; as far as I recall it was probably dangerous and possibly illegal, but innocent all the way through. When I think about what it means to feel free, to feel unbounded and open, I still sometimes think about that field and that moon, and what it was like to run in the dark. It’s rare to feel like that anymore, because the adult counsel lives in my head now, always ready to explain why things are risky and dangerous, and my mind now lives in a body that will never move that freely again. I miss that sense of possibility and transgressive freedom, and I recognize it in the teenagers I know, and I smile when I see it. I’m glad I got to feel it once, that sense of openness slipping through the dark, moving silent for the sake of moving fast.

Love this story and that feeling of freedom.

An enjoyable read.

“…willing myself to go faster and having my body simply respond.” I recall that feeling.