A programming note: This week’s lectionary post is a little on the short side, because I have been traveling all weekend and I haven’t had much time to write. But, I am now ensconced in a research and writing retreat, so I am anticipating posting a couple of times a week during December, hopefully a bit about what I’m writing and researching. Prepare yourself and your inboxes! On to the lectionary for this week….

One of the most fruitful ways to read a biblical text is to ask what it is anxious about. What does the text fuss over? What does it revisit again and again, and what does it insist on bringing to the reader’s attention? By noticing the text’s anxieties, we can learn something about the circumstances under which the text was written, and the kinds of things that might have preoccupied its authors. Sometimes this is closer to the surface, as in Paul’s letters, which are often transparent and obvious records of his anxieties. And sometimes the anxieties are buried deeper, under layers of textual bravado or everyday mundanity. But the anxieties are always there.

Two of the readings from the lectionary for the second Sunday of Advent bear the imprint of major anxieties of the early Christian movement: Jesus’ place in history, and Jesus’ status vis a vis John the Baptist. Actually, it would be more accurate to say that one of the texts (Mark 1:1-8) is anxious about these problems, and another (Isaiah 40:1-11) is included in the lectionary for this week because both Mark and the Christian tradition itself were and still are anxious about the same things. Mark 1:1-8 is working hard to show how Jesus fits within history—suggesting that Jesus’ place within history was a concern for his early followers. And one of the resources they used to address that concern was the prophetic tradition, which is quoted in Mark and cited in the lectionary in the Isaiah text—but not in the way you think.

The Mark text is from the very beginning of what might have been the earliest canonical gospel; Mark’s gospel was probably written within 35 or 40 years of Jesus’ death. And even in these opening verses of that early gospel, you can see the author (and the tradition) wrestling with Jesus’ identity. The text calls Jesus “Christ,” which means “anointed one,” and also “Son of God,” right off the bat. These are theological titles, meant to guide readers as they encounter the story of Jesus. The gospel wants to make sure you know who this Jesus is, even as it begins to tell his story. But in the very next verses, the second and third ones of the gospel, the text quotes Isaiah—or, at least, it says it’s quoting Isaiah. If you go look at Isaiah—not just the passage from 40:1-11 that is included in this week’s lectionary, but the whole book—you’ll find that the thing Mark says Isaiah says, Isaiah does not actually say. Instead, you’ll find the things that Mark is quoting in verses 2 and 3 in Malachi and Exodus.

Scholars argue over whether the author of Mark was being duplicitous or just forgetful by saying these passages were from Isaiah when they actually weren’t. For my money, I think it was probably a mistake. Remember, most people didn’t have access to written biblical texts, so many New Testament citations of Hebrew Bible texts are from memory—even the ones Jesus quotes himself. And at other times, the citations differ from the versions we have today, suggesting that the people quoting them were quoting from memory, quoting a translation from a different language (like Greek) than the Hebrew that lies behind our modern Hebrew Bible translations, or fiddling with the citation to make it fit the context better. I don’t think any of those options should scandalize us, because those kinds of mistakes are only scandalous if you have a view of scripture in which it cannot contain errors or even problems. But that’s a modern view. Ancient people (including Jesus) clearly didn’t hold that view of scripture; they seemed to understand scripture as living, malleable, and subject to the effects of memory. So when Mark says it’s quoting Isaiah when it’s actually quoting Malachi, that gives us a clue about how Mark is using scripture—not as an encyclopedia or compendium of theological knowledge to be drawn upon but never added to, but as a set of tools for building new theologies.

To see this kind of building in action, look at the way not-Isaiah (Exodus and Malachi) are used in Mark 1:2-3. Why are these citations here? Mark has put them here to address a couple of anxieties that he had (and that the Christian tradition had), mentioned above. The first anxiety was what to do with John the Baptist, who seemed to have been kind of a big deal in his own right. The second anxiety was Jesus’ place in history—how people were supposed to understand Jesus’ appearance in the world in the context of the long history of Israel and its God.

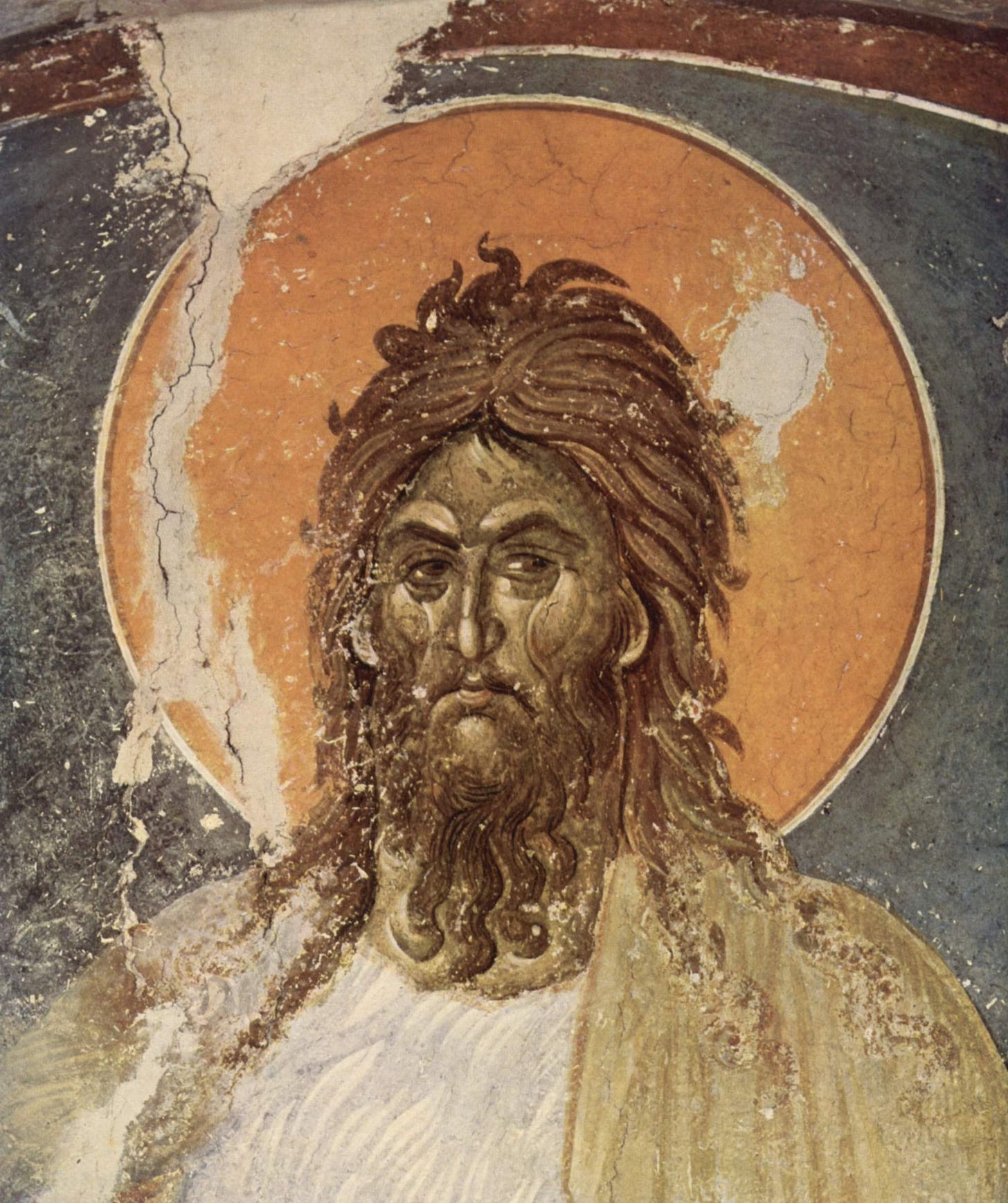

The first problem, John the Baptist, seemed to create a lot of anxiety for Mark and other early followers of Jesus. Notice how often the gospels go out of their way to subordinate John to Jesus, and how awkward they are when they interact. Whenever John and Jesus appear together in the text of the gospels, there almost has to be a moment when John makes a big deal about being inferior to Jesus, or when the narrator makes sure the reader knows who’s more important. In this passage from Mark, it’s the latter. By quoting Hebrew scripture to apply to John, Mark makes John the forerunner, the messenger sent ahead of time to proclaim the coming of the more important person. John’s role is important, for sure, but it’s also by definition a supporting role. So, the citation from Malachi-not-Isaiah serves to let the reader know that John was lesser than Jesus.

But that’s not all it’s doing. Even as it’s using the citation to establish Jesus’ importance over John, Mark is also arguing for a very specific role for Jesus within the stories of ancient Israel. By calling Jesus the “anointed one” and the “Son of God,” and then going on to quote scripture about it, Mark is making a claim that Jesus is the one who was foreseen by the prophets—whichever ones he’s actually quoting. Mark is using scripture as a building block to construct an identity for Jesus, and that identity is messianic.

Mark, and the other gospels, fuss over both of these things—John’s relative status, and Jesus’ place in the history of Israel. They visit and revisit these things again and again, working hard to make sure the reader understands the right things about them. That tells us that these things were a source of anxiety for Mark and for the other gospel writers, worth spilling some ink over in order to get it right. In the opening verses of Mark, the gospel writer is very eager to seize the opportunity to let the reader know how they should think about both of these things. Jesus is superior to John, but John’s presence is important because he heralds the coming of an important, long-awaited figure within Israel’s history. Mark finds a way to do all of that in a tidy few verses.